Streaming a video is now a widespread activity for many of us. But, what are…

The post What Is the Carbon Footprint of Video Streaming? appeared first on Earth911.

Streaming a video is now a widespread activity for many of us. But, what are…

The post What Is the Carbon Footprint of Video Streaming? appeared first on Earth911.

For nearly a decade, Holly Alpine (née Beale) loved working at Microsoft. Shortly after finishing college, in July 2014, she landed a job there as a technical account manager. Less than four years later, Alpine was leading a program that invests in environmental projects in the communities where Microsoft’s data centers are located. She was also helping organize a worker-led sustainability group called the Sustainability Connected Community, which would grow to nearly 10,000 Microsoft employees worldwide by late 2023.

But at the end of last year, Alpine reached a painful decision: She could no longer ethically work at Microsoft. On January 24, 2024, Alpine sent an email to Microsoft president Brad Smith, CEO Satya Nadella, and several other senior company officials, letting them know why.

Writing on behalf of herself and a colleague who resigned at the same time, Alpine told the tech giant’s top brass that the two were quitting in “no small part” due to Microsoft’s work for the fossil fuel industry aimed at automating and accelerating oil extraction.

“This work to maximize oil production with our technology is negating all of our good work, extending the age of fossil fuels, and enabling untold emissions,” Alpine wrote in the email. “We are both deeply saddened to be so let down by a company we loved so much.” (Alpine’s colleague asked Grist not to identify them, citing concerns over how it might affect their future employment prospects in the tech industry.)

Alpine’s blunt resignation letter didn’t come out of nowhere. For years, she was one of the faces of an internal, employee-led effort to raise ethical concerns about Microsoft’s work helping oil and gas producers boost their profits by providing them with cloud computing resources and AI software tools. Former Microsoft employees and sources familiar with tech industry advocacy say that, broadly speaking, employee pressure has had an enormous impact on sustainability at Microsoft, encouraging it to announce industry-leading climate goals in 2020 and support key federal climate policies. But convincing the world’s most valuable company to forgo lucrative oil industry contracts proved far more difficult. Eventually, Alpine decided speaking up internally wasn’t enough.

This spring, Alpine spoke with Grist for her first on-the-record interview describing her experience advocating for change inside Microsoft. By speaking out publicly despite her concerns about legal risks, Alpine hopes to place additional pressure on her former employer to address the emissions it is enabling through technology partnerships with fossil fuel companies. Alpine’s account, along with those of other former Microsoft employees, as well as internal documents current and former employees shared with Grist, offer a rare glimpse into how tech industry workers are applying behind-the-scenes pressure to hold their bosses accountable on climate change.

“My resignation was driven in part by the realization that the tech industry, including Microsoft, is increasing the profitability and competitiveness of these fossil fuel giants and perpetuating their existence when they should be phased out,” Alpine told Grist. “It became apparent after years of internal efforts … that Microsoft was unwilling to enact meaningful change.”

A Microsoft spokesperson told Grist that the company’s employees are “core to our sustainability mission” and that executives engage with employee groups, like the Sustainability Connected Community that Alpine helped establish, “on a regular basis as part of an ongoing dialog.”

“The energy transition is complex and requires moving forward in a principled manner. We believe that technology has an important role to play in helping the industry decarbonize, and that requires balancing the energy needs and industry practices of today while inventing and deploying those of tomorrow,” the spokesperson added. “And we continually monitor our emissions, accelerate progress while increasing our use of clean energy to power data centers, purchasing renewable energy and other efforts to meet our sustainability goals of being carbon negative, water positive, and zero-waste by 2030.”

It’s true that Microsoft is taking numerous steps to address the sustainability of its own operations. But for years, the company has also furnished fossil fuel giants with cloud computing services and specialized software tools powered by machine learning and AI in order to streamline and automate their operations. These digital technologies help companies discover oil faster, squeeze more from existing wells, and boost productivity across their operations in order to stay cost competitive in an age of cheap renewable energy. The digital services market for oil and gas is “immense,” as a 2020 report by oil industry analysts at Barclays put it, with the potential to unlock $150 billion in yearly savings for producers.

Over the past seven years, Microsoft has announced dozens of new deals with oil and gas producers and oil field services companies, many explicitly aimed at unlocking new reserves, increasing production, and driving up oil industry profits.

In 2017, Alpine and former Microsoft employee Drew Wilkinson came together to organize a small group of workers who shared a passion for sustainability and wanted to make positive changes at Microsoft. In early 2018, that group was folded into the company’s formal Connected Communities program, which provides employees with support and resources to organize volunteer communities based on shared interests. The mission of the Sustainability Connected Community — to make sustainability part of everybody’s job at Microsoft — resonated with workers around the world, and the group quickly grew to several thousand members.

In the group’s first few years, tech companies’ oil and gas contracts became a focal point for climate-concerned workers across the tech industry. As they organized and began pressuring their bosses to take action on climate, news outlets started calling out Big Tech for creating AI technology aimed at accelerating oil production.

At an employee town hall in September 2019, a Microsoft worker asked Nadella, the company’s CEO, if he believed that helping oil companies extract more fossil fuels was an ethical use of the company’s technology. Nadella responded by stressing that fossil fuel companies are actively investing in the energy transition, according to a meeting transcript that was manually recorded by employees present at the time. Nadella’s response implied that by helping oil companies be more productive and achieve cost savings, Microsoft was enabling them to put more resources into emissions-reducing innovations.

“To me his answer was borderline gaslighting,” Wilkinson told Grist. “Those of us in the sustainability community were like, ‘The work you’re doing is not to help them transition. The work you’re doing is to help them find and extract and burn more oil.’”

As concerns over the company’s fossil fuel work mounted, Microsoft was gearing up to make a big sustainability announcement. In January 2020, the company pledged to become “carbon negative” by 2030, meaning that in 10 years, the tech giant would pull more carbon out of the air than it emitted on an annual basis. The news generated a wave of positive media attention and was met with cheers from the Sustainability Connected Community, Wilkinson said.

“The initial reaction was like, ‘Holy sh–t, this is awesome,’” Wilkinson told Grist. “All this pressure we put on the company” — not just around the oil contracts, but sustainability more broadly — “worked.”

The group’s concerns over Microsoft’s fossil fuel business “died down” for a while, according to Wilkinson: “Those of us who had been organizing on it back in 2019 were like, ‘Let’s wait and see what they do. Let’s give them a chance.’”

For nearly two years, employees watched and waited. Following its carbon negative announcement, Microsoft quickly expanded its internal carbon tax, which charges the company’s business groups a fee for the carbon they emit via electricity use, employee travel, and more. It also invested in new technologies like direct air capture and purchased carbon removal contracts from dozens of projects worldwide. But Microsoft’s work with the oil industry continued unabated, with the company announcing a slew of new partnerships in 2020 and 2021 aimed at cutting fossil fuel producers’ costs and boosting production.

For Alpine, Wilkinson, and other employees, the incongruity between Microsoft’s climate goals and its efforts to enable oil extraction was too big to ignore. In late 2021, a small group of employees involved in the Sustainability Connected Community came together to craft a memo for Microsoft’s leadership calling attention to the climate impact of the company’s fossil fuel business. By customizing its cloud computing technology for oil and gas companies, Microsoft was “enabling far more emissions than we offset or remove,” employees asserted — yet those indirect emissions were not included in the company’s internal carbon accounting. The employees calculated that a single deal with Exxon Mobil to expand production in Texas and New Mexico by up to 50,000 barrels per day could enable carbon emissions adding up to 640 percent of the company’s carbon removal target for 2021.

“We believe we must hold ourselves accountable for the enabled emissions of our technology,” reads the memo, a copy of which was shared with Grist. “Our principled approach and leadership can — and should — set an industry standard.”

The memo goes on to outline more than a dozen recommendations for the company, including advocating for policies that align with 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) of warming, measuring the emissions increases (or reductions) enabled by Microsoft’s technology, and ceasing to develop custom software tools aimed at increasing oil extraction.

In December 2021, Alpine, along with two other employees who asked Grist not to identify them, held a meeting with Smith and Lucas Joppa, who was then Microsoft’s chief environmental officer, to discuss the memo and present their recommendations. The meeting felt “really positive,” Alpine told Grist, adding that Smith expressed agreement with most of the employees’ recommendations and even appeared surprised that one of them — adding environmental impacts to Microsoft’s internal principles governing the responsible use of AI — hadn’t already been implemented. Smith, Alpine said, even offered to assemble a small team to further explore the concept of environmentally responsible AI principles. A former Microsoft employee familiar with the company’s responsible AI standards told Grist the idea was investigated but never went anywhere; the company’s responsible AI principles still do not include sustainability.

Microsoft and Joppa declined to comment on the meeting.

Alpine told Grist she left the meeting “hopeful that things would change.” And several months later, in March 2022, Microsoft issued a blog post outlining a series of principles that would guide its future work with the energy industry. The so-called energy principles included expanding work on initiatives focused on low and zero-carbon energy and helping energy customers develop “effective net-zero commitments.” Perhaps most significantly, the principles stated that Microsoft would only develop specialized tools for oil and gas extraction for companies that had agreed to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 or sooner.

“We were really excited when [the principles] were first published,” Alpine told Grist. “They were published, we were told, in part because of our advocacy, which felt really good.”

But the more Alpine and others asked questions about the principles, the more they felt let down. Microsoft’s pledge to only develop custom fossil fuel extraction technologies for companies with a net-zero target only covered the emissions associated with producing the fuels, known as Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions. Oil and gas companies weren’t being asked to zero out the emissions associated with burning fossil fuels, known as Scope 3 emissions, which can represent upwards of 85 percent of their total emissions.

What’s more, oil companies simply had to put forth a net-zero target. Microsoft wasn’t requiring them to do anything to show they were on track to meet it.

“Requiring a net-zero target only for Scope 1 and 2 emissions brushes aside the vast majority of the problem, which is the emissions that result from burning the fossil fuel companies’ products,” said Bill Weihl, founder of the nonprofit advocacy group ClimateVoice and a former sustainability director at Facebook and Google. “And a 2050 target, with no intermediate targets that would demonstrate a real commitment to shifting toward clean energy, is essentially meaningless.” Microsoft declined to comment on these concerns.

In November 2022, the Sustainability Connected Community held a call with Darryl Willis, Microsoft’s corporate vice president of energy, to discuss the principles. According to a meeting transcript generated by Microsoft Teams, employees peppered Willis with questions about what the principles meant and how Microsoft was implementing them, including which standards Microsoft would use to judge energy companies’ net-zero pledges, whether Microsoft was bringing up Scope 3 emissions in conversations with energy industry clients, and whether Microsoft had a plan to transition its energy division revenue away from fossil fuels.

Willis acknowledged that there was “a lack of standards” around Microsoft’s net-zero requirement, and that including emissions from the burning of fossil fuels in companies’ net-zero targets was “going to be a journey.”

“It’s hard, it’s big, it’s complicated,” Willis told employees on the call, according to the transcript. “But I think it’s not unrecognized as a necessity.”

On the call, Willis committed to providing employees with updates on net-zero requirements as Microsoft continued to implement the principles. He also committed to providing a breakdown of the energy division’s revenue across six different sectors, from oil and gas extraction to low- or zero-carbon energy, as well as an analysis of personnel resources assigned to extractive industries versus renewable energy. Finally, Willis agreed to share a plan for how Microsoft’s energy division would transition its revenue toward low-carbon energy.

Alpine says she held several additional meetings with senior energy division and sustainability officials at Microsoft over the following year, and that Willis joined the Sustainability Connected Community for another call in November 2023. But the promised updates and analyses never materialized. At a December 2023 meeting with energy executives, Alpine says she was told that Microsoft was not responsible for defining net-zero for their customers, as there’s no global standard. (Microsoft declined to share any additional information with Grist concerning its net-zero standards for energy sector clients or any of the other commitments Willis made to employees in 2022.)

A few weeks later, Alpine came across a LinkedIn blog post Microsoft technical architect Azam Zaidi had written in April 2023 about the company’s work on oil and gas industry automation. Microsoft’s cloud services division, Azure, Zaidi asserted, was “at the heart” of the fossil fuel industry’s digital transformation,“enabling faster and more accurate decision-making and unlocking previously inaccessible reserves.”

“With Azure,” Zaidi concluded, “the future of oil and gas exploration and production is brighter than ever.”

“That was really a nail in the coffin for me,” Alpine said.

In her January resignation email to Smith, Alpine quoted Zaidi’s post directly. “Facilitating a ‘future of oil and gas’ that ‘is brighter than ever’ goes against everything that we stand for, and everything we thought this company stands for as well,” Alpine wrote.

Melanie Nakagawa, Microsoft’s chief sustainability officer, responded to Alpine the next day, thanking her for her “continued advocacy for sustainability.” Microsoft, Nakagawa wrote, is continuing to “uphold and adhere” to the energy principles, which the Sustainability Connected Community “had a role in shaping.”

Weihl of ClimateVoice says it’s important to recognize that Microsoft employees “have been very effective internally on several fronts,” including encouraging the company to publicly voice its support for the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, which earmarked hundreds of billions of federal dollars toward clean energy. Last fall, Weihl said, employees at Microsoft launched an internal campaign targeting the company’s membership in trade associations that oppose climate policy, like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Earlier this year Microsoft released an audit of its trade associations showing their alignment (or lack thereof) on climate policy, which Weihl called “a big step toward accountability.”

Wilkinson, who started his own climate consulting business after he was laid off from Microsoft in early 2023, has maintained contact with many former colleagues in the Sustainability Connected Community. When it comes to addressing the emissions Microsoft enables within the fossil fuel industry, “the work is continuing,” he said.

Alpine isn’t sure what’s next for her career-wise, but she’s considering focusing on coalition-building around the emissions that tech corporations enable, or sustainable food production. In the meantime, she’s keeping the heat on Microsoft by speaking out publicly about her time there.

Weihl is optimistic about what Microsoft employees — and former employees — can do if they continue to raise a ruckus.

“The energy principles open a door,” he said. “So do the commitments Willis made. Employee pressure made that happen. It’s now up to employees … to keep the pressure on and make sure those principles and those commitments aren’t just window dressing.”

Correction: This story originally misidentified the structure of Holly Alpine’s work leading a program that invests in environmental projects in the communities where Microsoft’s data centers are located.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Microsoft employees spent years fighting the tech giant’s oil ties. Now, they’re speaking out. on May 8, 2024.

A quarter of the annual greenhouse gas emissions in the United States come from electricity generation. The biggest polluters in the sector are the country’s coal-fired power plants — decades-old facilities that emit enormous quantities of carbon dioxide and other pollutants into the air. Federal regulators and policymakers have spent years coming up with a plan for minimizing emissions from fossil fuel-run power stations. The Environmental Protection Agency finally unveiled the results of that work last week: a historic suite of rules that aim to prevent 1.4 billion metric tons of carbon pollution by 2047, the equivalent of annual emissions from 328 million gas cars.

The new rules were finalized under multiple laws, including the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act. In addition to cutting carbon emissions, they are expected to vastly reduce air, water, and soil pollution from fossil fuel-fired power plants by preventing toxic discharge into rivers and streams, better controlling coal ash pollution, and reducing toxic mercury emissions.

Of the four new rules, one in particular sets a new precedent by being the first to require the implementation of carbon capture and storage, or CCS, in order for certain existing plants to continue operating. Some of the facilities that fall under the rules are the more than 200 coal-fired power plants across the country that collectively account for more than half of the energy sector’s carbon emissions. Per the regulations, the companies operating these facilities have three options: they can capture 90 percent of their emissions and keep running past 2039, capture a smaller share of emissions and close by 2039, or continue operating normally and retire by 2032.

Carbon capture and storage is a complex, multi-site process that involves trapping the gas at the point of emission and piping it underground to a well where it is injected for long-term storage. And so some climate advocates fear that the rule will only prolong the lives of power plants that run on fossil fuels.

Other critics of the EPA’s rules doubt the technology’s effectiveness, and point out that it has never been deployed on a commercial scale. Despite the hundreds of millions in tax incentives that the Biden Administration allocated to spur the development of CCS, there are currently no operations in the US that capture a substantial portion of a facility’s emissions. The fossil fuel giant Occidental Petroleum quietly abandoned its largest CCS facility in Pecos County, Texas, last October, selling it for a fraction of its construction cost. Elsewhere, Chevron’s massive operation on Barrow Island off the coast of Western Australia is successfully capturing carbon, but challenges in the underground storage system has led it to only store 1.6 million tons per year, under half its capacity.

Still, some other climate advocates say the rule fits well into their overall strategy: Capturing and storing carbon is such an expensive endeavor that some of the country’s oldest and biggest emitters, they hope, will choose to shut down rather than operate under the new rule.

“This is a regulation that on its face appears to be mostly about CCS,” said Emily Grubert, a civil engineer and environmental sociologist at the University of Notre Dame. But Grubert believes that the rule can be harnessed for other ends: “The goal of the climate movement is for it to be about plant retirement.”

Grubert told Grist that it is unlikely many of the operators of these plants will elect to retrofit their facilities with CCS, since adopting the technology can cost companies over $1 billion.

“I don’t want to see carbon capture put on the coal plants. The U.S. coal fleet is very old,” Grubert told Grist. “When you talk about putting multibillion-dollar investments on these plants, that almost certainly guarantees that they will stay open longer than they would have otherwise.”

Advocates who live in communities near CCS infrastructure along the Gulf Coast in Texas and Louisiana applauded some aspects of the new rule, but worried about the safety of the new technology. Capturing and storing carbon involves a complex network of industrial equipment, underground pipelines, and injection wells, each of which has their respective risks. When a pipeline carrying carbon dioxide ruptured in Mississippi in February 2020, dozens of people were rushed to the hospital after experiencing shortness of breath. A similar incident occurred with an Exxon Mobil-owned pipeline in southwest Louisiana last month. With the EPA’s recent decision to grant industry-friendly Louisiana the authority to approve new carbon dioxide wells, advocates worry that the majority-Black communities that live alongside much of the South’s fossil fuel infrastructure will have yet another pollution hazard in their midst.

“We’re looking at a perfect storm,” said Beverly Wright, the executive director of the New Orleans-based Deep South Center for Environmental Justice. “You have this new shiny object that’s gonna solve all our problems by pumping the carbon into the ground. But whose ground?”

Existing coal plants have until 2032 to implement CCS and reduce their carbon emissions by 90 percent or shut down. Some politicians have indicated their determination to fight these requirements and keep the country’s coal fleet running without emissions-reducing technology. When the rules were initially proposed last year, a group of Republican attorneys general led by Patrick Morrisey of West Virginia wrote EPA Administrator Michael Regan a letter saying the regulations would “kill jobs, raise energy prices, and hurt energy reliability.” Last week, Morrisey threatened to challenge the EPA’s finalized decision in court. Separately, Shelley Moore Capito, a Republican senator from West Virginia, said she planned to draft a resolution opposing the rules. But beyond the potential legal and congressional challenges, CCS technology will have to develop substantially over the next decade to be used on a commercial scale.

Nonetheless, Grubert told Grist that it’s important not to discount CCS entirely. While solar and wind farms can replace the country’s rundown coal plants, there are currently few alternatives to clean up major emitters like cement manufacturing plants. In her ideal scenario, the new EPA rules will encourage the coal plants to go offline within the next decade, while spurring investment in other sectors where capturing carbon might be necessary in the interim, to minimize climate warming emissions.

“Begrudgingly, I think we do need to be able to” implement some CCS, Grubert said. “Having a regulatory framework and a regulatory environment that ensures that carbon storage is safe and well communicated to people is a good idea.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline One way or another, new EPA rules will stop pollution from coal-fired emissions on May 8, 2024.

Every email you send has a home. Every uploaded file, web search, and social media post does, too. In massive buildings erected from miles of concrete, stacked servers hum with the electricity required to process and store every byte of information that modern lives rely on.

In recent years, these data centers have been rapidly expanding in the United States. But the gargantuan facilities do more than keep cloud servers running — they also guzzle absurd amounts of water to run cooling systems that protect their components from overheating. Now, as artificial intelligence applications become ubiquitous, they’re using more water than ever.

Northern Virginia is the data center capital of the globe, where more than 300 facilities process nearly 70 percent of the world’s digital information, a job that requires ever more electricity. A utility that serves the area, Dominion Energy, announced during a May 2 earnings call that the industry’s demand for electricity had more than doubled in recent years. The week before that call, Google announced a billion-dollar expansion of three Virginia facilities, following a $35 billion investment by Amazon Web Services in the same area last year. State lawmakers and environmental groups have begun worrying about what this industry boom means for the area’s supply of water.

“Some of these data centers will use resources equivalent to a small city for energy and water,” said Ann Bennett, chair of data center issues in the Sierra Club’s Virginia chapter. “They are being built on a scale that we just haven’t seen in the past.”

Large data centers are resource hogs, using as much as 5 million gallons of water a day. Big companies, such as Google, Microsoft, and Meta, have faced public backlash for sucking up groundwater in regions plagued by droughts, such as in Arizona. But warming temperatures and more heat waves are driving increased water scarcity even in states that are not used to shortages. Last summer and fall, Virginia suffered a monthslong drought. The worst of the dry spell was in the same watershed as “data center alley,” part of Loudoun County where thousands of technology companies make use of the greatest concentration of data centers in the world, in an area the size of 100,000 football fields.

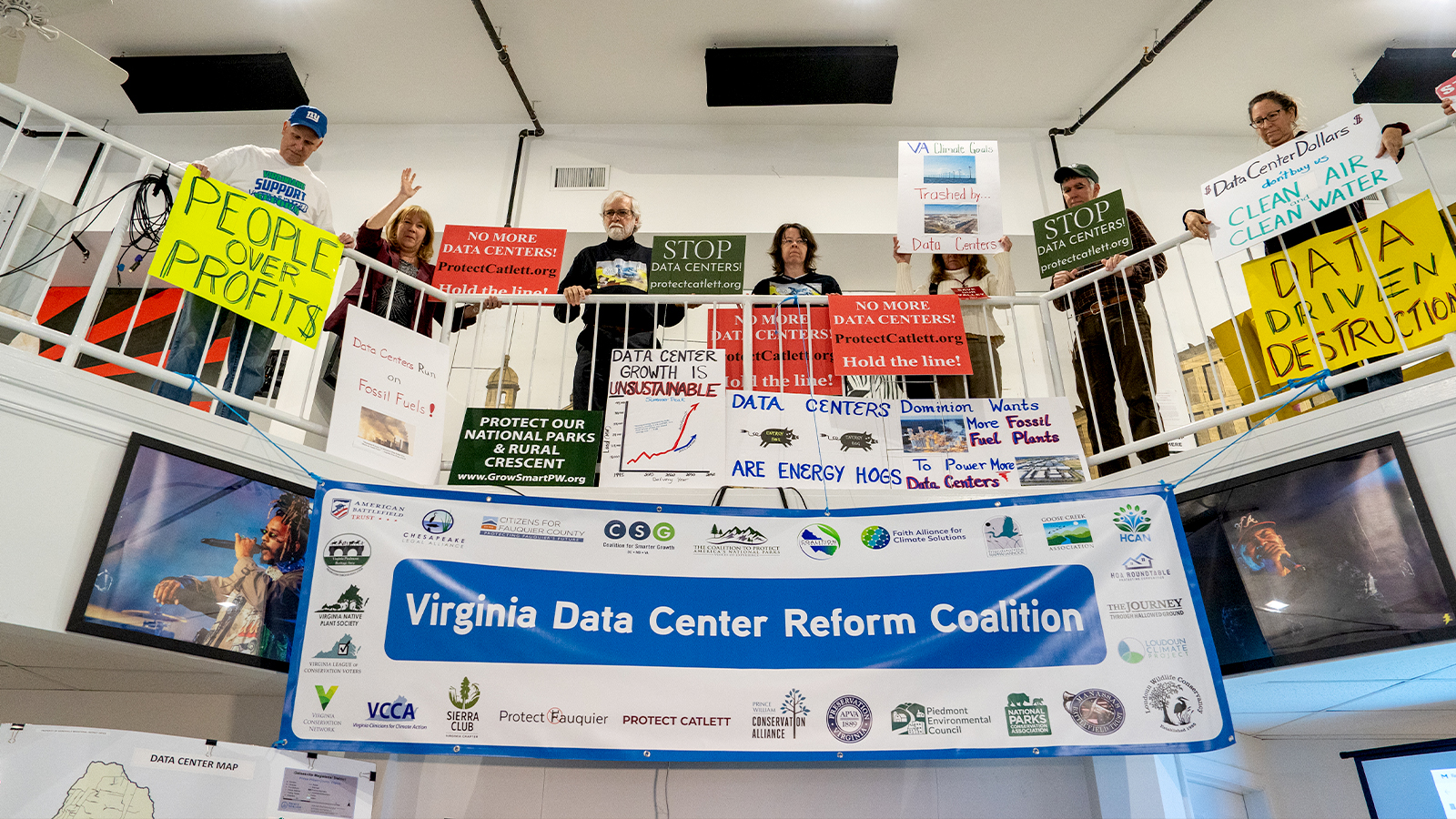

“I think as we look towards climate change and drought, somebody has to start asking these questions about how that impacts water supply and future increasing need,” said Kyle Hart, a program manager of the National Parks Conservation Association in Alexandria, one of the groups involved in the recently formed Virginia Data Center Reform Coalition. Many environmental advocates say that because companies often don’t divulge details about their water use, calling attention to these issues is a challenge.

Data centers rank among the top 10 water-consuming industries in the United States, according to a 2021 study from Virginia Tech that looked at their environmental cost. And the next generation of technology will only make these facilities thirstier, as servers that run AI algorithms generate more heat. Compared with traditional computing, the average neural network needs six times more kilowatts per rack. And AI scales exponentially: Large-scale algorithms, used by the likes of Google, Amazon, and Microsoft, consume at least 100 times more computing power and process millions of more data points than simpler kinds of machine learning.

To crunch all those bytes, tech giants are seeking out more data centers. Information about how many servers are being used for AI applications is not publicly available, but according to polling by Forbes, more than half of businesses use AI in some capacity. Amazon Web Services, which has 85 data centers in northern Virginia alone, offers hundreds of AI applications to its clients.

In Virginia, the scramble to stake land for data centers has some residents concerned. In December, local officials in Prince William County approved a $40 billion land-development project that will turn the county into the world’s largest data center hub. The public debate took 27 hours and drew nearly 400 citizens who raised questions about water availability, effect on the grid, and noise pollution.

Dozens of climate advocacy and historical preservation organizations formed the Virginia Data Center Reform Coalition at the end of last year over concerns that data centers were being built without prior understanding of the consequences. Julie Bolthouse, director of land use at Piedmont Environmental Council, one of the members of the coalition, says without more information about the resources these facilities consume, it’s difficult to draw a line from data centers to water issues. “We just don’t know. And that’s the biggest problem: We need more transparency around this industry,” she said. “And yet we’re approving them because of the promise of increased revenue.”

“Data centers are really secretive about their operational details,” said Md Abu Bakar Siddik, an engineering doctoral student who co-authored the Virginia Tech study. In 2022, Google became the first company to publicize its data centers’ water use following a lengthy legal battle in The Dalles, Oregon. While a handful of other tech giants, like Microsoft, have followed suit, most companies remain tight-lipped.

Ben Townsend, head of infrastructure and sustainability at Google, says the tech giant has some of the most sustainable data centers in the industry. And if a drought hit the area, Townsend said that Google would work with the local utilities “well in advance to understand what behaviors need to be taken to best support the watershed.”

Last month, Bolthouse learned from a Freedom of Information Act request that data centers serviced by the Loudoun water utility had increased their use of drinking water by more than 250 percent between 2019 and 2023. The documents also showed that water usage peaked during the summer months when the risk of drought is the highest.

Recycled water is being used in some data centers, such as in a Google facility in Georgia. But Siddik says fresh water is usually necessary to keep cooling systems running smoothly.

Shaolei Ren, an engineering professor at University of California, Riverside, said that instead of returning the water to a city wastewater system, like the one connected to your drains at home, many data centers use cooling methods that rely on evaporation. A study he co-authored last year found that just training Open AI’s flagship product, GPT-3, might have directly evaporated more than 700,000 liters of clean fresh water. “Whether the water is recycled, saline, or fresh water, afterwards the water is just gone,” Ren said.

Some Virginia lawmakers have tried to hold companies accountable for their impact on the environment. In February, Josh Thomas, a Democrat in the Virginia House of Delegates, introduced several data center reform bills, including one that would require counties to conduct water studies before approving new developments. Although the legislation made it through the Virginia House in February, the Senate vote was eventually postponed until 2025, effectively killing it. According to Thomas, industry groups lobbied against the bill. By the time he reintroduces it during next year’s legislative session, lawmakers and the Data Center Reform Coalition expect an environmental impact study, commissioned by Virginia, will be complete.

“I think it’s very fair to paint a picture of a very obstinate industry that is opposed to any type of check on its growth,” Thomas said. “If we don’t do something quickly, there may be a tipping point where anything we do might not have an impact.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misidentified the location of a data center in which Google is using recycled water. This post has also been updated to clarify that Google disclosed its data centers’ water use across the U.S. in 2022, not in one location.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline The surging demand for data is guzzling Virginia’s water on May 8, 2024.

It’s no secret that humans produce and use far too much plastic. The more than 400 million tons generated each year is polluting our planet and choking our oceans.

The plastic crisis is so great that 80 percent of marine debris — from microplastics to fishing gear — is made from plastics, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

A new initiative, SailGP vs Plastic, aims to combat the climate crisis by raising awareness through a group of individuals who have a special relationship with the ocean — the sailing community.

Launched by Parley for the Oceans and the Australian SailGP Team, the campaign aims to fight plastic pollution and its connection to climate change through a free, centralized platform designed to educate, engage and inspire action.

“Together with Parley, we’re aiming to start an impactful movement within the SailGP community and among ocean lovers nationwide, to advocate for a low-carbon future, promote sustainable solutions, and ultimately protect the environment,” said Tom Slingsby, Australia Team CEO, in a press release from Parley for the Oceans and SailGP. “While it’s about raising awareness of the current climate challenges both locally and globally, we also want to inspire real action against plastic pollution and encourage eco-friendly practices, ensuring our oceans thrive for years to come.”

The platform, developed by Parley experts and educators, offers educational materials along with information about community and collaborative activities like local beach clean-ups. On the site, visitors have the opportunity to discuss issues and solutions related to climate change while learning more about them.

“Together, Parley and the Australia Team hope the platform will also educate fans and the public that plastic pollution is a global crisis that not only contaminates our waterways and escalates biodiversity loss, but it is also a major emitter of potent greenhouse gases that drive climate change,” the press release said.

Because 99 percent of plastics are made from fossil fuels, their production, use and disposal contributes to global heating. According to IUCN, every year a minimum of 14 tons of plastics enter the world’s oceans, where marine species ingest or become entangled by the debris, leading to serious injuries and death.

“If the plastic industry was a country, it would already be the world’s fifth-largest greenhouse gas emitter,” Parley for the Oceans said. “This platform provides more information on the impacts of plastic on our environment and equips the global sailing community with opportunities and tools to become part of the solution.”

A goal of the SailGP Impact League is to make sustainability action an essential part of sports.

“Sailors know the seas – and they know the impacts of plastics and climate change are real. Who better to push for the transformation away from fossil fuels than problem-solvers who are already at the helm and collaborating with the elements?” said Cyrill Gutsch, Parley’s founder and CEO, in the press release. “With SailGP vs Plastic, and through our ongoing alliance with the impact league, we’re making ocean education and experiences more accessible to new audiences, inviting sailors everywhere to explore and share the connections between plastics and climate, and empowering more ocean voices in the movement for solutions.”

The post Sailing Community Introduces New Platform to Fight Plastic Pollution and Climate Change appeared first on EcoWatch.

Following days of heavy rains in Brazil, the country’s southernmost state of Rio Grande do Sul is experiencing severe landslides and flooding. At least 85 people have been killed.

Of the 497 cities in the area, more than two-thirds have been affected by the storms, which have destroyed roads and bridges, reported Reuters.

On Monday, President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva requested that a state of public calamity be declared by Congress. The declaration would free up government funds free from a spending cap imposed by new rules last year.

“We don’t have an estimate yet of what will be necessary,” said Simone Tebet, the country’s minister of planning, budget and management, as Reuters reported. “Only when the water recedes will we see the immense extent of the damage in the state.”

Roughly 150,000 people have been displaced by the floods, with more than 130 still missing, according to state officials, as reported BBC News.

More heavy rain forecast for the coming week is expected to add to the dangerous conditions in the region. Many residents were forced to evacuate, including some vulnerable people aided by rescue workers.

“Despite improvements in parts of the state, some areas will remain under severe conditions for a very long time,” said MetSul Meteorologia, a local weather agency, as Reuters reported.

Canoas resident Flavio Rosa, who is 72, said it was the first time he had seen the annual rains in Rio Grande do Sul cause such widespread damage.

“I’ve seen other floods, but nothing like this,” Rosa said, as reported by Reuters.

Governor of Rio Grande do Sul Eduardo Leite said the death toll could rise substantially as more areas are reached by rescue workers.

“When the rain stops, they have been doing short operations to save as many people as possible. Yesterday (Saturday) [we were] able to intensify operations,” Colonel José Carlos Sallet, Rio Grande do Sul Military Firefighters subcommander, told CNN.

Rescue teams were using inflatable rafts to rescue residents and their pets.

According to railway operator Rumo, the extreme weather had caused train disruptions in the state, Reuters reported.

One of the country’s busiest airports, Salgado Filho International in the state’s capital of Porto Alegre, suspended operations until the end of May at least due to flooding from the Guaiba River, BBC News said.

Local officials said the river had reached 17.4 feet, breaking the previous record from 1941 of 15.6 feet.

The severe storms were caused by an unusual mix of high humidity, hotter than average temperatures and strong winds.

“Rio Grande do Sul has always been a meeting point between tropical and polar air masses,” Francisco Eliseu Aquino, a climatologist, told AFP. “But these interactions intensified with climate change” to create “a disastrous cocktail that makes the atmosphere more unstable and encourages storms.”

The post Flooding and Landslides Kill at Least 85 People in Brazil as Climate Change Forms ‘Disastrous Cocktail’ With Severe Storms appeared first on EcoWatch.

Researchers have found promising signs for a possible increase of Antarctic blue whales, based on surveys spanning from 2006 to 2021.

A team of scientists analyzed data they collected from seven acoustic surveys conducted in the Antarctic region over the 15-year timespan. They used “sonobuoys” to detect marine sounds and ultimately gathered about 3,900 hours’ worth of sounds to review.

In the analysis, the researchers specifically sought out calls of Antarctic blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus intermedia), which are the largest animals on the planet but are currently critically endangered, according to the IUCN Red List.

The researchers explained that the whales’ song sounds are considered a 3-unit vocalization (written as A, B and C throughout the study), and together, the full call is referenced as the Z-call.

They found that Unit A calls were the most widely distributed in the recordings from the sonobuoys. Unit A calls and Z-calls were more prominent in late summer and early fall. D-calls, or non-song calls, were detected most in the summer, during the feeding season. The results were published in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science.

“Antarctic blue whales are critically endangered, and this makes them difficult to find in the vast Southern Ocean, but they make very loud, low frequency calls that we can detect from hundreds of kilometers away, using acoustic technology,” said Brian Miller, lead author of the study and marine mammal acoustician at the Australian Antarctic Division of the Australian Marine Mammal Centre, as reported by Phys.org.

According to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), Antarctic blue whales are not just the largest animal on the planet, but also the loudest. Their calls can reach about 188 decibels, making them louder than a jet engine, and they can be heard hundreds of miles away. This makes it easier and more cost-effective for researchers to use audio to study the whales.

While the findings reveal regular calls from the whales and give hope for a potential increase in the population, the study authors emphasized that more research is needed to determine whether that means the whale population is actually rebounding.

“Maybe they’re getting louder, or maybe they’re calling more frequently. Maybe this population is increasing and that’s why we’re hearing them more often,” Miller told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. “It’s going to take a bit more work for us to be able to answer that conclusively.”

In addition to the acoustic data, the researchers are also using other tools like satellite, video and even artificial intelligence (AI) to build a bigger database on the Antarctic blue whales. This could help provide more information about the whales, their calls and their behaviors, especially relating to the krill they eat. This primary food source for the whales is under stress from fishing and climate change, the study authors noted.

“Passive acoustic monitoring is poised to play a crucial role in future research addressing knowledge gaps about Antarctic blue whales,” Miller said.

The post Acoustic Recordings Reveal Possible Comeback for Critically Endangered Antarctic Blue Whales appeared first on EcoWatch.

Birds are the most welcome wildlife in the landscape garden. They are beautiful, musical, interesting…

The post Planting a Garden for the Birds appeared first on Earth911.

Consumer Reports, Breakthrough Energy, and ICF recently estimated the added cost of living that an…

The post We Earthlings: Choose Your Legacy appeared first on Earth911.

When Chelsea Wood was a child, she would often collect Periwinkle snails on the shores of Long Island.

“I used to pluck them off the rocks and put them in buckets and keep them as pets and then re-release them,” Wood said. “And I knew that species really well.”

It wasn’t until years later that Wood learned that those snails were teeming with parasites.

“In some populations, 100 percent of them are infected, and 50 percent of their biomass is parasite,” Wood said. “So the snails that I had in my bucket as a child were not really snails. They were basically trematode [parasites] that had commandeered snail bodies for their own ends. And that blew my mind.”

Wood, now a parasite ecologist at the University of Washington, sometimes refers to parasites as “puppet masters,” and in many cases, it’s not an exaggeration. Some can mind-control their hosts, for example, causing mice to seek out the smell of cat pee. Others can shape-shift their hosts, physically changing them to look like food. And their ripple effects can reshape entire landscapes.

For centuries, people have thought of parasites as nature’s villains. They often infect people and livestock. In fact, parasites are by definition bad for their hosts, but today, more scientists are starting to think about parasites as forces for good.

“I don’t think anyone is born a parasitologist. No one grows up wanting to study worms,” Wood said. “Somewhere along the way, I like to say, they got under my skin. I just fell in love with them. I couldn’t believe that I’d gotten that far in my biology education and no one had ever mentioned to me that parasites are incredibly biodiverse, ubiquitous, everywhere.”

On a cloudy August morning, Wood took me to Titlow Beach in Washington state, one of her team’s research sites. Back in the 1960s, one of Wood’s research mentors had sampled shore crabs here. At the time, the area was very industrial and heavily polluted. But when researchers, including Wood, came back to collect samples half a century later, the beach had transformed. The water was cleaner and the shorebirds had returned, but those weren’t the only promising signs: The crabs were now full of trematode worms, a type of parasite that jumps between crabs and birds.

Chelsea Wood kneels to search for shore crabs at a beach in Tacoma, Washington. She will later dissect the crabs to search for parasites. Jesse Nichols / Grist

The parasites were a sign that the local shorebirds were doing great, Wood explained.

As scientists have learned more about parasites, some have argued that many ecosystems might actually need them in order to thrive. “Parasites are a bellwether,” she said. “So if the parasites are there, you know that the rest of the hosts are there as well. And in that way they signal about the health of the ecosystem.”

To understand this counterintuitive idea, it’s helpful to look at another class of animals that people used to hate: predators.

For years, many communities used to treat predators as a kind of vermin. Hunters were encouraged to kill wolves, bears, coyotes, and cougars in order to protect themselves and their property. But eventually, people started noticing some major consequences. And nowhere was this phenomenon more apparent than in Yellowstone National Park.

In the 1920s, gray wolves were systematically eradicated from Yellowstone. But once the wolf population had been eliminated from the park, the number of elk began to grow unchecked. Eventually, herds were overgrazing near streams and rivers, driving away animals including native beavers. Without beavers to build dams, ponds disappeared and the water table dropped. Before long, the entire landscape had changed.

In the 1990s, Yellowstone changed its policy and reintroduced gray wolves into the park. “When those wolves came back in, it was like a wave of green rolled over Yellowstone,” Wood said. This story became one of the defining parables in ecology: Predators weren’t just killers. They were actually holding entire ecosystems together.

“I think there’s a lot of parallels between predator ecology and parasite ecology,” Wood said.

Like the gray wolves in Yellowstone, scientists are just starting to recognize the profound ways that ecosystems are shaped by parasites.

Take, for example, the relationship between nematomorphs, a type of parasitic worm, and creek water quality. The worms are born in the water, but spend their lives on land inside of bugs, like crickets or spiders.

At the end of their lives, nematomorphs need to move back to the water to mate. Instead of making the dangerous journey themselves, they trick their infected hosts into giving them a ride by inducing a “water drive,” an impulse on the part of its insect host to immerse itself in water. The insect will move to the edge of the water, consider it for a little while and then jump in — to its own death, but to this parasite’s benefit.

The story doesn’t end there. In a way, the entire creek ecosystem relies on a worm trying to hitch a ride to the water. Fish eat the bugs that throw themselves in the water. In fact, one species of endangered trout gets 60 percent of its diet exclusively from these infected bugs. “So essentially, the parasite is feeding this endangered trout population,” Wood said.

With less of the threat associated with hungry fish, the native insects in the stream can thrive, eating more algae and thereby giving the creek clear water.

Parasites make up an estimated 40 percent of the animal kingdom. Yet, scientists know next to nothing about millions of parasite species around the world. The main parasites that scientists have spent a lot of time studying are the ones that infect farm animals, pets, and people.

Many of these alarming parasites, like ticks or the parasitic fungus that causes Valley Fever, are expected to increase due to climate change. But no one actually knows what climate change means for parasites, broadly — or how any big change in parasites might reshape the world. “There’s this general sense that infection is on the rise, that parasites and other infectious organisms are more common than they used to be,” Wood said. “At least for wildlife parasites, there really isn’t long-term data to tell us whether that impression that we have is real,” Wood said. “We had to invent a way to get those data,” Wood said.

Wood had an unconventional idea of where to look: a collection of preserved fishes locked away in a museum basement.

The University of Washington Fish Collections is home to more than 12 million samples of preserved fishes, dating all the way back to the 1800s. But the thousands of jars lining the collection shelves also contain something else: all the parasites living inside the fish samples.

“So much has been discovered from museum specimens that we tucked away at one time, and then pulled off the shelf 100 years later,” said Wood. “It’s really remarkable to get to peer back in time the way that you do when you open up a fish from a hundred years ago. It’s the only way that we’ll know anything about what the oceans were like, parasitologically, that long ago.”

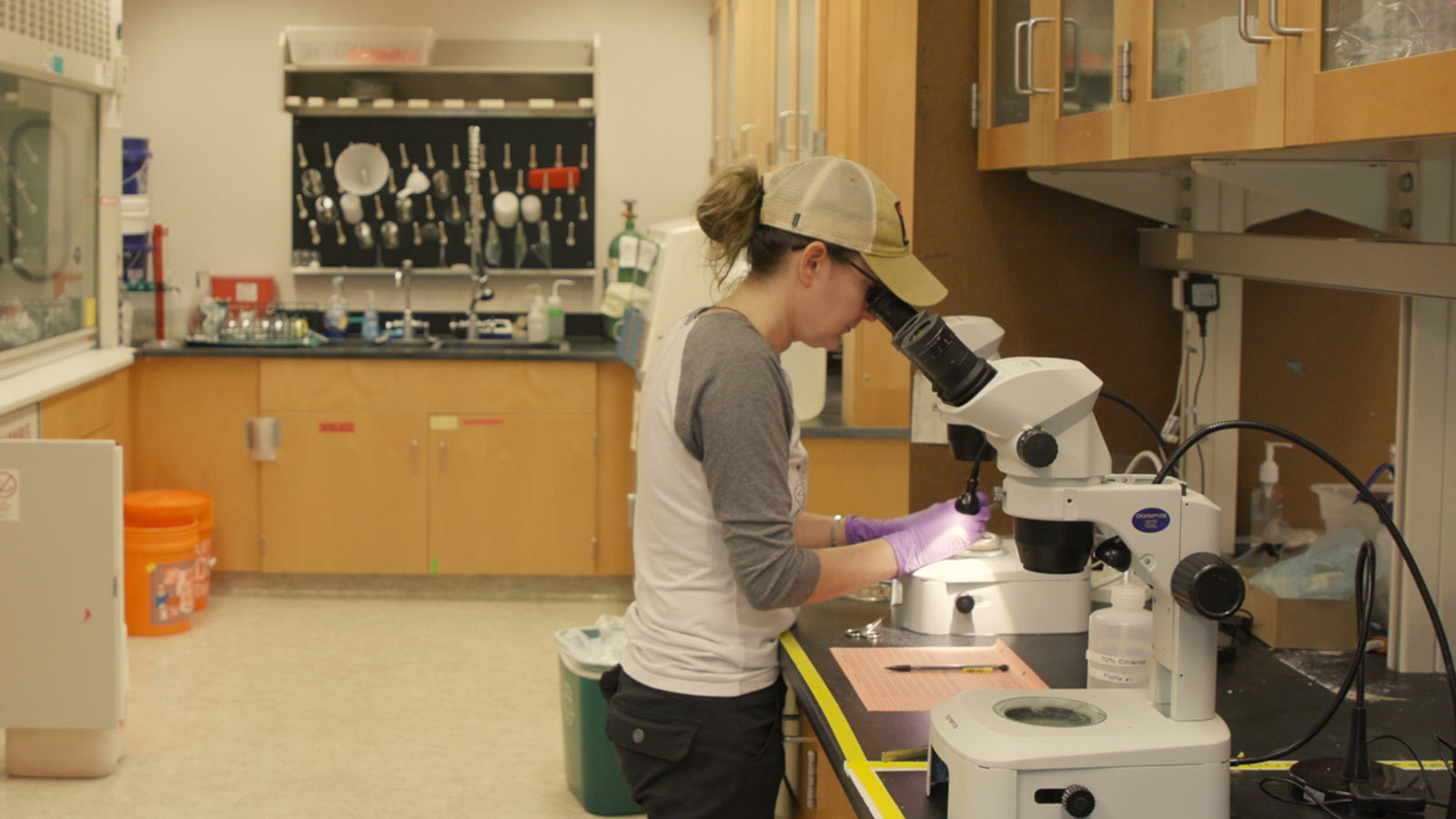

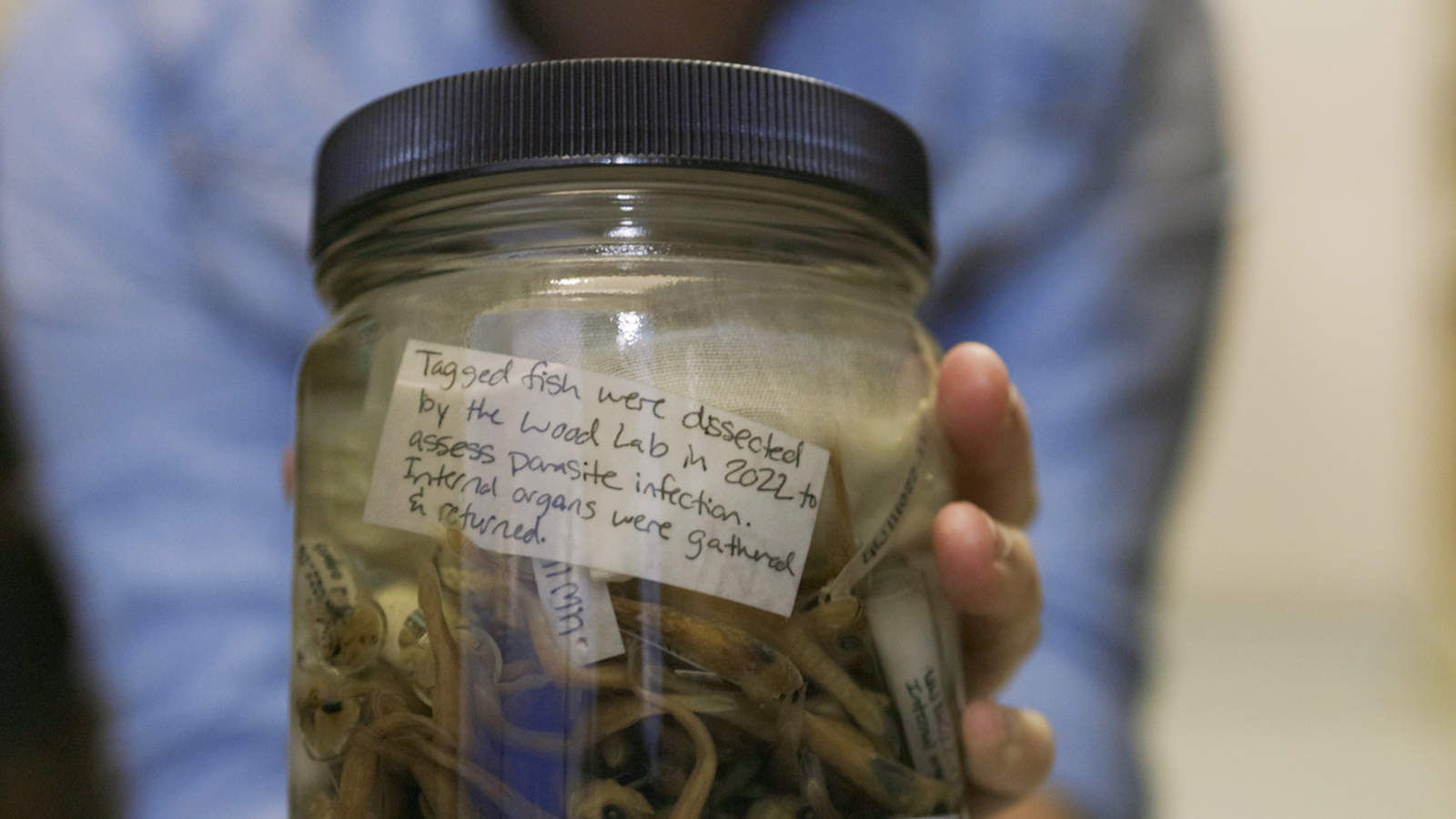

Chelsea Wood dissects fish samples in her lab at the University of Washington. Jesse Nichols / Grist

Wood and her team spent over two years opening up jars and surgically dissecting the parasites from within. Under microscopes, they identified and counted the parasites before returning everything for future study. In the end, they found more than 17,000 parasites.

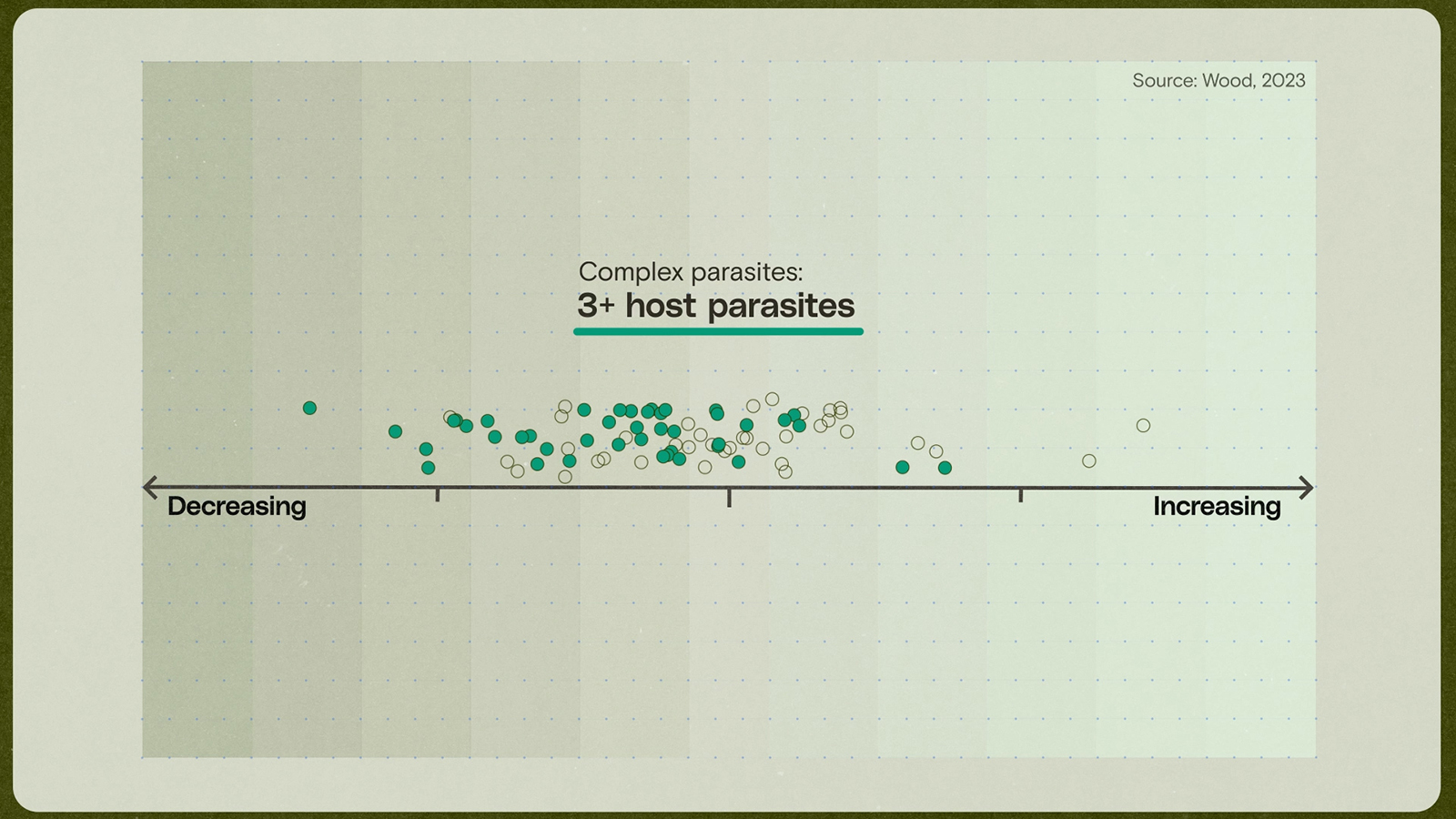

Looking at the number of parasites found in fishes over time, the researchers found a mix of winners and losers, but there was one big class of parasites that was unequivocally declining: complex parasites, the kinds that need several different host species in order to survive. That type of parasite declined an average of 10 percent each decade, the team found.

In Wood’s investigation, there was only one factor that perfectly explained the decline in parasites: It wasn’t chemicals or overfishing. It was climate change. It made a lot of sense: Complex parasites can only survive if everyone one of those host species are around. If just one type of host goes missing? “Game over. That’s it for that parasite,” Wood said. “That’s why we think that these complex life cycle parasites are so vulnerable: because things are shifting, and the more points of failure you have, the likelier you are to fail.”

Wood said that, before this study, researchers had no idea climate change was wiping out this important class of parasites.

“It’s likely a collateral impact,” she said. “We don’t even have a handle on how many parasites there are in the world, much less the scale of parasite biodiversity loss right now. But the early indications are that parasites are at least as vulnerable as their hosts, and potentially more vulnerable.”

Wood says that it’s important for people to understand that parasites play huge and complex roles in nature, and if we ignore what we can’t see, we risk missing out on understanding how the world really works. “We all have a reflexive distaste for parasites, right? We take drugs, we apply chemicals, we spray, Wood said. “Our argument is that parasites are just species. They’re part of biodiversity, and they’re doing really important things in ecosystems that we depend upon them for.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Nature can’t run without parasites. What happens when they start to disappear? on May 7, 2024.