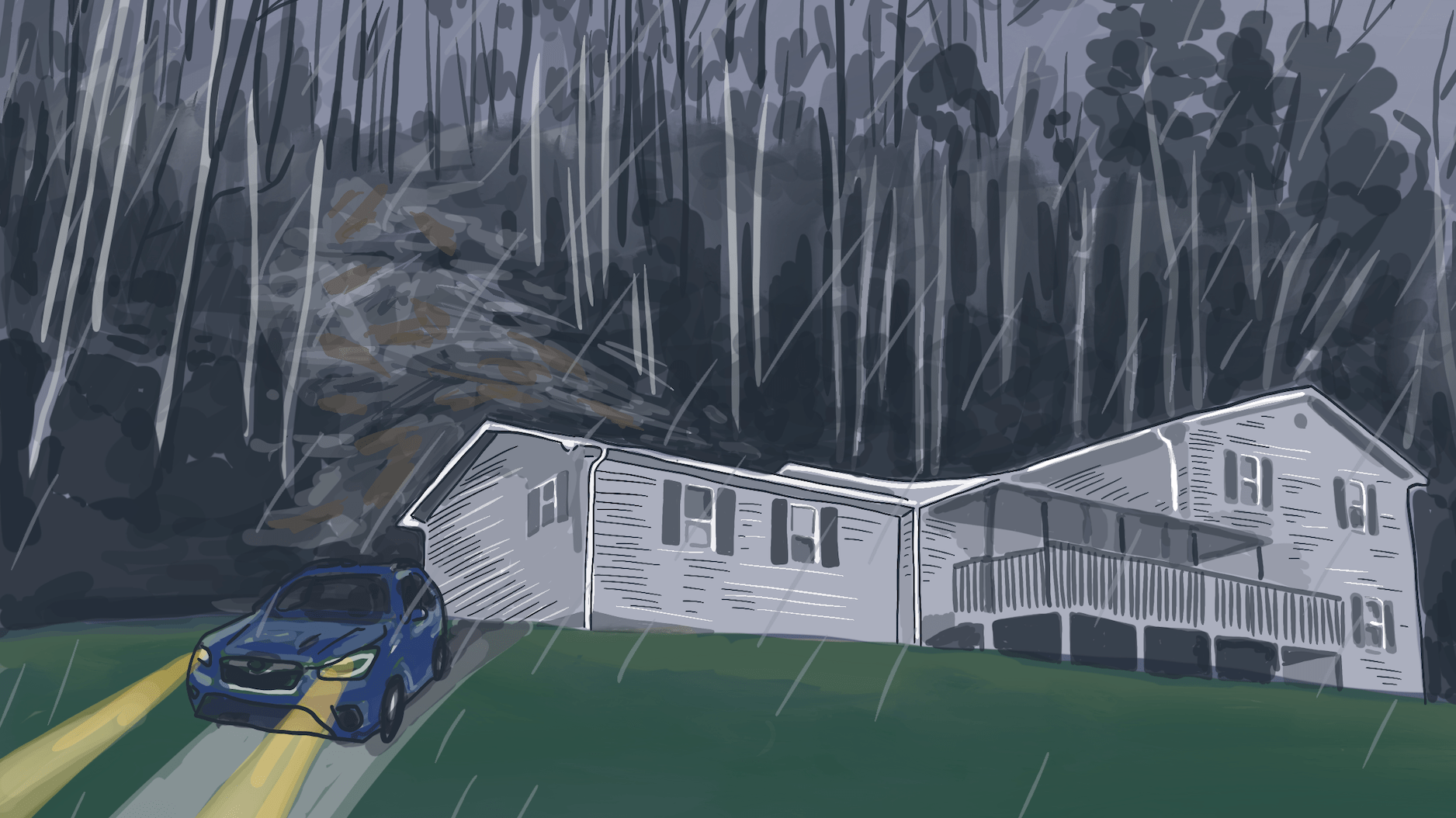

The dream that haunts Christine White is always the same, and though it comes less frequently, it isn’t any less terrifying.

The black water comes rushing at the witching hour, barrelling toward her front door in Lost Creek, Kentucky. She’s outside, getting her grandson’s toys out of the yard. It hits her in the neck and knocks her off her feet before racing down a street that has become a vengeful river. She and her husband run to a hillside and scramble upward, grabbing hold of tree roots and branches. She finds her neighbors huddled at the top of the hill. As dawn comes, everything is unrecognizable, the land shifted, houses torn from foundations. They begin to walk through the trees, over the strip mine, out of the forest, in their pajamas and underwear with whatever they were able to carry when they fled.

Then she wakes up.

That night used to replay every time White went to sleep. She started taking antidepressants six months ago, something she felt ashamed of at first but doesn’t anymore. They’ve helped a little, but the dream still haunts her, lightning-seared and vivid.

It’s been one year since catastrophic floods devastated eastern Kentucky, taking White’s home and 9,000 or so others with it. Her current abode — a camper on a cousin’s land — has become, if not home, no longer strange. But it’s the closest thing to home she’ll get till her new house, in another county, is finished. Lost Creek, though, is all but gone forever. What houses remain are empty husks. Some are nothing more than foundations overgrown with grass.

White is never going back. “All the land is gone,” she said.

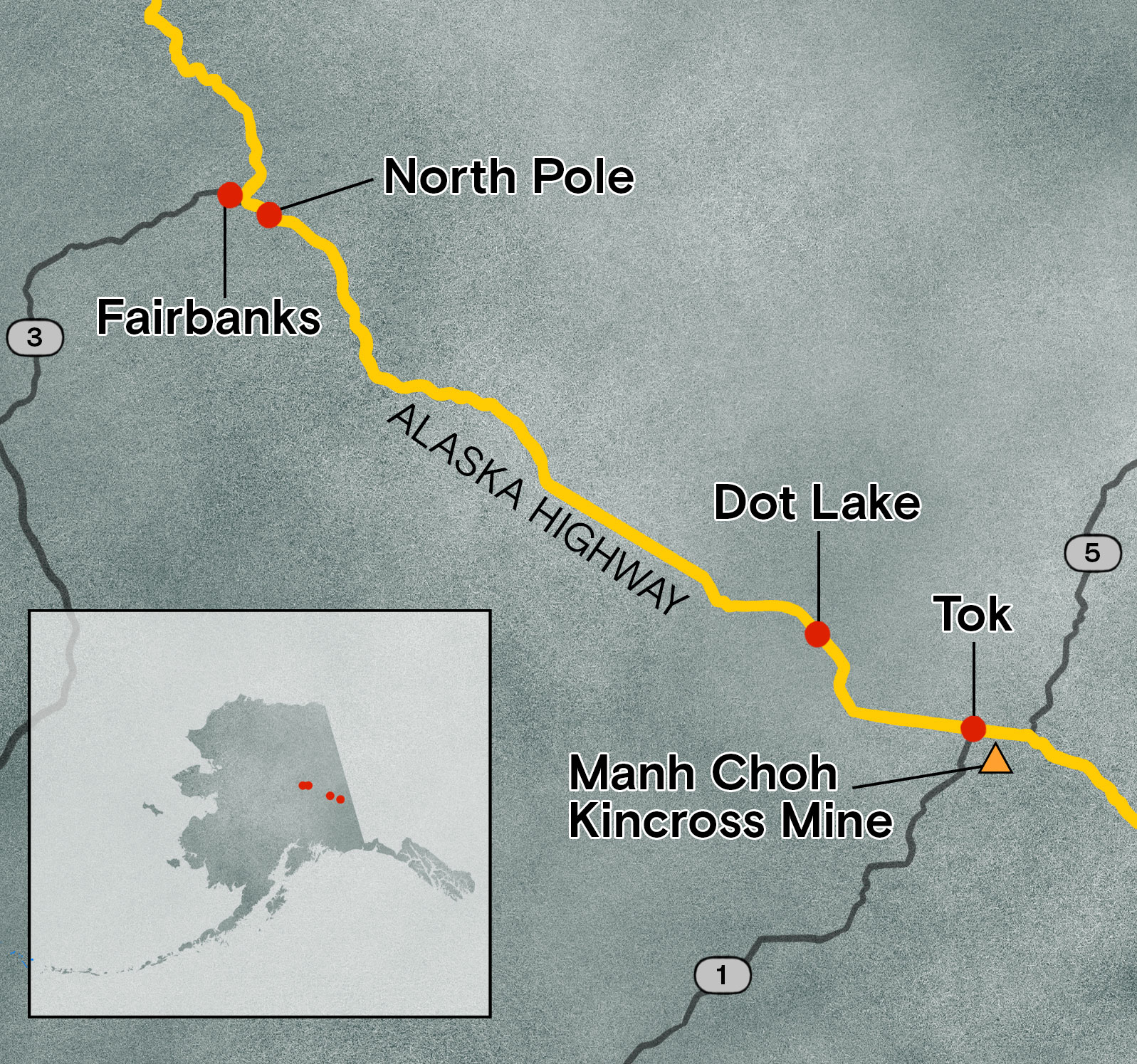

In the early hours of July 28, 2022, creeks and rivers across 13 counties in eastern Kentucky overran their banks, filled by a month’s worth of rain that fell in a matter of days The water crested 14 feet above flood stage in some places, shattering records. All told, 44 people died and some 22,000 people saw their homes damaged —staggering figures in a region where some counties have fewer than 20,000 residents. Officially, the inundation destroyed nearly 600 homes and severely damaged 6,000 more. A lot of folks say that tally is low, based on the number of residents who sought help from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. As of March about 8,000 applications for housing assistance had been approved. That’s half the number the agency received.

The need for help, specifically housing assistance, was, and remains, acute. Most people here live on less than $30,000 a year, and at the time of the disaster, no more than 5 percent had flood insurance. Multitudes of nonprofits, church and community organizations, businesses, and government agencies have spent months pitching in as best they can. Yet there is a feeling among the survivors that no one’s at the rudder, and it’s everyone for themselves.

President Biden issued a federal disaster declaration the day after the flood, and his administration has disbursed nearly $300 million in aid so far. The state pitched in, too, housing 360 families in trailers parked alongside those from FEMA. Many of those have moved on to more permanent housing, but up to 1,800 are still awaiting a solution.

Some in the floodplains are taking buyouts — selling their homes to the federal government, which will essentially make the land a permanent greenspace. It’s a form of managed retreat, a ceding of the terrain to a changing climate. Some local officials openly worry that the approach doesn’t solve the biggest problem everyone faces: figuring out where on Earth people are going to live now. Eastern Kentucky was grappling with a critical shortage of housing even before the flood, and much of the land available for construction lies in flood-prone river bottoms. That has people looking toward the mountaintops leveled by strip mining.

Grist / Katie Myers

Kate Clemons, who runs a nonprofit meal service called Roscoe’s Daughter, sees this crisis every day. As the water receded, she started serving hot meals in the town of Hindman a few nights each week, on her own dime. She figured it would be a months’ work. She’s still feeding as many as 700 hungry people every week. Recently, an apartment building in Hazard burned down, displacing nearly 40 people. Some of them were flood survivors. They’ve joined the others she’s taken to helping find homes.

“There’s no housing available for them,” she said.

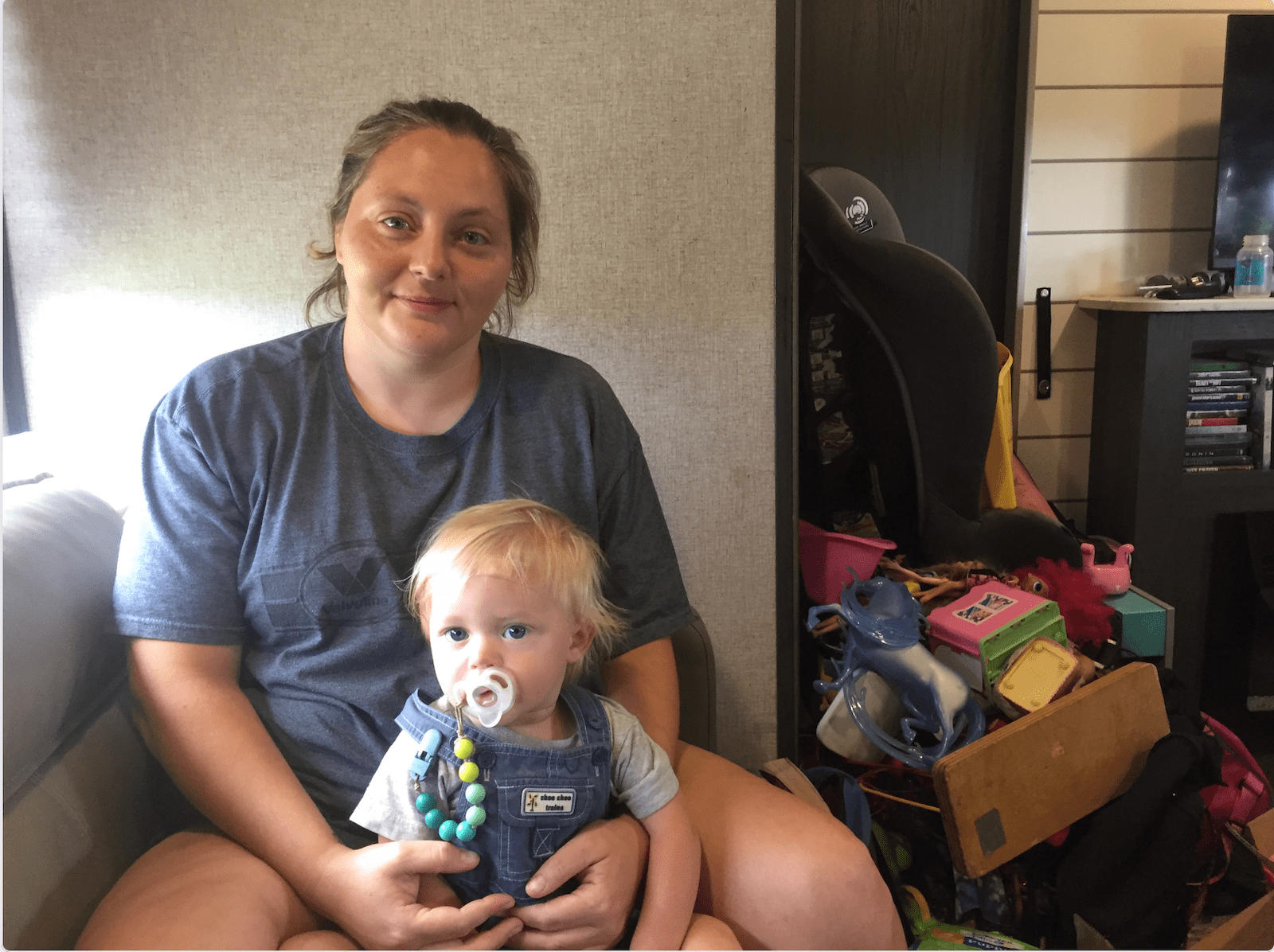

Clemons often brings food to Sasha Gibson, who after the flood moved with her boyfriend and nine children into two campers at Mine Made Adventure Park in Knott County. At first, she felt optimistic. “I was hoping that this would open up a new door to something better,” she said, after asking her children to go to the other trailer so she could sit for the interview in her cramped quarters. “Like this is supposed to be a new chapter in our lives.”

But the park, built on what was once a strip mine, became purgatory instead.

Gibson, who lived on family land before the rains came, wants to leave. It’s just that the way out isn’t apparent yet. Many rentals won’t take so big a family. It doesn’t help that many of their identity documents were lost to the flood, making the search that much harder. She got some help from FEMA, but said the money went too quickly.

A caseworker helps navigate a labyrinth of agencies designed to help Kentucky flood victims, and they’ve put in applications at a grab bag of charities building housing. One has told Gibson her case looks promising, but she’s still waiting to hear a final word. Other applications are so long and such a crapshoot — one ran 40 pages, for a loan she’d struggle to pay back — that she’s too tired to put them together.

“It’s a big what-if game,” she said. “They’re not reaching out to you. You’re expected to call them.”

Meanwhile, ATV riders sometimes ride through to the park, kicking up dust and leaving a mess in the restrooms. Gibson tries not to resent them. It’s not their fault she’s stuck.

“While it’s great and, like, they’re having a good time, it’s not a great time for us because we feel like we’re stuck here and we’re, like, an inconvenience and we’re in the way,” she said. “We don’t want to bother anybody.”

As extreme weather intensifies due to climate change, stories like Gibson’s will play out in more and more communities. Though eastern Kentucky hadn’t flooded like this since 1957, parts of the state could face 100-year floods every 25 years or so. About half of all homes in the region hit hardest by last year’s floods — Knott, Letcher, Perry, and Breathitt counties — are at risk for extreme flooding.

Some residents worry that the legacies of surface mining – lost topsoil and tree cover, a ruined water table, and waste retention dams like the one that may have failed near Lost Creek, drowning it – will make communities more vulnerable to floods, compounding the effects of generational poverty and aging rural infrastructure. Housing needs to be built, and some say it needs to go up on the only high, flat land available — that is, the very same strip mines that contributed mightily to this whole problem in the first place.

High ground, especially former strip mines, in the region tends to be off limits. A study completed in the 1970s showed that most of what is available belongs to land companies, coal companies, and other private interests. About 1.5 million acres is believed to have been mined. Many of those sites are too remote to be of much use for housing, though, and those that are closer to town typically have seen commercial development. As the flood recovery has dragged on, though, some of these entities have decided to donate some of what they hold so that there might be more residential construction. Other parcels have been donated by landowning families with cozy relationships to the coal industry, though that hasn’t always gone smoothly.

Chris Doll is vice president of the Housing Development Alliance, a nonprofit dedicated to building single-family homes for low-income families. It was beating the drum of eastern Kentucky’s crisis long before the flood. The situation is even more dire now. Without an influx of new construction, he argues, the local economy will spiral even further.

On an overcast and gentle day in June, Doll walked around a former strip mine turned planned development in Knott County called Chestnut Ridge. It sits near a four-lane highway and close to other communities, with ready access to water lines. The Alliance is working with other nonprofits to build around 50 houses here, along with, it hopes, 50 to 150 more on each of two similar sites in neighboring counties. A $13 million state flood relief fund has committed $1 million to the projects.

Grist / Katie Myers

The road leading to what could, in just a few years, be a bustling neighborhood opened up into a bafflingly flat landscape, almost like a wooded savanna. It was wide open to the sunshine, unlike the deep hollers and coves that characterize this part of eastern Kentucky. To an untrained eye, it appeared to be a healthy ecosystem. Look closer, though, and one sees the mix of vegetation coal companies use to restore the land: invasive autumn olive, scrubby pine trees, and tall grasses, planted mostly for erosion control.

Still, it’s ideal land for housing, and most folks around here won’t mind the landscaping. Doll said the number of people who need help is overwhelming, and his team can’t help everybody. But they hope to build as many houses as they can.

“There are so many people that have so many needs that I am of the mindset that I will help the person in front of me,” Doll said. “And now we can turn them into homeowners. If that’s what they want.”

On a hillside overlooking another mine site, Doll and I walked up to the ridge to see if we could get a better view of the terrain. It is covered in a thicket of brush, too dense to see beyond. The path wound toward a small clearing, where worn headstones and stone angels sit undisturbed. Family cemeteries are protected from strip mining, and this one was clearly still cared for; the bouquets at the angels’ feet were fresh. The lifecycle of coal had come and made its mark and gone.

“You can see where they cut out,” Doll said. “They just entirely destroyed that mountain. It’s such a wild thing to think that strip mine land is going to be part of the solution.”

Doll thinks of it as a post-apocalyptic landscape, or maybe mid-apocalyptic, ripe for renewal, but still carrying the weight of its past. The land was gifted by people whose money was made from coal, after all.

“And, you know, it’s great that they’re giving land back,” he said. “I would prefer if it was still mountains, but if it was mountains, we couldn’t build houses on it. So yeah, it’s ridiculously complex.” He shrugged. “Bigger heads than mine.”

He squelched across the mud and back to the car. In the summer heat, two turkeys retreated into the shade of a scrubby pine grove, their tracks etched in the mud alongside hoofprints, probably from deer and elk. The place was alive, if not exactly the way it was before.

The former strip mine developments are financed in part by the Team Kentucky flood relief fund created by the governor’s office. Beyond the four projects already in motion, eastern Kentucky housing nonprofits like the Housing Development Alliance are working with landowners, local officials and the governor to secure more land in hopes of building hundreds more homes.

“Working together – and living for one another – we’ve weathered this devastating storm,” Governor Andy Beshear said last week during a press conference outlining progress made since the flood. “Now, a year later, we see the promise of a brighter future, one with safer homes and communities as well as new investments and opportunities.”

That said, nothing is fully promised just yet, and the process could take years. The homes will be owner-occupied and residents will carry a mortgage, but housing advocates hope to lower as many barriers to ownership as possible and help families with grants and loans. Applications for the developments are expected to open within a couple of months. The plans, thus far, call for an “Appalachian look and feel” that combines an old-style coal camp town and a suburban subdivision to create single-family homes clustered in wooded hollers. Though some might argue that density should be the priority, local housing nonprofits want developments that feel like home to people used to having a bit of land for themselves.

The Housing Development Alliance has built houses on mined land before, and some of them are among those given to 12 flood survivors thus far. Alongside other entities, it has also spent the year mucking, gutting, and repairing salvageable homes, often upgrading them with flood-safe building protocols. Even that comparatively small number was made possible through support from a hodgepodge of local and regional nonprofits, and the labor of the Alliance’s carpenters has been supplanted with volunteer help.

Though the Knott County Sportsplex, a recreation center built on the mineland next to Chestnut Ridge, appears to be sinking and cracking a bit, Doll said houses are too light to cause that kind of trouble. Nonetheless, geotechnical engineers from the University of Kentucky, he said, are studying the land to make sure there won’t be any unpleasant surprises. The plan is for the neighborhoods to be mapped out onto the landscape with roads and sewer lines and streetlights, all of which require the involvement of myriad county departments and private companies; then the Alliance and its partners will come in and do what they do best, ideally as further disaster funding comes down the line.

Still, all involved say that there’s no way they can build enough houses to fill the need.

Grist / Katie Myers

More federal funding will arrive soon through the U.S. Housing and Urban Development disaster relief block grant program. It allocated $300 million to the region, and organizations like the Kentucky River Area Development District are gathering the information needed to prove to the feds the scale of the region’s need. Some housing advocates are critical of this process, though.

Noah Patton, a senior policy analyst with the Low-Income Housing Coalition, said HUD grants are too unpredictable to forge long-term plans. “One reason it’s exceptionally complicated is because it is not permanently authorized,” he said. A president can declare a disaster and direct the agency to release funds, but Congress must approve the disbursement. Although it all went smoothly in Kentucky’s case, the unpredictability means there are no standing rules on how to allocate and spend funding.

“Oftentimes, you’re kind of starting from scratch every time there’s a disaster,” Patton said.

Local development districts, such as the Kentucky River Area Development District, are holding meetings around the affected counties, urging people to fill out surveys so it can collect the data needed to apply for funding from the federal program. And HUD is overhauling its efforts to address criticism of unequal distribution of funds. Still, the people who might benefit from these block grants may not see the homes they’ll underwrite go up for a few more years, Patton said.

On the state level, housing advocates have been pushing the legislature for more money to flow toward permanent housing. Many also say the combined state, FEMA and HUD assistance isn’t nearly enough. One analysis by Eric Dixon of the Ohio River Valley Institute, a nonprofit think tank, pegged the cost of a complete recovery at around $453 million for a “rebuild where we were” approach and more than $957 million to incorporate climate-resilient building techniques and, where necessary, move people to higher ground.

Sasha Gibson has heard rumors of the new developments. She’s somewhat interested insofar as they can get her out of limbo. Until she sees these houses going up, though, they’ll be just another vague promise in a year of vague promises that have gotten her nowhere but a dusty ATV park. It’s been, to put it bluntly, a terrible year, and the moments where the family’s had hope have only made the letdowns feel worse.

“I have no hope to rely on other people,” she said. “I don’t want to give somebody else that much power over me. Because then you’ll just wind up disappointed and sad. And it’s even sadder when you have all of these little eyes looking at you.”

As Gibson waits, others long ago decided to remain where they were and rebuild either because they could or because there wasn’t another choice.

Tony Potter, who’s lived on family land in the city of Fleming-Neon since birth, has spent the past year in what amounts to a tool shed. It’s cramped and doesn’t even have a sink, but the land under it belongs to him, not a landlord or bank. It’s a piece of the world that he owns, and because a monthly disability check is his only income, he doesn’t have much else and probably couldn’t afford a mortgage or rent. Asked if he’d consider moving, he scoffed.

“You put yourself in my shoes,” he said.

He can’t believe FEMA would offer to buy someone’s land, or that anyone would take the government up on the offer. “I mean, my God, why in the hell you wanna buy the property and then tell them they can’t live on it?” he said. “What kind of fool would sell their property? Why would you want to sell something and then go rent something?”

James Hall, who also lives in Neon, lost everything but is staying put, in part because he doesn’t think it’ll happen again. The words “thousand-year flood” must mean something, he said. But that didn’t keep him from putting his new trailer a foot and a half higher just in case. He might bump that up to 3 feet when he has a minute. Through it all, he’s kept his dry sense of humor. “If the flood comes again,” he said, “I’m gonna get me a houseboat.”

That kind of outlook buoys Ricky Burke, the town’s mayor. He said the community’s used to flooding – the city sits in a floodplain at the intersection of the Wrights Fork and Yonta Fork creeks – but last year’s was by far the worst. Water and mud plowed through town with enough force to shatter windows. People went without water and electricity for months in some places. A few buildings, like the burger drive-in on the corner at the edge of town, have been repaired, but others remain gaunt and empty.

Still, Burke, a diesel mechanic who was elected in November, is confident the town will pick itself up. He’s heard talk that Neon might need to move some of its buildings, that a return to form simply isn’t viable. He’s dismissive of such a notion. What Neon needs, he believes, is a big party, and he’s planning to celebrate the community’s resilience with flowers, music, and a gathering on the anniversary of the flood.

“These people in Neon ain’t going nowhere,” he said.

Grist / Katie Myers

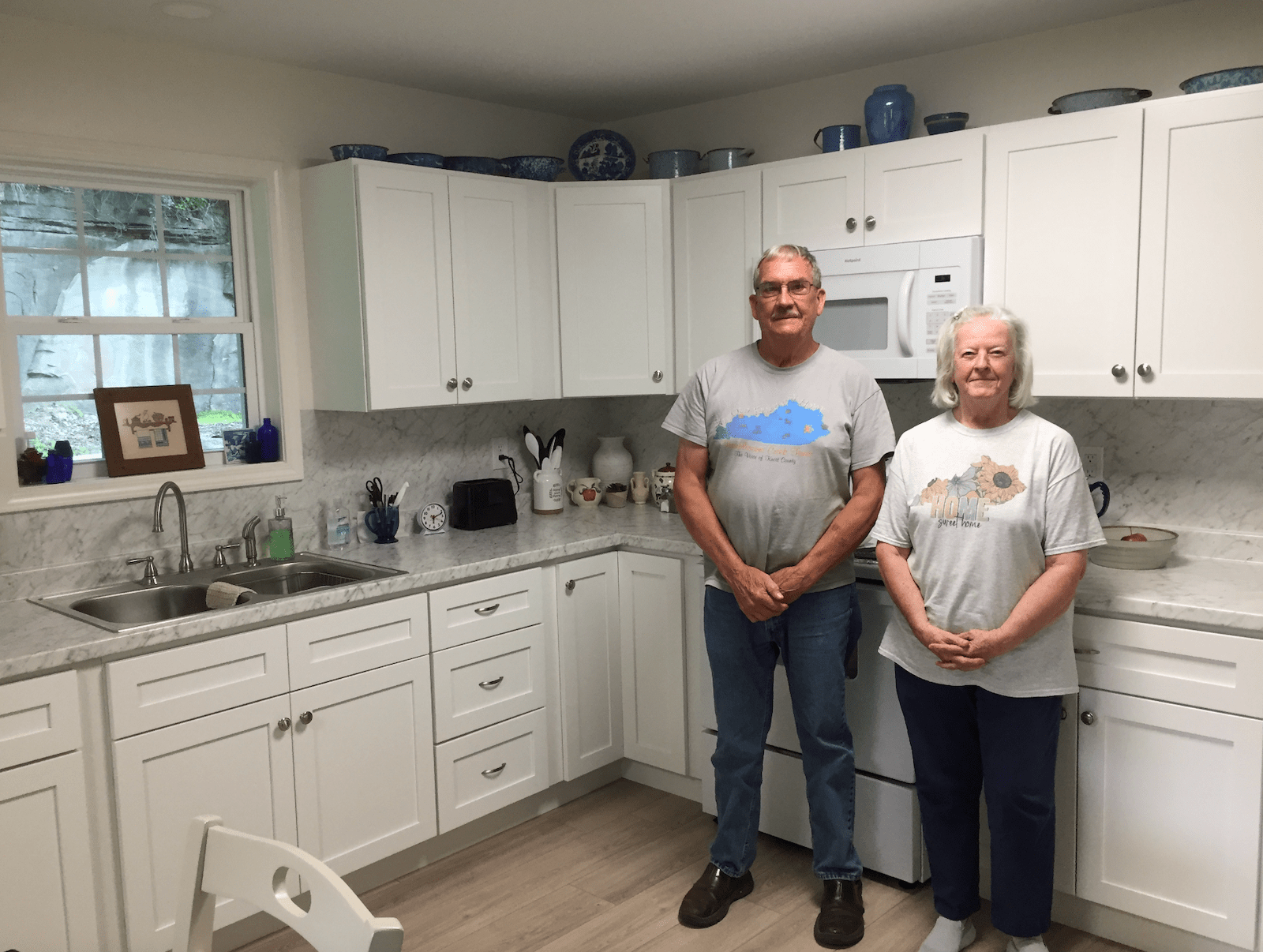

Some folks, through persistence, hard work, and a bit of luck, have moved into new homes.

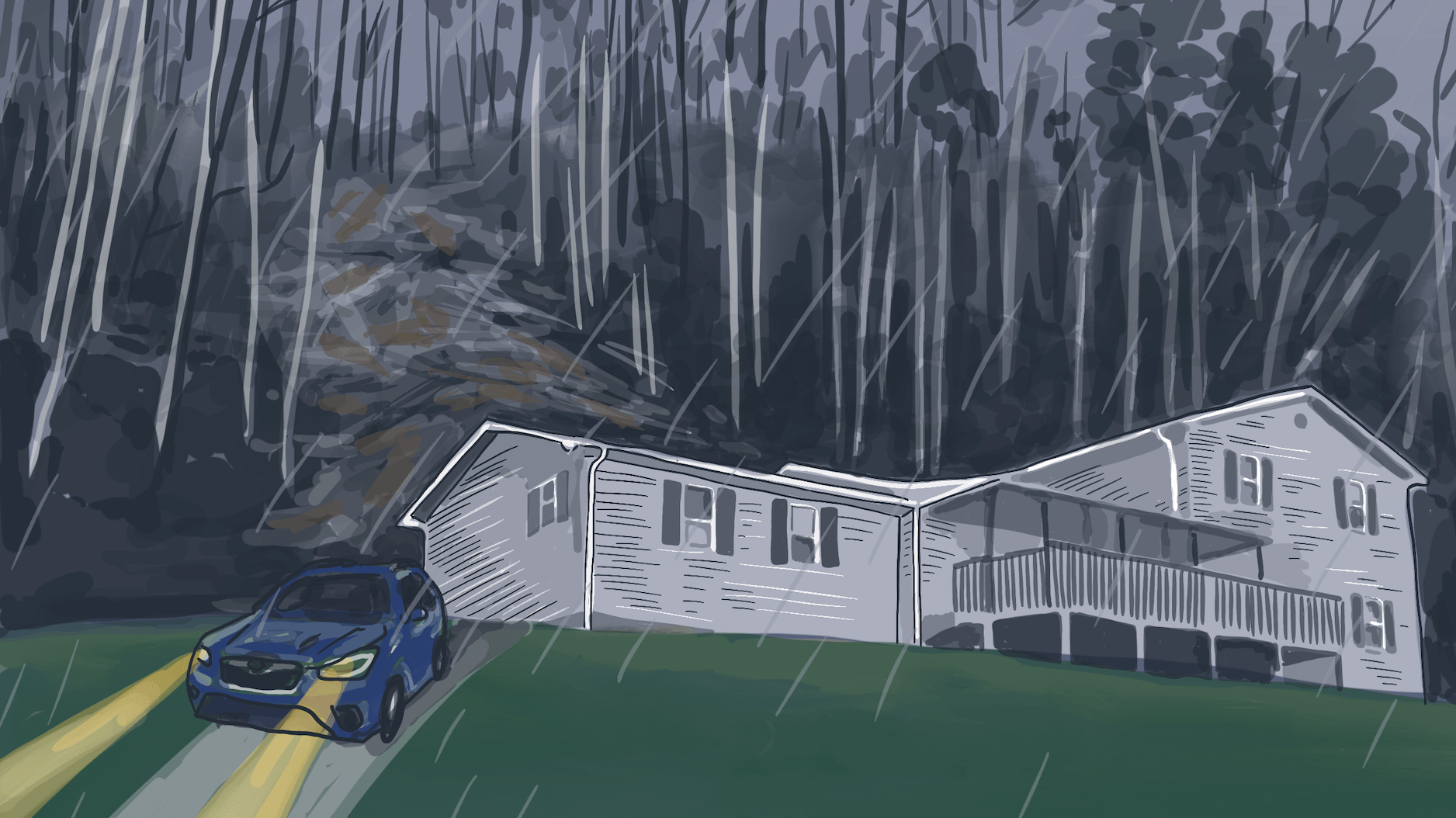

Linda and Danny Smith got theirs from Christian Aid Ministries, a Mennonite disaster relief group, though construction started a couple months later than planned because it ended up taking awhile to figure out exactly where the floodplain was. It was built on their land at the end of a Knott County road called, whimsically, Star Wars Way. According to the Smiths, the group, which was from out of state, nearly ran out of time before having to return home and only just finished the job before leaving. They left so quickly that Danny Smith said he still needed to paint the doors. He isn’t complaining, though. Other homes were left half-done, their new owners left searching high and low for someone to finish the job.

Although grateful for the help that put a roof over his head, Smith got a little tired of dealing with all the people who came to heal his body, his spirit, and his mind even as he completed mounds of paperwork and made calls to anyone he thought might help. “One guy, he kept insisting that I needed to go talk to someone,” he recalled. “And I said ‘who?’”

The man suggested that Danny talk to a therapist. He laughed at the recollection. It was a laugh heard often around here, the sound of a tired survivor who’s already assessed their own hierarchy of needs many times over. “I said, ‘You know, I don’t need nothing done with my mind. I need a home.”

Despite the frustration, the Smiths are piecing their lives back together, a little bit higher up off the ground than they were before. Christine White is praying for a similar outcome, and thinks she can finally see it on the horizon. The occasional nightmare aside, she’s felt pretty good these days.

FEMA gave her $1,900 awhile back to demolish her house and closed her case, leaving her high and dry. She called housing organization after housing organization until CORE, a national nonprofit that assists underserved communities, agreed to build a small home on a piece of land she owns in Floyd County. Construction began earlier this month. White, who spends her time volunteering at a local food bank, calls it a miracle. “You just gotta go where the Lord leads you,” she says. But it’s not built yet, so she’s trying not to count her chickens.

Parker Hobson contributed to this story.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Old nightmares and new dreams mark the year since Kentucky’s devastating flood on Jul 27, 2023.