The rising cost of homeowner’s insurance is now one of the most prominent symptoms of climate change in the United States. Major carriers like State Farm and Allstate have pulled back from offering fire insurance in California, dropping thousands of homeowners from their books, and dozens of small insurance companies have collapsed or fled from Florida and Louisiana following recent large hurricanes.

The problem is fast becoming a crisis that stretches far beyond the nation’s coastal states. That’s owing to another, less-talked-about kind of disaster that has wreaked havoc on states in the Midwest and the Great Plains, causing billions of dollars in damage. In response, insurers have raised premiums higher than ever and dropped customers even in inland states such as Iowa.

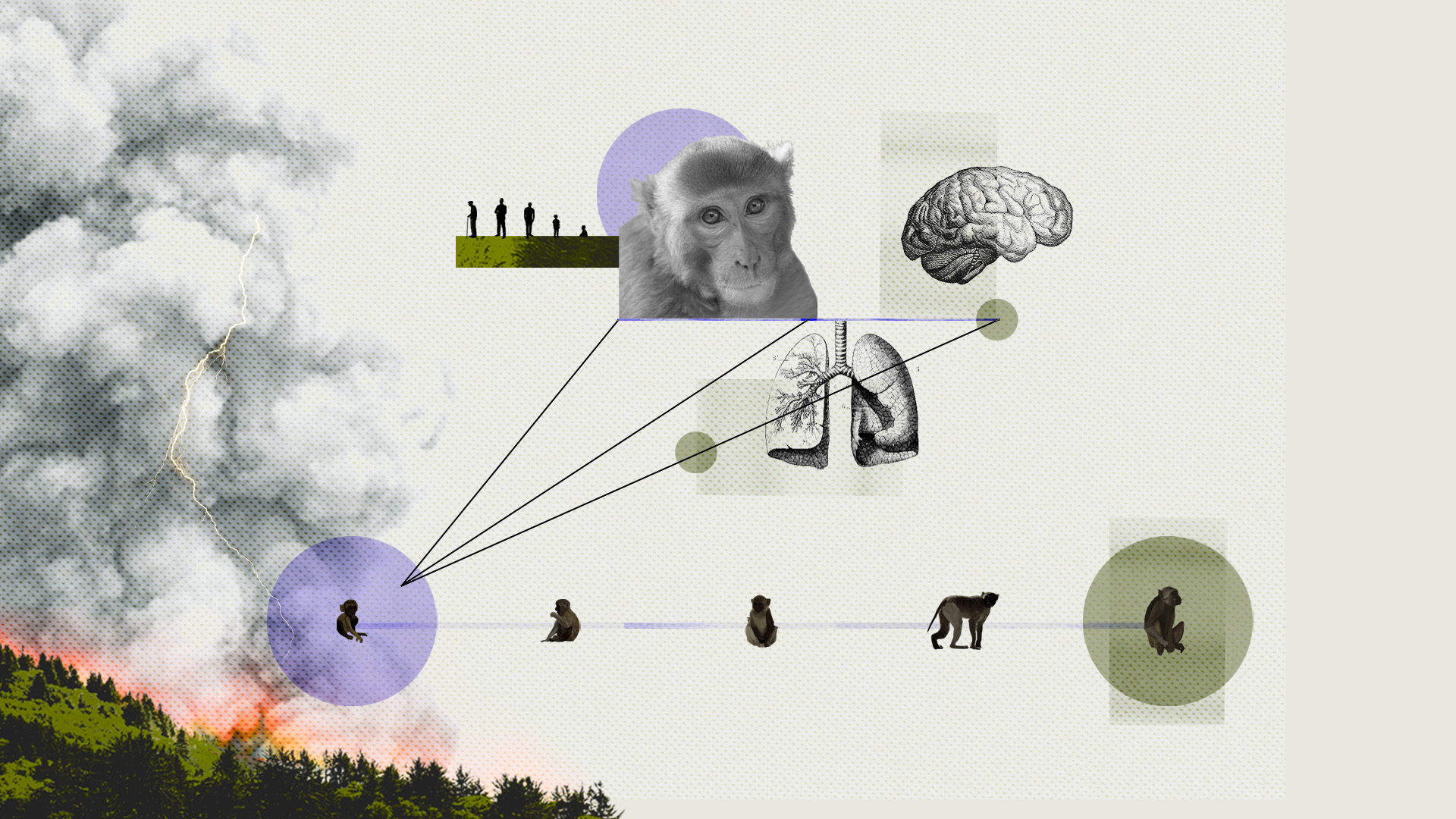

These so-called “severe-convective storms” are large and powerful thunderstorms that form and disappear within a few hours or days, often spinning off hail storms and tornadoes as they shoot across the flat expanses of the central United States. The insurance industry refers to these storms as “secondary perils”—the other term of art is “kitty cats,” a reference to their being smaller than big natural catastrophes or “nat cats.”

But the damage from these secondary perils has begun to add up. Losses from severe convective storms increased by about 9 percent every year between 1989 and 2022, according to the insurance firm Aon. Last year these storms caused more than $50 billion in insured losses combined—about as much as 2022’s massive Hurricane Ian. No single storm event caused more than a few billion dollars of damage, but together they were more expensive than most big disasters. The scale of loss sent the insurance industry reeling.

“As insurers, our job is to predict risk,” said Matt Junge, who oversees property coverage in the United States for the global insurance giant Swiss Re. “What we’ve missed is that it wasn’t a big event that had a big impact, it was a bunch of small surprise events that just added up. There’s this kind of this reset where we’re saying, ‘Okay, we really have to get a handle on this.’”

Part of the reason for this steady accumulation is that more people are moving to areas that are vulnerable to convective storms, which raises the damage profile of each new tornado or hailstorm. The cost of rebuilding a home has increased due to inflation and supply-chain shortages, which drives up prices. But climate change may also be playing a role: Convective storms tend to form in hot, moist, and unstable weather conditions.

“We have such a dearth of observations about hailstorms and tornadoes, so the trend analysis is tricky,” said Kelly Mahoney, a research scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, who studies severe convective storms. “But you are taking storms that are fueled by heat and moisture, and you are watching them develop in a world that is hotter and moister than ever. It’s a tired analogy these days, but it’s still true here, of loaded dice or a stacked deck.”

Climate attribution is much harder for these ephemeral storms than it is for hurricanes and heat waves, Mahoney said, but it stands to reason that climate change will have some influence on how and where they develop. Warming has already caused the geographic range of “Tornado Alley” to extend farther south and east than it once did, delivering more twisters to states like Alabama and Mississippi.

Whatever the cause, this loss trend is making business much harder for many insurance companies. Most vulnerable are the small regional insurers with large clusters of customers in one state or metropolitan area. When a significant storm strikes, these companies have to pay claims to huge portions of their risk pool, which can drain their reserves and push them toward insolvency.

“The local mutuals, you have a couple storms, you have a bad year, and they’re in trouble, because all their business is here and that risk isn’t spread out,” said Glen Mulready, the insurance commissioner of Oklahoma. The state has some of the highest insurance premiums in the country, and Mulready said many insurers are now refusing to write new policies for homes with old roofs that are vulnerable to collapse during tornadoes and hailstorms.

Even large “reinsurers,” which sell insurance to insurance companies around the world, are feeling the sting from these storms. Global reinsurance firms such as Swiss Re take in premium revenue from all over the globe, insuring earthquakes in Japan as well as hurricanes in Florida, so they aren’t vulnerable to collapse during local disasters, even major ones. But the increasing trend of “attritional” losses from repeated convective storms does threaten to cut into their profit margins.

“We have less of a concern about the tail on these types of events,” said Junge of Swiss Re, using the industry term for the costliest disasters. “The concern for us is just the impact on earnings.”

Ed Bolt, the mayor of Shawnee, Oklahoma, has seen this impact up close. A tornado raged down his town’s main boulevard last year and destroyed more than 2,000 buildings, knocking the roof off Bolt’s own house. His insurance company paid to replace the roof, but it mailed him a letter a few months ago with a notice that his annual premium was going to increase by 50 percent, reaching around $3,600 a year.

“The cost used to tick up and tick up a little bit, but last year we knew we would get a big hit because of the tornado,” Bolt told Grist. “I’m sure that would be a pretty consistent experience across town.”

Most states require insurers to get permission from regulators before they raise rates, which presents governments with a tough dilemma. If they raise rates, they make it harder for homeowners to keep up with their insurance payments, and they also risk dampening property values. If they keep rates down, insurers might react by ceasing to write new policies or pulling out of the state. Mulready, the Oklahoma commissioner, says he had one national insurer leave his market earlier this year.

Still, the Midwest has yet to encounter a large-scale exodus, and industry representatives say it’s unlikely that they will pull out of the region the way they have from California. But it’s a safe bet that insurers will keep raising premiums as high as states will let them. Insurers may also raise deductibles, setting a higher minimum amount of damage before insurance kicks in. The upshot is a bigger financial burden for homeowners in fast-growing metro areas like Denver, where insurers’ storm exposure has skyrocketed in recent years.

Perhaps the worst part of the problem is that most states have made little progress in preparing for these storm events. Florida imposed a strict building code after Hurricane Andrew in 1992, and most newer homes in the state can withstand high winds. The housing stock in the central United States is far less resilient to tornado winds and hail, and just a few cities have forced builders to fortify homes against those hazards.

Erin Collins, the lead state policy advocate at the National Association of Mutual Insurance Companies, the nation’s largest insurer trade group, said carriers might have to keep raising rates until the nation’s housing stock becomes more resilient to severe storms.

“It’s going to take community-scale hardening to bend that loss curve down,” she told Grist.

That won’t be easy. Insurers need to convince large home builders that they should build with more expensive, storm-resistant materials, and they also need to nudge millions of people in existing homes to upgrade their roofs and windows, which can cost tens of thousands of dollars. Because severe convective storms can strike such a wide geography, it will take a long time for this mitigation work to “bend the loss curve down.”

The good news is that we know how to build storm-resistant homes, and there’s proof that building better makes a big difference, says Ian Giacomelli, a senior meteorologist at the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety, a nonprofit that advocates for stronger building standards.

Giacomelli points to the city of Moore, Oklahoma, which rolled out some of the strictest storm-resilience standards in the country after it suffered three devastating tornadoes in two decades. Now almost the city’s entire housing stock has roofs that can bounce off large hail storms and strong joints that prevent roofs from flying off during tornado events. Giacomelli says the nation’s current insurance crisis would likely ease up if more cities followed Moore’s lead.

“I think the solutions are coming into focus,” he told Grist. “It’s more about can we get the will to do them.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How ‘kitty cats’ are wrecking the home insurance industry on May 16, 2024.