Imagine 2200, Grist’s climate fiction initiative, publishes stories that envision the next 180 years of equitable climate progress, imagining intersectional worlds of abundance, adaptation, reform, and hope.

[Sign up to receive new Imagine stories when they publish]

1963

Breakfast is interrupted by a crash that shakes the house to its foundations. Out the window, the wet coastal view is obscured by a spray of dust and foam. Another house has slid into the sea.

The silence that floods back in its wake is emptier, the gulls have fled. I wait a minute to see if the drama has roused Nyx, but it is 7 a.m. and she is a teenager, it takes more than the decline of empires to get her up this early. Alone, I step out onto the porch to see the damage.

On our side of Caldwell Street, tight fences enclose narrow two-story townhouses. The remaining houses across the street are shells — condemned and then burnt out by vagrants, eroding into the sea below. A fresh gap has opened up in the row, giving us a view of the rain-speckled waves sucking away tile and plasterboard.

A bell tinkles, drawing my attention to a figure cycling through the long shadows of the condemned homes. She’s a delivery girl, with flat-cap and all, and although it has been at least twenty-five years since the news went online, something in me still responds to the arc of her arm and the thud as a newspaper bounces end-over-end into our porch. Flashbacks to smoothing out the front pages in the dappled sunlight of my parent’s kitchen table. The girl cycles away down the coast road. I rotate the cylinder at my feet with a foot until the masthead comes into view. THE PAST TIMES, bracketed by dodos statant.

“Nyx!” I shout. “It’s for you!”

No reply, unsurprisingly. I hold the bundle to my face and take a nostalgic sniff of newsprint, then deposit it in front of Nyx’s bedroom door, where a poster of a glowering James Dean guards against forceful entry. I return to my breakfast and am scrolling through news about power-failures in India when a scream peals out from upstairs.

Parenting instincts kick in, and I’ve burst past James before I’ve fully registered the situation. Nyx is sitting at the edge of her bed with her arms clasped protectively around her torso. “No, no,” she moans. At her feet is the unfolded PAST TIMES. ‘President’s Death Mourned by World’ reads the headline, above a photograph of the square jaw and Ken-Doll haircut.

Nyx is fourteen, hugging has become complicated. I settle for an awkward arm about her shoulders, side by side so we don’t have to make eye contact. Instead I look around the room — this isn’t a place I’m often allowed these days. Last time I was here there was a bedside table photo frame of Nyx, me, and her mum, but it’s gone now, replaced by a rotary dial phone and a stack of yellow paperbacks with crumbling covers.

Nyx grabs a clunky remote from her bedside table and points it at the boxy screen in the corner. A white line cuts horizontally across the glass then expands into monochrome television footage, darkened at the corners like a fishbowl. A newscaster in a narrow tie is fiddling with his heavy-rimmed glasses as he recounts the news. “ … Dead of an assassin’s bullet, in the 46th year of his life, and in the third year of his, uh, administration as President of the United States.”

“I can’t believe it,” Nyx says, hand over her mouth.

“Surely you knew about this?”

“How would I know about this?” she snaps, shrugging off my arm.

By picking up a book, I think, but have the self-preservation not to say. She’s weeping now. I’m not clear the extent to which this is a joke, I feel like the straight man in a black comedy. But that’s how single parenting has felt like for years.

“Nyxie, this is ridiculous. You never knew him.”

“You never knew Barack Obama, that didn’t stop you crying when all those kids danced at his funeral.”

“That’s different, he’d actually just died.”

“No, he’d died days before. You’d only just found out.”

“…shot apparently from a, uh, warehouse building,” says the dazed newscaster, recounting the President’s final moments. I want to turn the television off, but I’ve forgotten how to operate anything that isn’t voice activated. “Okay, this is stupid,” I say, rising to go. “Breakfast is downstairs when you’re ready.”

“You’re a robot,” Nyx yells. “Don’t you get what it feels like? He was our last hope!”

I close the door behind me to deprive her the option of slamming it, then go into the front garden to call Emily, my colleague at Sustenance Logistics. I’ve known Emily since college and she has her own teenager, so she gets the situation.

Emily answers from her kitchen bench, where she is squeezing vitaworm powder onto a green salad. In the background, I can see her daughter Maeve trudge through the kitchen in a beige dress and pillbox hat, tears glistening on her cheek. Maeve studies drama.

“Ask not what your daughter can do for you, but what you can do for your daughter,” says Emily by way of greetings.

“You too?” I say.

“Apparently it’s Kennedy Day, she says. “What can you do? Just ride it out.”

“Adolescence or history?”

“Both.”

* * *

1969

Winter brings drought, and we lose a lot of the spring wheat harvest. That means we’re competing with the Europeans for the southern hemisphere crop, and I spend my days trying to find out what bribes the French are offering the Australians so that we can match them. The best thing you can say about this summer is that at least the music blaring out from Nyx’s room is good — she’s discovered Jimi Hendrix and Joni Mitchell.

After a bruising six-hour meeting about marketing plankton burgers — ‘give the whole family a whale of a time’ — I come home to find the living room stinking of burnt honey, which is fitting since Nyx has her hair up in a beehive. Nyx is always redecorating the house to keep up with the times. Today she’s commandeered the 3D printer to make retro egg chairs out of cornstarch and hasn’t bothered to open the windows.

“I’m having a moon landing party on Sunday,” she says by way of greeting.

“Is that a request or are you just informing me?” I ask. She doesn’t deign to answer.

I try sitting in one of the egg chairs. It’s still warm, and strands of plastic stick to the back of my pants. “How are you already up to the moon landing?” I ask, trying to show an interest.

“We don’t go literally day-by-day. We fast forward through the slow bits.”

“Who decides what’s slow?”

“The Pacesetters,” she says impatiently, as if it’s obvious.

On Sunday, Nyx is wearing a short red polka-dot dress that I recognised from her mum’s closet — and it had been a vintage item when we bought it. Beneath her back-combed bouffant, she’s starting to look so much like her mum it makes my heart ache.

Nyx isn’t the only one accelerating through time. They come as promised, half a dozen awkward young men and women who were children only yesterday. Now their spotty faces are framed by bowl cuts or hair flips and their skinny ankles stick out from bell-bottom jeans. Maeve is there, and there’s a new face too, a gaunt boy called Kaiden who apparently joined Nyx’s recap group after they used a hunger strike to win the right to attend school assemblies in period dress. It’s abundantly clear from his mournful stares that he wants to have sex with my daughter, less clear whether she realizes, and least clear at all whether I should make some comment to her about it.

The teens gather in the kitchen, windows open to let in the salt air. Outside the street looks like some kind of before-and-after picture of urban renewal, or decay, depending which way you look at it, but the kids aren’t looking at it at all. They’re bent over an old cookery book, laughing over a recipe for meatloaf. The microwave and smart speaker have been politely packed away, replaced with a transistor radio that alternates between rock and roll and crackling updates of Apollo 11’s journey through space.

I’ve invited Emily for moral support, and I raid the fridge to get us drinks. “Do you guys want a couple of beers?” I ask the teens, playing the cool dad. They stare back at me in horror and shake their heads. “Sorry about my dad,” Nyx says as I beat a hasty retreat to the office.

“How did our children turn into our parents?” I say, sitting back down and handing Emily a beer across the table.

“We banned screen-time and told them not to make the same mistakes that we did,” says Emily. “I guess they took it to heart.”

Emily and I are working overtime to finish a policy proposal for the new Minister for Food Security. We discuss the practicalities of commandeering urban roof-gardens as vegetable patches while the kids twist and shout on the linoleum they’ve laid over my Baltic pine floor. When I return for refills, Nyx and Maeve have gone to the bathroom and left Kaiden loitering awkwardly at the kitchen counter. When I was sixteen I would have buried my attention into a smartphone, but of course he doesn’t have one, so he just makes a close study of the fruit bowl.

I look him up and down. He’s done his best with flared jeans and a plaid shirt. I’d say he’s missed the target date by a couple of years, but who am I to judge? I wonder whether to treat him as a boy or an adult, and settle for a conspiratorial man-to-man tone.

“You really into this, then? Recapping?”

“It’s cool I guess,” he says, bending all his attention to fiddling with a pear. “Nyx really cares.”

“It’s been a tough few years for our family,” I say. “It makes sense she wants to live in the past.” I have a sudden urge to unburden myself to this nervous youth, the only other person in the world who rates my daughter as highly as she deserves, but he avoids eye contact as he bends over the grapes. Nyx comes into the room and freezes as she sees us in conversation. “Dad, do you want to come watch the moon landing?” she asks, hastily.

“No, don’t worry about us,” I say automatically, but Emily shouts from the next room, “of course we do!”

“Groovy. But no spoilers!”

We assemble in front of the boxy television. “Let the old folks through,” Emily calls, we cram ourselves into the misshapen egg chairs and accept plates of quivering gelatin. Most of the kids are sitting or kneeling on the floor, reverting to the habits of prepubescence.

I’d vaguely remembered the moon landing as something that occurred in black and white, but the newscaster is in wavering color this time, against a painted backdrop of stars. Between his comments the footage cuts to shots of people watching around the world. With the low picture quality, I can’t tell if the hundreds of New Yorkers standing in a wet Times Square are ghosts from sixty years ago or recappers mimicking them right now.

The kids are tense. “The module’s going to blow up,” Kaiden is saying. “They made an old movie about it, with Tom Hanks.” A wave of silent disapproval emanates from the others. As I’ve learned after many tellings off, it’s taboo to be a “Cassie” and reference anything that happened in the past, now that they’ve decided it’s the future.

The camera cuts to an aluminum and gold spacecraft lander on a gray pockmarked desert, men’s voices crackle incomprehensibly to each other. A figure in a bulky spacesuit kneels at the top of the launcher ladder, like a kid struggling to force herself off a diving board. The picture quality seems too good to be from the 1960s.

“This isn’t real, it’s a simulation,” I say.

Nyx groans. “Oh my God, Dad, you really think this is being faked?”

“No, I mean this footage isn’t from the moon. The programme is demonstrating what is happening in a studio, matched to the audio feed.”

The Neil Armstrong who is not Neil Armstrong is descending the ladder now, a tether being played out for him. The kids look confused.

“So they’re recreating what’s happening at the same time it’s really happening?” asks Maeve.

“Yes. Well no, because there’s nothing really happening on the Moon right now,” I point out.

“You mean the two second time lag?”

“I mean the seventy year time lag.”

“What difference does it make if it’s simulated, it’s real enough for right now,” says Emily, ending the discussion.

Real or not, I’ve never watched this before and my hands start to clench with excitement as the monotonous voice of Mission Control guides Armstrong out of the lander. At the moment the studio footage cuts to a black and white smear with LIVE FROM THE SURFACE OF THE MOON emblazoned below, I join the room in a gasp and glance involuntarily out the window, where a subtle daylight crescent can be seen hanging low in the sky.

“There’s a foot going down, there’s a foot coming down the steps!” cries the newsreader. “If he’s testing that first step, he must be stepping down on the moon at this point.”

“I’m at the foot of the ladder … ” crackles Armstrong. We might as well be looking at smoke, but we all lean forward, straining to make out Armstrong’s boot. He drops to the surface.

“Armstrong is on the moon!” says the off-camera newsreader. “A thirty-eight year old American, standing on the surface of the moon, on this July twentieth, nineteen-hundred-and-sixty-nine.”

The room erupts in cheers and drowns his next words, Emily squeezes my hand. The kids are embracing each other, they don’t care that the man they’re watching is long in his grave, only that we’ve achieved something magnificent. “We’re going to remember this for the rest of our lives,” says Maeve, tears in her eyes. As the tumult dies, Kaiden tries to kiss Nyx on the cheek, she recoils, and the two flounder in awkwardness. The newscaster is saying, “Was that ‘one small step for man?’ I didn’t get the second phrase.”

The coverage rolls on, and for a few minutes I forget about plankton burgers and bushfires, I am overwhelmed by the wonder of something that, up until now, I have always taken for granted. I squeeze Nyx’s shoulder. “Thank you,” I say, and she flashes me a grin.

“Time just stopped for me, and I think it stopped for everybody,” says someone on the television. The coverage is back in the television studio, where the newscaster is speaking to some old science-fiction writer with a combover called Clarke. I tune into what he is saying: “This is the beginning. In the next ten years you’re going to have the establishment of manned orbiting stations, space labs and factories, and simultaneously the development of the first semi-permanent and permanent bases on the moon. Both these things are going to happen in the next ten years, probably the next five.”

“Dad, are you alright?” Nyx asks. Everyone is looking at me, and I realize I am crying. I remember being not much older than Nyx, watching the Mars Curiosity mission unfold on my laptop and thinking that ‘this was the beginning’ of a new era of hope.

It wasn’t, of course.

* * *

1972

There are anti-war roleplayers holding up traffic in the street outside the State House. The air is heady with the smell of weed — the teens are lucky that the police aren’t re-enacting primitive drug laws. “We’re mad as hell and we’re not going to take it anymore!” shouts a kohl-eyed girl from the steps, fist raised.

I get off my bike and try push it through the crowd, but the press of bodies gradually forces me back. Propelled to the edge of the street, I recognise Kaiden in the crowd. He’s shrugged off any remnants of the 21st century and he sports his kaftan as just another outfit now, not a costume. He’s wearing a peace patch on his arm.

“Who is this for? There’s no goddamn war in Vietnam.”

“It’s a metaphor!” he shouts back.

“For what?”

He shrugs, makes a half-gesture that takes in the barbed wire around the state capitol, the dead trees in the municipal gardens, the police drones hovering overhead. “Everything!” he says.

The teens on the steps are arm in arm now, singing “A Change is Gonna Come.” “Get a job, hippies!” I snarl in my best Richard Nixon impression, then turn my bike around. I guess I’ll be working from home today.

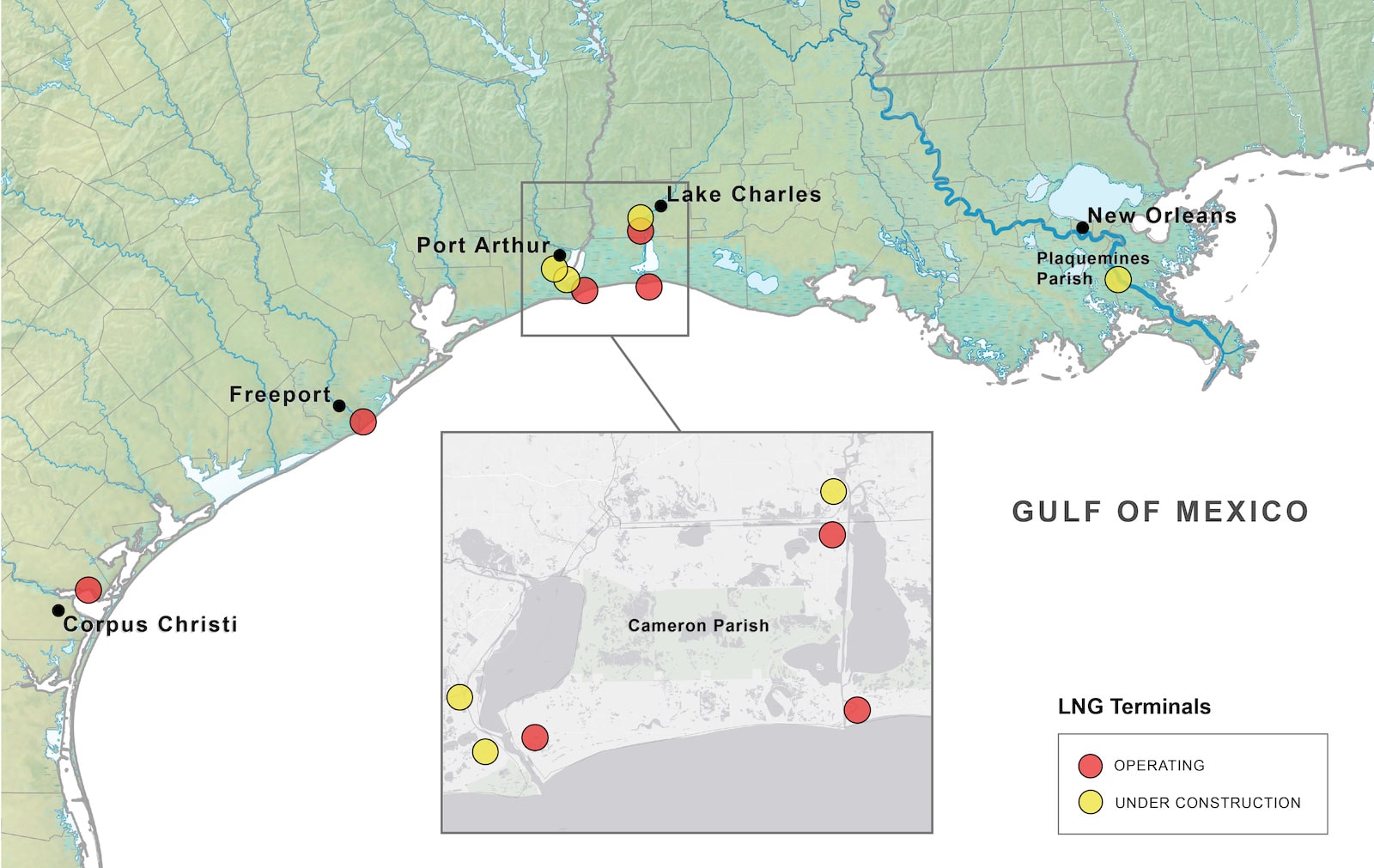

I can’t bear the living room, since Nyx redecorated it in orange and umber shades, so I set up my workstation at the kitchen counter and flip through a glossy government report about fish stocks in the Gulf of Mexico. Its findings, wrapped in soothingly neutral language like cotton wool, make me feel like my ribs are crushing my heart. To distract myself, I brood on the rally. I realize that it’s been months since I’ve seen a teenager not dressed in the fashions of yesteryear. How far has this game spread?

Nyx’s friends feigned ignorance whenever the Internet was mentioned, but their little subculture couldn’t exist without it. A few clicks take me to an ASCII-text bulletin board that looks as primitive as can be without sacrificing all functionality. A clock at the top of the screen informs me that today is April 22, 1972.

The jargon is a mix of archaic and contemporary slang and I don’t understand the acronyms, but what’s clear is the scale of the operation. Hundreds of thousands of discussions, overseen by a global network of ‘Pacesetters’ who massage the calendar.

> March ’75 is bones, can we jump straight to Fall of Saigon, or problems for ILK? 10-4.

Adolescents exulting in their creativity. They’re so damn smart, and they’re wasting their lives.

It makes me so angry.

I’m not surprised when Nyx comes in at lunchtime. She’s wearing one of my green jackets that hangs down to her thighs, a blue badge pinned to the lapel reading McGovern ’72, and it’s clear she hasn’t been to class. She gives me the most cursory of greetings and starts burrowing through the pantry.

“There’s no real food,” she says petulantly. “Your whole job is the acquisition of food. Why don’t we have food?”

“There’s plenty of food.”

She sifts through potatoes with a world-weary expression. “Why can’t we have hamburgers for once? I could cook them.”

“Because beef costs $40 a pound. Why aren’t you at school?”

“School’s full of spoilers. Besides, don’t you know there’s a war on?”

“You realize we have a cousin in Vietnam? Stephen, he runs a brewery on the Mekong. I promise you nobody is dropping bombs on him.”

She’s munching a biscuit now, she doesn’t respond.

“So you’re just skipping classes now? Have you thought about college?”

“It stresses me out, thinking about the future,” she says, not making eye contact. “Anyway, not to be a Cassie, but personal computers will be coming in the ’80s, so maybe I’ll just teach myself programming and catch the wave.”

“You can’t get a job for a world that doesn’t exist.”

“Big words from the guy with a philosophy degree,” she says, and tries to edge past me to the living room.

“OK boomer,” I say, standing up and ready for a fight. I bar her way and tap the McGovern badge. “How long are you going to live like this? Do you even know who the President is?”

“Tricky Dick,” she says defiantly. Her shoulders are hunched forward now, her breathing quickening.

I rustle through my workstation, grab A REPORT ON A SCIENTIFIC SURVEY OF ADULT FISH STOCKS IN THE GULF OF MEXICO and thrust it under her nose. “Do you know what’s happening in the real world? 45% of fish, gone in a decade.”

“Spoilers,” she says, closing her eyes.

“It’s not spoilers, it’s spoiled!”

“What do you want me to say about this?” she says in a cold, choked voice that I’ve never heard from her before. “I can’t do anything about the fish. Why does it bother you so much that we’re trying to have some fun?”

I slam the table. “Because these people you worship, they’re the ones who fucked it up! They made great music and great movies and then they set fire to the planet. I’m going to spend the rest of my life picking up the mess they dumped on us, and you’re checking out on me?”

“So why didn’t you fix it when you had the chance? You can’t blame me for the world!” she shouts, slipping under my arm. Fisheries pamphlets raised like the tablets of Moses, I pursue her across the shag carpet of the living room and up the stairs, aware of how absurd I must look and too angry to care. She slams James Dean in my face, but I’m not having it this time. I force the door open again as she is scrabbling with the lock and she stumbles back towards her bed, shocked at the violence of my incursion.

“You can’t spend the rest of your life hiding … ” I shout, pressing forward.

I stop, suddenly dizzy. My perception feels off, like I’m ten feet tall. I lean against the door jamb in confusion and take in what I am seeing.

We’re standing in my childhood bedroom.

There’s my Lego pirate ship on the windowsill. The lampshade ringed with dancing clowns. My name, spelled out in luminescent plastic stars stuck to the walls, which are painted in the pastel green I remember. The only anachronisms are the 3D printer in the corner and the photo of me, Nyx, and her mum, returned to its place by the bed. Otherwise, it’s exactly as I remember at the moment I moved away when I was 12. I’ve never seen it from an adult height before.

“I wasn’t going to show it to you until your birthday,” says Nyx. “I mean your actual birthday, in 1986.”

I finger a poster of Britney Spears on the wall, as glossy as if it were torn from Rolling Stone yesterday. “Where did you get all this stuff?”

“Printed it,” she says. “I recreated it from those old movies you have in the attic. We’re not supposed to use camcorders yet, but I needed to get a head start.”

I open the shutters, half-expecting to see the swing my father made, hanging from a branch of the peppercorn tree. Instead there is the ocean view, the stumps of coastal houses like broken teeth. I sink onto my Simpsons comforter, overwhelmed by the flow of time. When I close my eyes, I can almost hear the comforting sound of my parents laughing from the end of the hall.

I can hear them. Nyx is playing some ambient sound sample — looping dialogue from my parents, pitched at a nearly inaudible murmur, as if they were hosting a party downstairs. I scrunch the sheets in my hand and fall through memories.

“You’re so stressed all the time.” Nyx’s voice floats to me from the real world. “I’ve never known anyone as stressed as you. I thought this could be, like, a safe place for you.”

“I don’t want this, Nyx.”

“I don’t understand what you do want. You, Maeve’s mum, my teachers, you’re just counting crumbs all the time. I don’t want that. I don’t want to live like that.”

“I’m sorry,” I say, as my leg starts to tremble. “I’m sorry we made a world you don’t want to live in. I’m sorry we weren’t able to fix it. We tried.”

She comes over and, for the first time in two years, wraps her arms around me. For a moment we sit and hold each other on the Simpson’s bed, my dead mother’s laugh echoing down the hall.

“Please don’t leave me in this century alone,” I whisper into her hair.

* * *

1981

CONGRATULATIONS CLASS OF 1981 reads the banner hanging in the sports hall. The school has completely given up on any kind of temporal dress code and there isn’t a student on the stage who isn’t rocking their grandparent’s stylings as they accept their diploma.

Emily and I clap with bemusement, we clap with confusion, but most of all we clap with love and pride. The valedictorian says her greatest wish is that her generation might grow up without fear of the Bomb and then fixes the audience with a meaningful look. I wonder if it’s a metaphor, but I’ve long learned the futility of trying to penetrate the kayfabe of the recappers.

After the ceremony, Emily and I bite back our laughter as we congratulate our anachronistic offspring. To our surprise, they ask if we want to join them for a victory lap of the town. We walk in the sun together along the beach, strolling after our shadows. Maeve is in a bridal gown defaced by her classmates signatures, Nyx has feathered her hair and squeezed herself into a pair of high-waisted white jeans. Kaiden’s there too, as he usually is these days, arm slung around Nyx. His shoulders are not quite big enough for the musty-smelling sports blazer he’s dug out of some charity bin.

“So, how’s morning in Reagan’s America?” I ask.

The kids exchange glances and laugh. “Reagan?” asks Nyx. “He’s a has-been. Carter smashed him.”

I nod automatically, then start. “Wait, what? Carter didn’t win the 1980 election.”

“Well, we all voted, and Carter swept every state,” says Maeve. “If you wanted Reagan so bad you should have voted for him.”

“That’s not how it happened!” Emily says.

“Things were starting to get pretty grim there after the oil crisis,” says Nyx. “I guess we just kind of discussed it on the boards, and the Pacesetters decided it was okay to make some changes. Just because it went wrong once, doesn’t mean it has to always be wrong.”

I want to press them, but the kids are not interested in this conversation. Federal politics are far away and this is their day of freedom. They demand ‘real food,’ and we buy them the biggest, most expensive ice creams in town. “So, what are you gonna do with your life?” I ask, once we are all licking our cones.

Kaiden and Nyx exchange glances, open their mouths at the same time, then falter with a laugh. He gestures to her, and she says, “Actually, we’re planning to take a ship to China next year. A whole bunch of us have been invited as foreign reps to the 12th National Party Congress in 1982.”

I laugh, then realize that they’re not joking. “What do you mean? What government do you represent? You don’t represent anything.”

“It’s a recap conference. The Soviets will be there too. Acid rain and the Greenhouse Effect are becoming a legit problem, you know, Dad? So we’re going to sort it.”

Her eyes twinkle at me, but she doesn’t break character.

I’m stunned. “Wait, who’s paying for this ‘trip to China?’” I say.

But Nyx, Kaiden, and Maeve have lost interest, they’re taking Polaroid shots of each other in “thoughtful” poses, white photos fluttering down to white sand. They run into the surf, fully clothed, and shriek as the waves wash against their knees. Above them the patrolling drones buzz across the sky, guarding against sharks and refugees, but the kids only have eyes for each other.

They’ve left their pocket radio in the sand, and from its little speaker Cyndi Lauper’s breathless vocals burst out onto the beach. Nyx runs back from the surf, grabs me round the shoulders, blinds us with a Polaroid shot, and all the while the radio sings that “Girls Just Want to Have Fun.”

“I’m sure this song didn’t come out until 1983 at least,” I protest.

“So?”

“Well what about the, I don’t know, space-time continuum?”

“My God, you sound old,” my daughter says, and takes a lick of my pistachio ice cream.

Learn more about Grist’s Imagine 2200 climate fiction initiative. Or check out another recent Editors’ Pick:

Jack Nicholls is a British-Australian writer based in Melbourne. Their speculative fiction has been published in a variety of anthologies and internet corners, including at Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Aurealis and Tor.com.

Mikyung Lee is an illustrator and animator in Seoul, South Korea. Her poetic and emotional visual essays focus on the relationships between people and objects, situations, and space.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Imagine 2200: Replay Boomer | Climate Fiction on Aug 3, 2023.