Over 1 trillion LEGO bricks have been manufactured since the mid-1950s when the company began…

The post Recycling LEGO Bricks: A Sustainable Solution From Brick Recycler appeared first on Earth911.

Over 1 trillion LEGO bricks have been manufactured since the mid-1950s when the company began…

The post Recycling LEGO Bricks: A Sustainable Solution From Brick Recycler appeared first on Earth911.

Tune in to a special Earth Day 2024 episode about accelerating the path to a…

The post Earth911 Podcast: Mapping A Smart Path To The Circular Economy At The Ellen MacArthur Foundation REMADE Conference appeared first on Earth911.

This story is published as part of the Global Indigenous Affairs Desk, an Indigenous-led collaboration between Grist, High Country News, ICT, Mongabay, Native News Online, and APTN.

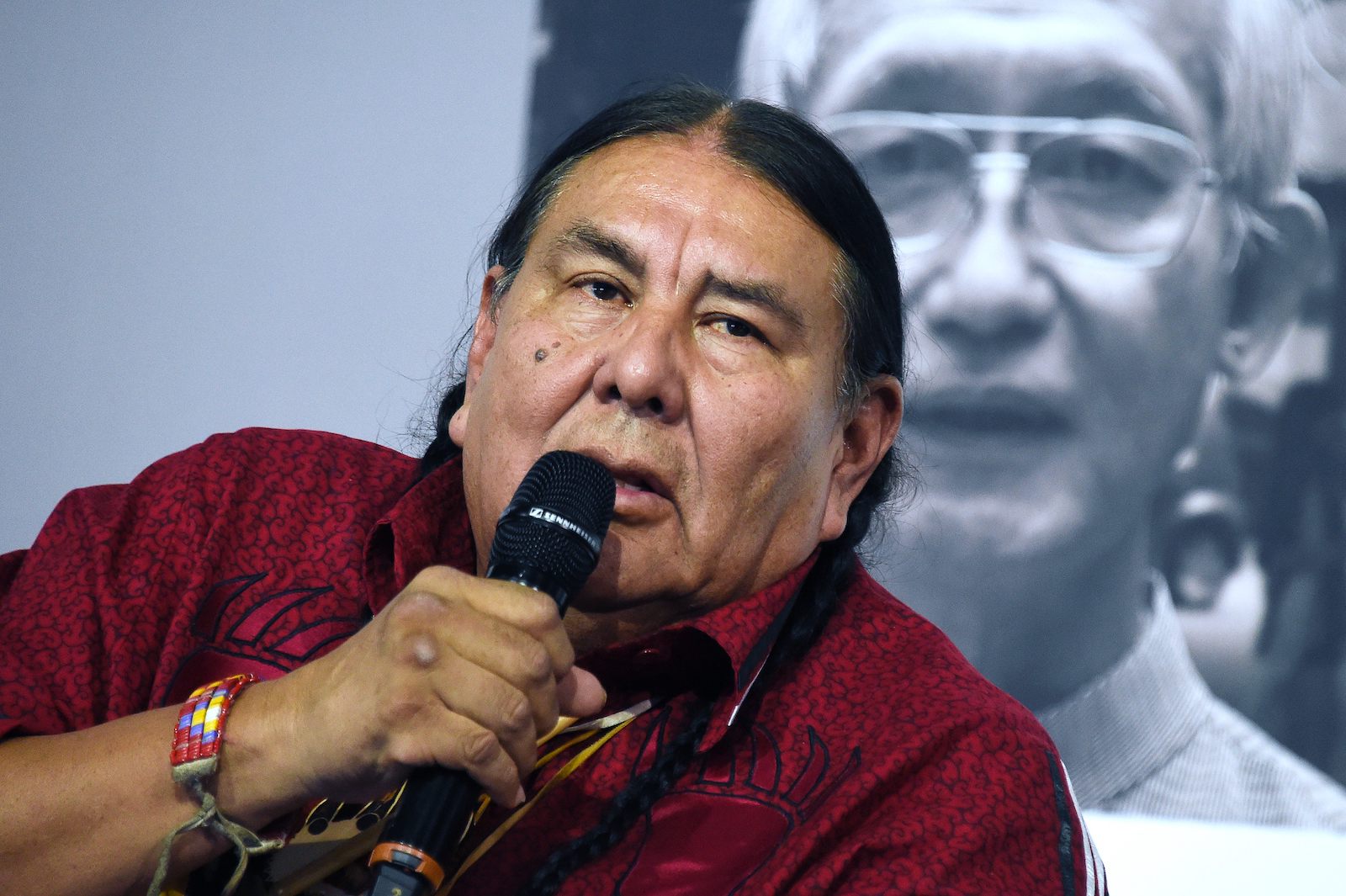

For more than 20 years, Tom Goldtooth has listened to conversations about the negative impacts fossil fuels and carbon markets have on Indigenous peoples. On Wednesday, Goldtooth and the Indigenous Environmental Network, or IEN, called for a permanent end to carbon markets. Beyond being an ineffective tool for mitigating climate change, the organization argues; they harm, exploit, and divide Native communities around the world.

The recommendation was delivered to a crowd of Indigenous activists, policymakers, and leaders at the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, or UNPFII, and is the most comprehensive moratorium on the issue the panel has ever heard. If adopted, the position would pressure other United Nations agencies — like the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change, or UNFCCC — to take a similar stance. The heightened urgency stems from the COP29 gathering planned later this year, when provisions in the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement on carbon market structures are expected to be finalized.

“We are long overdue for a moratorium on false climate solutions like carbon markets,” said Goldtooth, who is Diné and Dakota and executive director of IEN. “It’s a life and death situation with our people related to the mitigation solutions that are being negotiated, especially under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. Article 6 is all about carbon markets, which is a smokescreen, which is a loophole [that keeps] fossil fuel polluters from agreeing to phase out carbon.”

The Network’s language on “false climate solutions” is intentional. Tamra Gilbertson, the organization’s climate justice program coordinator and researcher, said a false climate solution is anything that looks like a tool for reducing emissions or fighting climate change but allows extractive companies to continue profiting from the fossil fuels driving the crisis.

“Carbon markets have been set up by the polluting industries,” Gilbertson said. “The premise of carbon markets as a good mitigation outcome or a good mitigation program for the UNFCCC is in and of itself a flawed concept. And we know that because of who’s put it together.”

The carbon market moratorium the Network called for would end carbon dioxide removal projects like carbon capture and storage; forest, soil, and ocean offsets; nature-based solutions; debt-for-nature swaps; biodiversity offsets, and other geoengineering technologies.

This year’s moratorium recommendation builds on a similar proposal the IEN offered at last year’s Forum, when it called for a stop to carbon markets until Indigenous communities could “thoroughly investigate the impacts and make appropriate demands.” That call led to an international meeting in January, where Native experts discussed the impacts a green economy has and would have on their communities. Ultimately, the participants produced a report detailing how green economy projects and initiatives can create a new way to colonize Indigenous Peoples’ lands and territories.

Darío José Mejía Montalvo, of the Zenú tribe in Colombia, participated in the January meeting and has chaired a previous UNPFII. He highlighted the report during a UN session last week.

“The transition towards a green economy [keeps] starting from the same extractivist-based logic that prioritizes the private sector, which is guided by national economic interests of multinationals, which ignores the fights of Indigenous people, the fight against climate change, and the fight against poverty,” Montalvo said, according to a UN translation of a speech he delivered in Spanish.

Goldtooth and Gilbertson say that, while the January report established wider consensus around the negative impacts of the green economy, the IEN felt that the report’s recommendations were unclear and did not go far enough to discourage the growth of carbon markets – which is why the organization is calling for a permanent moratorium.

“We have to do everything that we can from every direction we possibly can in this climate emergency that we’re in, because we don’t have a lot more time,” Gilbertson said. If carbon markets are enshrined in Article 6 of the Paris Agreement as they are currently written and become a more powerful international network, “we are in a whole new era of linked-up global carbon markets like we’ve never seen before. And then we’re stuck with it.”

Under the Paris Agreement, countries submit plans detailing how they will reduce emissions or increase carbon sequestration. Article 6 provides pathways for nations to cooperate on a voluntary basis and trade emissions to achieve their climate goals. More specifically, paragraph 6.4 would create a centralized market and lead to large-scale implementation of emission reductions trading. The nuances of these structures and how carbon markets are presented in Article 6 has far-reaching impacts: A report released in November by the International Emissions Trading Association, or IETA, showed that 80 percent of all countries indicate they will or would use carbon markets to meet their climate goals.

In its current form, carbon offset projects as described in Article 6 of the Paris Agreement would further threaten Indigenous land tenure and access to resources. If finalized in November, pilot projects are expected to start as soon as January 2025.

At this year’s Forum, organizations like the United Nations Development Program, Climate Focus, Forests Peoples Programme, and Rainforest US discussed new initiatives to protect Indigenous peoples’ rights within a carbon market. In particular, there’s increased attention on policies that would more effectively incorporate free, prior, and informed consent, or FPIC, into carbon offset operations. But Kimaren Riamit, executive director of ILEPA-Kenya, an Indigenous-led nonprofit, said the foundation that must be established even before FPIC is better recognized Indigenous self-determination – agency for tribes to decide for themselves if they want to engage in carbon market projects at all.

“FPIC without enablers of self determination is useless because what do you give consent over when your land rights are not there? What do you give consent of if you are not part of the decision governance arrangement?” said Riamit, who is of the Maasai tribe in Kenya. Enablers of self-determination include protections for Indigenous land sovereignty and land tenure security.

Riamit says that, in carbon market projects, free, prior, and informed consent has become a strategic tool and a confusing exercise in disseminating information rather than a way of obtaining meaningful consent from tribes. There must be a deliberate and full disclosure to tribes of what they are agreeing to when engaging in a carbon market project, and time for them to digest the information, consult internally, provide feedback, and – critically – “be able to say no.”

It’s notable to Riamit that carbon offset companies don’t advocate strongly, if at all, for improved self-determination of the Indigenous communities they work with.

“They don’t sharpen a knife to slaughter themselves,” he said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Indigenous peoples rush to stop ‘false climate solutions’ ahead of next international climate meeting on Apr 22, 2024.

This story is published as part of the Global Indigenous Affairs Desk, an Indigenous-led collaboration between Grist, High Country News, ICT, Mongabay, Native News Online, and APTN.

Last week a United States federal judge rejected a request from Indigenous nations to stop SunZia, a $10 billion dollar wind transmission project that would cut through traditional tribal lands in southwestern Arizona.

Amy Juan is a member of the Tohono O’odham nation at the Arizona-Mexico border and brought the news of the federal court’s ruling to New York last week, telling attendees of the the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, or UNPFII, that she was disappointed but not surprised.

“We are not in opposition to what is called ‘green energy,’” she said. “It was the process of how it was done. The project is going through without due process.”

It’s a familiar complaint at Indigenous gatherings such as the one this week, and last, at the U.N., where the general consensus among Indigenous peoples is that decision makers behind green energy projects typically don’t address community concerns.

According to Pattern Energy, the Canadian-owned parent company of SunZia, the wind transmission project is the largest clean energy infrastructure initiative in U.S. history, and will provide power to 3 million Americans, stretching from New Mexico to as far as California.

Now on track to be finished in 2026, the transmission pipeline is a cornerstone of the Biden administration’s transition to green energy.

The 550-mile high-voltage line has a 50-mile long section that cuts through the San Pedro Valley and Indigenous nations that include the Tohono O’odham, Hopi, Zuni and San Carlos Apache.

The suit against the U.S. Bureau of Land Management was filed in January. The lawsuit called the valley “one of the most intact, prehistoric and historical … landscapes in southern Arizona,” and asked the court to issue restraining orders or permanent injunctions to halt construction.

The tribes fear the pipeline will irreversibly damage the land both ecologically and culturally.

The federal court chided the tribes for not filing suit earlier, noting they had a window of six years to file from 2015, when the project was originally approved. “Plaintiffs’ 2024 challenge to the [project] is therefore untimely,” the judge’s decision read.

The tribes had been actively pushing for alternative routes and for more in-depth reviews of the land in question for years. Their argument is that the six-year timeline began last fall, not earlier.

Juan said these miscommunications or differing interpretations of the law can be compounding factors that stand between Indigenous rights and equitable green energy projects.

“There is really no follow through when tribes express their concerns.” she said.

Back at the U.N. the ruling was a reminder that the U.S. doesn’t recognize the tenets of “free, prior and informed consent” as outlined in the U.N. Declaration of Human Rights. Those tenants are meant to insure that Indigenous land isn’t used without input and permission from the Indigenous peoples involved.

Andrea Carmen, who is Yaqui, was at the U.N. forum on behalf of the International Indian Treaty Council, a group that advocates for Indigenous rights around the world. The council is advocating for a moratorium on green energy projects for all U.N. entities “until the rights of Indigenous peoples are respected and recognized.”

“It’s hard to convince governments and businesses to deny these big energy projects without outside intervention,” she said.

“They are doing the same thing as fossil fuel,” she added. “It’s just more trendy.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline A gigantic green energy transmission project will cut through Indigenous lands in the Southwest on Apr 22, 2024.

This story is being co-published with Public Health Watch.

West of the Rockies, just one lead battery recycler remains in the United States. If your car battery conks out in downtown Seattle or the Sonoran desert, it will probably be hauled to Ecobat, a lead smelter half an hour east of downtown Los Angeles.

Ecobat’s facility in City of Industry melts down 600 tons of batteries and scrap every day. A conveyor belt takes the batteries to a hammer mill where they’re cracked open and slammed into pieces. Then a furnace blasts them with 1,000 degrees of heat. The resulting ingots or “pigs” of lead then ride on, to become batteries once again.

Nationally, about 130 million car batteries meet this fate each year. Fewer than a dozen smelters do this work in the U.S. No other consumer product in the country closes its recycling loop so completely.

But the crucial business of smelting lead is also a very dirty one.

Lead is a neurotoxin; no known levels of it are safe. People who breathe airborne particles of lead or accidentally put it in their mouths — especially children — can suffer nerve disorders and developmental problems. The smelting process itself can create a cancer risk. In addition to lead, it can send arsenic, hexavalent chromium, formaldehyde and other chemicals into the air.

California has some of the tightest toxic regulations and strictest air pollution rules for smelters in the country. But some residents of the suburban neighborhoods around Ecobat don’t trust the system to protect them.

Tens of thousands of people live in the bedroom communities of Hacienda Heights, La Puente, and Avocado Heights, including some just hundreds of feet from the edge of the company’s property. Uncertainty, both about the safety of Ecobat’s operation going forward and the legacy of lead it has left behind, weighs heavily on them.

For decades, thousands of pounds of lead poured out of the smelter’s stacks. Soil testing has revealed high levels of lead on some properties over the years, but hasn’t led to a full investigation. Although pollution controls have squashed airborne lead to a fraction of its historical highs, Ecobat — known until recently as Quemetco — has amassed nearly $3 million in regulatory penalties since 2020.

The facility is operating under a permit that expired almost nine years ago. The Department of Toxic Substances Control, or DTSC, which oversees California’s hazardous waste laws, has sent back the company’s application for renewal three times. Once the filing is complete, DTSC will release a draft permit to the public for comment.

But the release date listed on the department’s website keeps shifting — from February, to March, to April, and as of this week, May.

In the meantime, long-brewing disputes among residents, the company, and regulators are again erupting into public view.

Laws don’t mean much, say neighborhood advocates, if nobody enforces them.

“The regulators, they back down,” said Rebecca Overmyer-Velázquez, a coordinator with the Clean Air Coalition of North Whittier & Avocado Heights. “That’s really our biggest problem.”

In recent months, the dispute has taken on more of an edge. Younger activists impatient with the lack of progress are leading their own inquiry into soil contamination. Ecobat is suing the state over decisions related to the facility. Court filings and lawyers’ threats showcase a bitter and growing divide on questions of public health, responsible product management, and environmental safety.

“What they’ve really been denying the community is the ability to really call the question, should this facility, based on its past operation, receive a renewal of its hazardous waste permit?” said Angela Johnson Meszaros, an attorney at Earthjustice, which represents the Clean Air Coalition. “The community’s position is no. And I think that they have the receipts for why the answer is no.”

Ecobat did not make anyone available for an interview. In a written response to questions, Dan Kramer, a spokesman, said the company is “continuously committed” to protecting public health. “Ecobat’s number one priority is safety — for our employees, their families, and the people living and working in the communities surrounding our facility.”

At issue are not only how California protects public health going forward but also what regulators are willing to do about the past.

The Clean Air Coalition’s Overmyer-Velázquez wants her neighborhood to avoid what happened when another lead smelter closed south of downtown Los Angeles. Exide Technologies may have contaminated as many as 10,000 homes in predominantly Latino, working-class neighborhoods. When it abruptly shut down after 90 years, lawmakers and regulators vowed that Exide would pay to clean up neighborhood-level soil contamination. But in 2020 a bankruptcy court allowed the company to abandon the property, and the cleanup remains incomplete. The cost is ballooning, and so far Californians are paying for it.

Overmyer-Velázquez wants the Ecobat facility shut down, or moved away from densely populated Los Angeles County.

“This place has clearly demonstrated it cannot be a good neighbor,” she said.

DTSC did not make anyone available for an interview. In a written statement, a spokesman for the department said that it has made significant improvement to the permitting process, and that a decision on the facility’s permit “will be grounded in the latest scientific evidence regarding the potential impact of Ecobat’s operations on public health and the environment.” DTSC denied that the process has been delayed.

Half a century ago, after the Cuyahoga River burned in Ohio and as New York’s Love Canal raised national alarms about toxic waste, the Golden State was ahead of the game. California was vocal about the need to limit hazardous waste, to handle it safely, and to keep it local, rather than shipping it somewhere else, where laws are weaker. The state set stringent controls on storage and processing and began requiring permits for facilities. The company then called Quemetco filed for its first operating permit — a temporary one — in 1980.

But some of California’s management plans never materialized; some oversight, starved for staffing and funding, fell to shreds. It took 25 years for regulators to grant Quemetco a full hazardous waste permit.

Early on, environmental officials flagged reasons for concern about the lead smelter. State and federal regulators issued an order and a consent decree in 1987 because of the facility’s releases of hazardous waste into soil and water. An assessment from that time found “high potential for air releases of particulates concerning lead.”

It wasn’t illegal back then for Quemetco to send pollution straight into nearby San Jose Creek, or to dump battery waste into the dirt on a corner of the property without any formal containment. In 1987 alone, according to the federal Toxics Release Inventory, Quemetco reported that it had released nearly 4 tons of airborne lead from its stacks. That was okay, too.

By the 1990s, however, the science about lead was piling up, finding that the health hazards of even low levels of exposure were problematic, especially for children.

In the bedroom communities around Quemetco, neighbors took notice. At a public meeting in 1996, they asked why the permitting process was taking so long.

DTSC’s Phil Chandler, a soil geologist who was working on the facility’s permit at the time, answered the crowd. He explained that the delay was understandable.

“There was an awful lot of firms, like Quemetco, they came in the door, and said, ‘We want a permit.’ And they came all at once,” Chandler told residents back then. “So that’s been a problem.”

More people began raising questions about lead-related health impacts.

Jeanie Thiessen, a special education teacher at a public school in the area, wanted her students to be tested for lead exposure. “Many exhibit signs of neuropsychological problems, cognitive impairments, become easily agitated, and have generally arrested development,” she wrote in a DTSC questionnaire. “Surely it is not normal to have so many children with learning disabilities come from so small an area.”

“I grew up with a lot of those kids,” said Duncan McKee, a longtime critic of the facility who lives in Avocado Heights. He says those worries were common. Looking back, he added, “I think at that point [regulators] started taking it a bit more seriously. Maybe.”

When DTSC finally granted Quemetco a permit in 2005, it didn’t end the communities’ concerns about health and safety.

In Los Angeles, lead smelters are overseen by the South Coast Air Quality Management District. It requires large polluters to submit health hazard assessments that calculate potential cancer risks stemming from their emissions. Quemetco’s assessment in 2000 revealed that it had the highest calculated cancer burden in Los Angeles County, not only because of lead, but also because of other carcinogens involved in the process: arsenic, benzene and 1, 3 butadiene.

That health hazard assessment led to tighter pollution controls at the smelter. In 2008, Quemetco installed an advanced air system called a wet electrostatic precipitator, or WESP. Before the scrubber was installed, the additional cancer risk from the facility for people in the surrounding area was 33 in 1 million, well above the threshold at which polluters are required to cut emissions and notify the public. In the company’s next assessment, that risk had dropped to 4 in 1 million.

Today, emissions from the company, now known as Ecobat, are well within South Coast’s smelter-specific lead limit. But regulatory problems at the facility remain stubbornly frequent.

South Coast has written Ecobat up for violations 20 times since 2005. Just four years ago, the agency issued a relatively rare $600,000 fine for failing to meet federal and state-level standards. In a press release, South Coast noted that because of lead exceedances, the facility had to temporarily reduce operations.

During DTSC’s most recent 10-year compliance period for the smelter, 2012-2022, Ecobat accrued 19 violations of the most serious type. On one visit, for example, regulators found cracks in the floor of a battery storage area, where acid, lead, and arsenic could leak. In some cases, according to the state’s online records repository, the facility was out of compliance or violations had been in dispute for years. The state’s lawyers filed a civil complaint based on some of these violations and later settled it for $2.3 million. Ecobat paid half the money to the state and half to nonprofits that promote school health and knowledge of local environmental issues.

In its written response to Public Health Watch, the company characterized “nearly all” of the violations as “technical disagreements between Ecobat and DTSC over environmental monitoring systems in place at the facility.”

“None of the alleged violations involved allegations that Ecobat had improperly handled or released hazardous waste or caused any environmental impacts to the community,” said Kramer.

On its website, Ecobat emphasizes that it “has invested close to $50 million installing and maintaining new pollution control equipment and monitoring devices.” That includes the WESP, which Kramer said “was not necessary to meet Ecobat’s risk reduction obligations or any other regulatory mandates.” Instead, Kramer said, the installation of that scrubber was voluntary, and at significant expense to the company.

Questions remain about where and whether the soil may be contaminated in neighborhoods around Ecobat; how much of the pollution in the soil can be attributed to the smelter; and what, if anything, the company can be forced to clean up.

The facility itself reported to the federal government that its stacks ejected thousands of pounds of lead particulate into air each year through most of the eighties, and hundreds of pounds of airborne lead annually for another couple of decades after that.

Roger Miksad, president and executive director of the Battery Council International, a trade association, argues that it’s often hard to identify the source of lead in an urban environment. The 60 freeway is nearby, for example: gasoline once was leaded, and some brake pads for cars are made with lead. Older paints also contain the toxin.

“The number of other sites, be it from lead paint or anything else, I’m sure are innumerable,” Miksad said. “It’s not [Ecobat’s] responsibility to clean up someone’s underlying mess just because they happen to use the same chemical.”

But to the community and its advocates, tracing the lead is a matter of common sense.

“If you have a range of metals coming out of your stack, and if you have them going into the air, it just falls to the ground,” says Earthjustice’s Johnson Meszaros. “It has to; it’s just basic physics.”

Earlier this year, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency announced that in areas where there are multiple potential sources of lead, screening for further action would begin where the toxin was found at 100 parts per million in soil. California’s screening level is more aggressive: 80 parts per million.

When DTSC sampled more than 50 sites within a mile of Ecobat in the 1990s, it found lead well above both those levels. At one house, lead was measured at 660 parts per million; at another property, sampling found 1,100 parts per million. But nothing more happened until 2016, when DTSC ordered Quemetco to test soils beyond its fenceline for the first time.

The company’s sampling revealed lead exceeding 80 parts per million in soil at most, if not all, of the residential properties visited. The state ordered the company to do more follow-up work, this time testing along lines radiating outward from the facility. Sampling found lead in some areas, but DTSC said the existing sampling plan is “not comprehensive and thereby the findings are not conclusive. Additional sampling is necessary to confirm the extent of facility related impacts in the community.”

At Los Angeles County’s other lead smelter, the now-shuttered Exide plant in Vernon, soil sampling found high levels of contamination in residential areas as far as 1.7 miles away. But in 2022 a federal district judge determined that DTSC had failed to prove Exide’s pollution could have caused that contamination.

That outcome may embolden Ecobat to push back against potential legal and financial responsibility beyond the fenceline.

Air dispersion studies conducted by state scientists have indicated that historical emissions may have extended as far as 1.6 miles from the smelter. But the company maintains that “the evidence collected to date does not indicate that Ecobat’s facility has had an adverse effect on its neighbors.”

The lack of conclusive evidence about neighborhood level-contamination has motivated younger residents to start their own investigation.

Avocado Heights is a tight-knit community almost surrounded by City of Industry. But this unincorporated piece of the San Gabriel Valley is kind of an emotional opposite to Quemetco’s industrial-zoned hometown.

A grid along and across three blocks each way lines up neatly with ranch-style homes. Behind one peachy-pink house, Elena Brown-Vazquez and her brother Sam keep horses, goats, chickens and other animals.

With dusty equestrian trails, Avocado Heights is a working-class neighborhood whose rhythm is informed by charrería culture: most people here have ties to Mexico, to places like Zacatecas or Jalisco, horse-loving country.

That was the draw for the Brown-Vasquez siblings, who moved here in 2020 to deepen their connection with their Mexican culture. Informal food vendors like mariscos carts came by during the pandemic. The open space allowed people to play music and grill and be near each other outside, safely. They found a sense of community.

But not long after arriving, the siblings received notice of a public meeting about the lead smelter. Elena saw kids running around yards, riding horses, and playing in the dirt, and she worried for herself and her neighbors.

Ecobat and DTSC “talk about doing due diligence and doing your job, but they’re not really even doing a good job of engaging the community,” she said.

Nayellie Diaz, a longtime La Puente resident and Sam Brown-Vasquez’s partner, nodded. She, Elena and Sam are among those who call themselves Avocado Heights Vaquer@s, who act “in defense of land, air, & water.” One of the group’s goals is to raise awareness about the pollution coming from the smelter in order to stop it.

“The problem for us on some level is, there’s uncertainty,” Sam said. He’s concerned about how much lead remains in soil, and where it came from. “The reality is right now, we could tell definitively if the lead that’s in the community is coming from [Ecobat],” he added. “But they won’t do that.”

Last year, DTSC held a public workshop to explain its recent multimillion-dollar order against Ecobat, which included no funding to investigate soil contamination.

“We want more data,” Elena said.

At that meeting, Sam and Elena met Karen Valladares, a fourth-year Ph.D. student in environmental and occupational health at the University of California, Irvine, and Daniel Talamontes, a doctoral student in environmental studies at Claremont Graduate University.

Elena, a teacher, is working with the young researchers to gather soil samples from homes close to Ecobat. Talamontes describes the grant-funded work as “guerilla science.” A lab at the University of Southern California is testing the samples and the team members will interpret them.

“We are skilled enough, and knowledgeable, and we don’t trust [DTSC’s and Ecobat’s] methodology,” Talamontes said.

So far, Valladares and Talamontes said the overwhelming majority of soil samples have shown levels of lead above 80 parts per million, which echoes the earlier company-funded testing. She said a sizable chunk of the new samples are between 200 and 400 parts per million. The presence of arsenic in the soil, along with lead, suggests a source other than motor vehicles or paint, she said. It points to the smelter.

“There are natural levels of arsenic in the soil, but they’re very low,” Valladares said. “To have anything higher than that, it’s not the leaded gasoline. It’s coming from somewhere.”

DTSC said it is “working on a sampling strategy to determine the nature of the elevated (greater than 80 mg/kg) lead contamination observed in the community, as there are multiple potential sources of anthropogenic lead.”

At a meeting last fall, DTSC’s then-deputy director Todd Sax acknowledged that state regulators have “independent authority” to order Ecobat to do additional work right now — but he emphasized that they needed “sufficient evidence” to do so.

“Because that’s potentially a legal situation…we have to make absolutely certain that the data that we have would stand up in court because it may come to that,” Sax said, responding to a question about why soil testing takes so long.

“So we are being extra careful and thorough with our analyses and with the development of plans to make sure that whatever we do, it’s going to be scientifically defensible, it’s going to be right and it’s going to stick.”

Sax no longer works at DTSC and has taken a job at the California Air Resources Board.

As the permit process for Ecobat’s smelter drags on, the company’s lawyers have been busy.

Ecobat has filed two lawsuits involving California’s newly constituted Board of Environmental Safety, conceived by the state legislature to improve accountability at the DTSC. The board can hear public appeals to permits, as it did last year when the Clean Air Coalition challenged a limited permit the DTSC gave Ecobat for equipment the company installed without prior approval. The board sided with the neighborhood group. Ecobat has filed a civil complaint in Los Angeles County Superior Court against the board and the DTSC to appeal that decision. It’s also suing for public records related to that case in Sacramento County Superior Court.

A more aggressive tone — and strategy — is evident in these recent filings. In one, Ecobat’s lawyers called the neighborhood activists’ conduct at the appeal meeting in November “extreme by any measure,” saying the Clean Air Coalition, or CAC, “made a circus of the meeting.” Ecobat spokesman Kramer pointed to one moment, more than five hours into the six-hour meeting, where board members admonished someone for making obscene gestures not visible on a YouTube recording of the event. “It led the board into error,” the lawyers wrote.

The coalition, Ecobat’s lawyer wrote, “has blindly opposed Ecobat’s efforts to obtain regulatory approvals as part of a broader ‘delay strategy.’” Neighbors of the facility counter that the delay is the company’s fault. Since the company first submitted its permit renewal application in 2015, regulators have sent it back for corrections three times. Only recently did the DTSC deem the application complete.

Ecobat also has sent a letter to Earthjustice’s Johnson Meszaros, to “notify” her that it considered the coalition’s public testimony and Instagram comments about the company to be false and potentially defamatory.

“Ecobat has been exceptionally patient but CAC’s conduct is extreme by any measure,” the letter said. In Ecobat’s written response to Public Health Watch, Kramer said unfounded statements “can generate unfounded alarm in communities.”

Johnson Meszaros considers the letter a kind of harassment, meant to limit public participation in decisions about the smelter.

“This is something you see — oil companies have been using defamation against folks for a while now,” she said. “I think what they are telling us is they are prepared to sue community volunteers to break their will.”

DTSC and the Board of Environmental Safety did not comment on the litigation.

“Permit renewals are not a right,” Johnson Meszaros said. “They’re earned from your past behavior choices.”

Only China has more cars on the road than the U.S. As long as Americans drive gas-fueled cars, lead acid batteries aren’t going anywhere, according to environmental historian Jay Turner.

“We’ve created a world that we co-inhabit with this lead and we can’t walk away from that,” said Turner, whose book “Charged” explores the value of batteries in a clean energy transition. Now that we’ve brought lead into the manmade environment, Turner said, there’s an obligation to handle it safely.

Doing that is more expensive in the U.S., where pollution controls are relatively tight, according to Perry Gottesfeld, an expert at the nonprofit OK International.

Just over a decade ago, a multinational conglomerate, Johnson Controls, built a new battery smelter in Florence, South Carolina. The $150 million facility was open for just under a decade and in that time it was fined by state regulators nine times. Johnson Controls spun off its battery division, which became a new company called Clarios. When the plant was shuttered in 2021, Clarios said in a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission that it was 25% cheaper to recycle batteries at its plants in Mexico.

Gottesfeld said the U.S. doesn’t do enough to stop such offshoring. “You’re supposed to handle your own hazardous waste unless you have the inability to do so,” he said.

All of that puts more pressure on California, which has acknowledged its own outsourcing of hazardous waste — and which has 35 million registered vehicles on its roads.

It also presses down on the communities around the Ecobat facility. Avocado Heights resident Elena Brown-Vasquez has heard the argument before: California needs to clean up after itself. Battery recycling plants just south of the border are known to make workers sick. “We all get that a lot, we do,” she said.

But residents say they’re pushing back because their own health is in jeopardy, too.

They worry that if DTSC renews Ecobat’s permit, the South Coast Air Quality Management District could allow the company to boost daily production by 25%. Ecobat has been seeking to expand for years, but local advocates have been pushing back longer.

An early skeptic was Lilian Avery, who moved to Hedgepath Avenue in Hacienda Heights in 1956. Back then, she said during a 1996 DTSC public meeting, her neighbor was “an Armstrong rose garden; acres and acres of roses.” And then the smelter came in.

“I have had concern about Quemetco all these years,” Avery is quoted as saying in a transcript of the meeting. “They are trying hard to be good neighbors, but they have chosen the wrong plot.”

Public Health Watch is a nonprofit investigative news organization that covers weaknesses and injustices in the nation’s health systems and policies, exposes inequities and highlights solutions.

This story has been updated to reflect a late response from California’s Department of Toxic Substances Control.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline California communities are fighting the last battery recycling plant in the West — and its toxic legacy on Apr 22, 2024.

Lead poisoning is often treated as if it’s a problem of the past. But its harmful legacy lingers today, particularly in the soil of urban centers across the United States.

One in every two American children under the age of 6 tested between late 2018 and early 2020 had detectable levels of lead in their blood. Studies show soil exposure is a major reason.

The lead pumped out of exhaust pipes and industrial smokestacks decades ago can still be found in soil. Lead paint used extensively throughout the first half of the 20th century remains on the interior and exterior walls of many homes, degrading to chips and dust that also end up in soil. And although the U.S. began phasing out lead in automobile gasoline and consumer paint in the 1970s, new lead pollution continues to be dumped on communities every year from industrial sites and the aviation gas used by small aircraft.

Yet while the threat of lead exposure via paint and water is well documented, soils aren’t systematically tested and mapped to prevent exposure to this invisible neurotoxin.

The Center for Public Integrity and Grist have created a toolkit to help fill these information gaps and arm journalists and community members with the skills needed to do their own testing and analysis. The detailed guide walks readers through how to test the soil, map their results and investigate potential sources, both present and past.

As part of this effort, Public Integrity and Grist will host several training workshops on the major tools and takeaways from the new guide. For journalists interested in coverage ideas and information about testing, join us either April 23 or April 25, both at 1 p.m. Eastern (10 a.m. Pacific).

For those interested in learning more about how to tackle soil lead contamination in their communities, join us April 30 at 1 p.m. Eastern (10 a.m. Pacific). Register here. You’ll also get an invitation to an additional brainstorming session to further tailor these approaches to your area.

Experts say that identifying the environmental sources of contamination is key to preventing lead poisoning in children. Once a child has been exposed, the damage cannot be reversed, which makes environmental testing and mapping imperative.

Decades of research have shown the lasting harm for children exposed to lead, from brain development impacts — the capacity to learn, focus, and control impulses — to later health risks like coronary heart disease. No amount, scientists say, is safe.

Our toolkit offers suggestions no matter what stage you’re at in your journey to learn about soil lead contamination. If you’d like to know what existing data indicates, for example, this map referenced in the toolkit shows how common elevated lead levels are in children by census tract or ZIP code in 34 states. Public health agencies fail to adequately test children’s blood for lead exposure, research shows, but existing data can point to potential trouble areas for soil, paint, or water exposure.

If you’d like to know whether the soil in your city might be contaminated but don’t have the resources to conduct widespread testing, you can start small by testing in your backyard or a handful of properties in your neighborhood. The toolkit includes information about the online portal Map My Environment, an initiative that allows you to send in test samples to be analyzed for free. You’ll also see recommendations on lead interventions.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How to investigate toxic lead lurking in your community’s soil on Apr 22, 2024.

This story was originally published by Capital B.

After a year-long legal battle with a railroad company over their land, landowners in a rural, majority-Black town in Georgia may be forced to sell their homes.

In an initial decision on April 1, a Georgia Public Service Commission officer approved a proposed rail spur in Sparta. Several property owners had refused to sell the land to Sandersville Railroad Co. In March, the centuries-old, white-owned private railroad company sought to acquire the property through eminent domain — a process that allows the government to take private land for public use. However, property owners must receive fair compensation.

The company petitioned the state’s public service commission to condemn the land parcels from 18 property owners along Shoals Road. The railroad company planned to construct a 4.5-mile rail spur that would connect the Hanson Quarry, a rock mine owned by Heidelberg Materials, to a main train line along a nearby highway. The proposed project would create 20 temporary construction jobs, a dozen permanent jobs averaging $90,000 a year in salary and benefits, and bring in over $1.5 million annually to Hancock County.

However, residents in the town of 2,000 told Capital B in September that they didn’t want to sell their land, or that they fear the potential damage to their homes from the train. Many others say they never received a notice from the railroad company and only found out about the project at a local community meeting last year.

The Georgia Public Service Commission held a three-day hearing in late November. The Institute for Justice, a nonprofit, public interest law firm, and residents argued the railroad project is an abuse of eminent domain that doesn’t serve the public or benefit the community.

Benjamin Tarbutton III, Sandersville Railroad’s president, testified that economic development is important to him and “the American dream starts with a job.” He believes his railroad project will provide jobs, which is why he deems the project public use.

Bill Maurer, an attorney with Institute for Justice who represents Sparta property owners, later asked Tarbutton: “Do you think part of the American dream is having property without it being taken for others’ use?”

“I’m going to stick with my first comment,” Tarbutton said.

During Sparta native Marvin Smith’s testimony, he also mentioned the American dream. Smith, a military veteran, owns property that was passed down to him from his father. His grandfather, James Blaine Smith, acquired 600 acres in 1926.

“The American dream says if you play by the rules and work hard, justice will prevail, and you will be rewarded,” he said. “It never occurred to me … over 43 years of playing by the rules … I would end up in a position where my land could be taken through eminent domain.”

Despite the residents’ plea, Thomas K. Bond, hearing officer for the public service commission, ruled in favor of the railroad company.

“I therefore find and conclude that the proposed condemnation by the Sandersville Railroad serves a legitimate public purpose and is necessary for proper accommodation of the business of the company,” Bond wrote. “The petition of Sandersville Railroad, as amended, is granted.”

The fight isn’t over, and the initial decision isn’t the final say in the case. Property owners, who are represented by the Institute for Justice, will challenge the ruling. They have 30 days to appeal.

There have been efforts to make it harder for companies to use eminent domain after the widely cited Kelo v. City of New London case. In 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the government taking private property to facilitate a private development for economic benefits is considered to be a public use. Since then, at least 44 states have passed laws to alleviate the abuse.

“When the U.S. Supreme Court issued the unpopular and widely condemned Kelo decision, the Georgia General Assembly passed strict reforms to ensure that nothing like that would happen in this state. Today’s initial decision essentially undoes that work,” Maurer said in a statement. “We will fight to ensure that the people of the state of Georgia are protected from this kind of abuse at every stage we can.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Rural Georgia community battles railroad trying to take their land on Apr 21, 2024.

This story was originally published by High Country News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

On April 12, the Department of Interior released a new rule that will impose stricter financial requirements for oil and gas companies that operate on federal public land — the first such change since 1960.

The reform includes a jump in the amount of money that drilling companies must put forward to ensure cleanup of their wells. It also raises the royalty tax rate that operators pay on the minerals they extract on public land, which had not changed in more than a century.

In a statement, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland said that the changes will “cut wasteful speculation, increase returns for the public, and protect taxpayers from being saddled with the costs of environmental cleanups.”

The final version of the rule, which was released in draft form last summer, joins a flurry of climate and conservation moves by the Biden administration in recent weeks, including a strengthened methane emissions standards for oil wells on federal land and a renewable energy policy meant to promote wind and solar development. Environmental groups praised the rule as long overdue.

“These new regulations are the kind of common-sense reforms the federal oil and gas leasing program has needed for decades,” said Athan Manuel, Sierra Club Lands Protection Program director, in a statement.

The increase to bonding requirements means that the government will have substantially more money set aside to pay for cleaning up abandoned oil and gas wells. In order to drill, energy companies put forward funds, most often in the form of bonds purchased with a third-party surety company, to ensure that cleanup takes place.

These bonds are held until the company plugs its wells. If the company performs the reclamation work itself, it gets its bonds back. If a company goes bankrupt or abandons its wells some other way, the government can use the money in the bonds to pay for plugging and environmental cleanup.

Bonding levels need to be high enough to incentivize cleanup over abandonment, and Interior Department’s bonds hadn’t changed in more than six decades. A 2019 report from the Government Accountability Office found that between 84 percent and 99 percent of bonds for public land wells do not cover the full cost of cleanup. The new rule raises the minimum bond for a single public land oil and gas lease — which often contains multiple wells — from $10,000 to $150,000. For companies that operate multiple leases in the same state, the bond increases from $25,000 to $500,000.

Despite these increases, the new bonding levels are unlikely to cover the complete cost of cleaning up the more than 90,000 unplugged wells overseen by the Bureau of Land Management. The same 2019 GAO report found a wide range of plugging costs for orphaned wells on public land, ranging from $20,000 to as much as $145,000 per well, with a median cost of $71,000 to plug the well and clean up the drilling site.

Insufficient bonding often leads to wells being left idled — not producing, but also unplugged. Studies show that idled wells are more likely to become orphaned, with the financial burden for cleanup falling on public regulators — and ultimately on taxpayers. The Interior Department estimates that there are 3.5 million abandoned oil and gas wells in the U.S., which are substantial sources of methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

The new rule mandates that active operators on public land come into compliance with the new financial standards over the next three years and requires an update every 10 years to keep up with inflation.

The new rule also increases the royalty tax rate that companies pay on profits from minerals extracted on public land, which will mean a windfall for Western states like Alaska, California, Colorado, New Mexico, and Wyoming. The previous royalty rate of 12.5 percent was set in 1920. The new rate of 16.67 percent was mandated by the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022, which also raised the minimum bid for an oil and gas lease to $10/acre, up from $2/acre.

About half of this new revenue will go to the states where the drilling takes place, to fund public services. In oil and gas-producing states, it’s already a major source of income. In some years, New Mexico has taken in more than a billion dollars annually from BLM oil and gas operations, thanks to leasing sales in the Permian Basin. Still, Taxpayers for Common Sense, a non-partisan fiscal think tank, estimates that the government lost more than $12 billion in revenue between 2010-2019 because royalty rates were too low.

The oil and gas industry was not pleased with the final version of the rule. In a statement, Kathleen Sgamma, president of the Western Energy Alliance, an oil and gas trade group, said the changes will drive small operators off public land and suggested that the group may sue.

“This is another rule by the Biden administration meant to deliver on the president’s promise of no federal oil and natural gas,” she said in a statement, referencing a pledge by President Biden during the 2020 presidential campaign to ban drilling on public land. “Western Energy Alliance has no other choice but to litigate this rule.”

While most environmental advocates praised the rule, some criticized the administration for failing to live up to this same campaign promise – arguing that better financial return from oil and gas drilling is not the same as banning the practice.

“Reading this rule is like finding an old floppy disk,” said Gladys Delgadillo, a climate campaigner at the Center for Biological Diversity, in a statement. “It doesn’t belong in 2024. Updating oil and gas rules for federal lands without setting a timeline for phaseout is climate denial, pure and simple.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Drilling for oil on public land in the US is about to get more expensive on Apr 20, 2024.

If you’ve ever listened to “Riders on the Storm” by The Doors, you know that before any music from instruments begins, there is the sound of heavy rain and thunder, giving the song an ambience created by the “music” of nature. Likewise, about halfway through “Blackbird” by The Beatles, the sound of a male blackbird singing adds the inimitable chorus of the natural world to the melody.

As much as nature’s music has been sampled and added to songs over the history of modern music, its symphony of sounds have never been credited or given royalties.

Sounds Right is a new Museum for the United Nations – UN Live initiative that will allow artists who use sounds from the natural environment in their recordings to credit “NATURE” as a featured artist on streaming platforms like Spotify and give a portion of the royalties to conservation, a press release from the UN said.

“Sounds Right is a groundbreaking music movement. It unites people around the world in a shared commitment, recognizing the intrinsic value of nature. Together, we must act now to protect our planet for our common future,” said Melissa Fleming, UN under-secretary-general for global communications, in the press release.

With the goal of starting a global conversation about nature’s value, the platform will give millions of music listeners the chance to take action to help our planet.

An international mix of artists have already joined Sounds Right and released or mixed tracks that include Earth sounds to Spotify’s “Feat. NATURE” playlist, including Brian Eno, Ellie Goulding, AURORA, MØ, Anuv Jain and Bomba Estéreo.

“From Colombia to India by way of Norway, Venezuela, Kenya, Denmark, UK, U.S. and Indonesia, there is a truly global selection of artists taking part and highlighting natural sounds from a vast range of ecosystems all over the world,” the press release said. “Brian Eno brings a visceral aspect to his David Bowie collaboration ‘Get Real’ with the harsh cries of hyenas, rooks and wild pigs.”

It has been projected that the Sounds Right project will engage more than 600 million individual listeners and generate over $40 million in the first four years.

“The initiative comes at a critical time. Wildlife populations have declined by an average 69% in the past 50 years and at least 1.2 million plant and animal species are estimated to be at threat of extinction. Sounds Right looks to flip our extractive relationship with the natural world on its head while recognising nature’s contribution to the creative industries,” the press release said.

Donations and royalties for Sounds Right will be collected by Brian Eno’s nonprofit EarthPercent in the United States and United Kingdom and directed toward restoration and biodiversity conservation projects in threatened ecosystems globally. An independent Expert Advisory Panel of mostly Global South conservationists — including Indigenous representatives, environmental activists, biologists and conservation funding experts — will guide distribution of the funds.

“Popular culture, like music, has the power to engage millions and millions of people, ignite positive global change at scale, and get us all on a more sustainable path. In a world where empathy is declining and many people often feel that their actions hardly matter, Sounds Right and UN Live meet people where they already are — on their screens and in their earbuds — with stories and formats they can relate to, and actions that matter to them,” Katja Iversen, Museum for the United Nations – UN Live CEO, said in the press release.

The Sounds Right project is a collaboration between the Museum for the United Nations – UN Live and partners including EarthPercent, Music Declares Emergency, Earthrise, The Listening Planet, Biophonica, Community Arts Network and Limbo Music.

Current EarthPercent targets include conservation efforts in Indian Ocean islands and Madagascar and the prevention of deep-sea mining.

“Hopefully it’ll be a river, or a torrent, or a flood of royalties — and then what we do is distribute that among groups of people who are working on projects to help us deal with the future,” Eno said, as BBC News reported.

“If you’re listening to a beautiful piece of music, you’re hearing the possibility of a good world that we could be in,” Eno added. “I feel that we’re in the middle of an enormous revolution. It shows in the very small things that people do. Their distaste for waste, for example. The feeling that irresponsible consumerism is actually not very pleasant… The people who run the fossil fuel companies, the people who pay advertising companies to tell lies about what is really happening [in the environment] are on their way out. I don’t think they have a platform in the future.”

The post Sounds Right Recognizes Nature as Musician, With Royalties Going to Environmental Causes appeared first on EcoWatch.

On Friday, the Environmental Protection Agency designated two types of “forever chemicals” as hazardous substances under the federal Superfund law. The move will make it easier for the government to force the manufacturers of these chemicals, called per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances or pfas, to shoulder the costs of cleaning them out of the environment.

The EPA “will focus enforcement on parties who significantly contributed to the release of PFAS chemicals into the environment, including parties that have manufactured PFAS or used PFAS in the manufacturing process, federal facilities, and other industrial parties,” the agency explained in a press release. The designation, which will take effect in 60 days, comes on the heels of an EPA rule limiting the acceptable amount of the two main types of PFAS found in the United States, PFOS and PFOA, to just 4 parts per trillion.

Although the EPA’s new restrictions are groundbreaking, they only apply to a portion of the nation’s extensive PFAS contamination problem. That’s because drinking water isn’t the only way Americans are exposed to PFAS, and not all companies spreading PFAS into the environment deliberately added the chemicals to the products. In Texas, a group of farmers whose properties were contaminated with PFAS from fertilizer are claiming the manufacturer should have done more to warn buyers about the dangers of its products. The first-of-its-kind lawsuit illustrates how much more regulation will be needed to rid the environment — and Americans’ bodies — of forever chemicals.

PFAS have been around since the middle of the 20th century, when chemical giants DuPont and 3M started putting them in products such as nonstick cookware, firefighting foam, and tape. The chemicals, ultra-effective at repelling water, quickly became ubiquitous in products used by Americans every day: pizza boxes, takeout containers, popcorn bags, waterproof mascara, rain jackets.

But the stable molecular bonds that make the chemicals so effective in these applications also make them dangerous and long-lasting. The chemicals bind to blood and tissue, where they can build up over time and contribute to a range of health issues. The chemicals have been linked to testicular, kidney, and thyroid cancers; cardiovascular disease; and immune deficiencies. Over decades, as chemical companies led by 3M obscured the dangers of PFAS from federal regulators and the public, the chemicals leached into the environment and migrated into soil and drinking water supplies. They seeped into us, too; 97 percent of Americans have PFAS in their blood.

PFAS are also in our excrement — which is a problem because of where that waste ends up. Biosolids, the concentrated byproducts of waste treatment plants, are commonly spread on farms as a fertilizer. The products are incredibly cheap — a selling point for farmers who are often working with razor-thin profit margins. Some 19 billion pounds of wastewater sludge was spread on farmland in 41 states between 2016 and 2022. The EPA estimates that 60 percent of biosolids in the U.S. are applied to agricultural lands.

There’s growing evidence that biosolids are rife with forever chemicals that have traveled through people’s bodies. The EPA’s new PFAS rules don’t apply to biosolids, which means this contamination is largely still flying under the radar. The EPA said it aims to conduct a first-ever assessment of PFAS in biosolids later this year, which may result in new restrictions. Preliminary research has shown that the PFAS in waste sludge is absorbed by crops and, in turn, consumed by livestock; it’s even been found in chicken eggs. Some farmers aren’t waiting for the federal government to take action.

In February, five farmers in Johnson County, Texas, sued Synagro, a biosolids management company based in Maryland, and its subsidiary in Texas. Synagro has contracts with more than 1,000 municipal wastewater plants in North America and handles millions of tons of waste every year. The company separates liquids and solids, and then treats the solids to remove some toxins and pathogens. But PFAS, thanks to their strong molecular bonds, can withstand conventional wastewater treatment. Synagro repurposes 80 percent of the waste it treats, some of which is marketed as Synagro Granulite Fertilizer.

The lawsuit claims Synagro “falsely markets” its fertilizers as “safe and organic.” The plaintiffs accuse the company of selling fertilizer with high levels of PFAS and failing to warn farmers about the dangers of PFAS exposure. They say an individual on a neighboring property used Synagro Granulite, and the product then made its way onto their farms.

Dana Ames, Johnson County’s environmental crimes investigator, opened an investigation after the plaintiffs made a complaint to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality and the Johnson County constable’s office. Ames tested soil, surface water, and well water samples from the affected farms for PFAS. She found contamination ranging from 91 to 6,290 parts per trillion in soil and water samples from the plaintiffs’ properties. The county also tested tissue from two fish and two calves on those farms. The fish tested as high as 75,000 parts per trillion. The liver of one of the calves came back with an astounding 610,000 parts per trillion of PFOS — about 152,000 times higher than the EPA’s new PFAS drinking water limits.

The plaintiffs voluntarily stopped selling meat, fish, and other agricultural products after discovering the contamination. They’re suing Synagro to recoup their losses and more damages they say are sure to come. Synagro, the complaint reads, failed to conduct adequate environmental studies and the company “knew, or reasonably should have known, of the foreseeable risks and defects of its biosolids fertilizer.”

A spokesperson for Synagro told Grist the company denies the “unproven and novel” allegations. “EPA continues to support land application of biosolids as a valuable practice that recycles nutrients to farmland and has not suggested that any changes in biosolids management is required,” the spokesperson said, highlighting the lack of federal regulations.

Ames, the investigator, said that federal and state inaction is the real root of the problem. “EPA has failed the American people and our regulatory agency here in the state of Texas has failed Texans by knowingly allowing this to continue and knowingly allowing farms to be contaminated and people, too,” Ames told Grist.

In response to Grist’s request for comment, the EPA confirmed that recent federal PFAS restrictions do not affect the application of biosolids on farmland. The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality declined to comment on the ongoing litigation in Texas.

Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, an environmental nonprofit that helped organize the PFAS testing on the plaintiffs’ properties in Texas, is considering filing its own lawsuit against the EPA for not implementing restrictions on PFAS in biosolids. “They have a mandatory duty to look at what pollutants are in these biosolids and set standards for them,” said the group’s science policy director, Kyla Bennett, who is a former EPA employee. “They have not followed through.”

The Texas plaintiffs aren’t the only farmers struggling with a PFAS contamination problem due to the use of biosolids. Maine already banned the use of biosolids as fertilizer in 2022 after dozens of farms tested positive for forever chemicals. A farmer in Michigan who used biosolids fertilizer was forced to shut down his 300-acre farm after state officials found PFAS on his property. It’s likely that any farmland in the U.S. that has seen the use of biosolids products has a PFAS problem. “No one is immune to this,” Bennett said. “If people don’t know that their farms are contaminated it’s because they haven’t looked.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline The EPA is cracking down on PFAS — but not in fertilizer on Apr 19, 2024.