In August 1817, the learned men of the Linnaean Society of New England had studied…

The post Adaptive Management: The Sea Serpent, Organized Growth and Natural Harmony appeared first on Earth911.

In August 1817, the learned men of the Linnaean Society of New England had studied…

The post Adaptive Management: The Sea Serpent, Organized Growth and Natural Harmony appeared first on Earth911.

James Parravani came down with flu-like symptoms the day before his daughter’s wedding reception. He had a fever, a headache, and chills. It was Labor Day weekend 2021, and his family thought he might have COVID-19. But a test at an emergency room near his home in Westchester, New York, came back negative.

The ER doctors quickly transferred Parravani to Yale New Haven Hospital in Connecticut, where he had received a kidney transplant a year prior. The specialists there suspected he might have a kidney or blood infection related to his operation. They gave him a round of antibiotics, but he just kept getting worse.

Parravani, known to friends and family as Jim, took a long, winding road to his daughter’s wedding weekend. He dropped out of high school in Schenectady, New York, before his senior year to focus on other priorities. “Rocktoberfest” — a music festival he and his friends threw in a rented-out motel — occupies a near-mythical place in modern Schenectady history. Parravani eventually earned his GED and attended Syracuse University’s College of Law, where he rose to second in his class.

After marrying his middle school sweetheart in 1986, Parravani graduated from law school, moved to Westchester, and began building a career and a family. But in the ’90s, he learned he had a genetic condition called polycystic kidney disease — an illness that causes cysts to grow on the kidneys and often results in organ failure. After several years of treating his cysts, Parravani’s doctors initiated the laborious process of getting him a transplant. In 2020, about a year before his daughter’s wedding weekend, he finally got one.

Now, his doctors thought this transplanted kidney might be making him sick, though they still didn’t know how. The morning of her reception, Jenny Parravani Davis called her dad at the hospital. She asked him if he wanted her to postpone the festivities. “No, no,” he told her. “Keep going.”

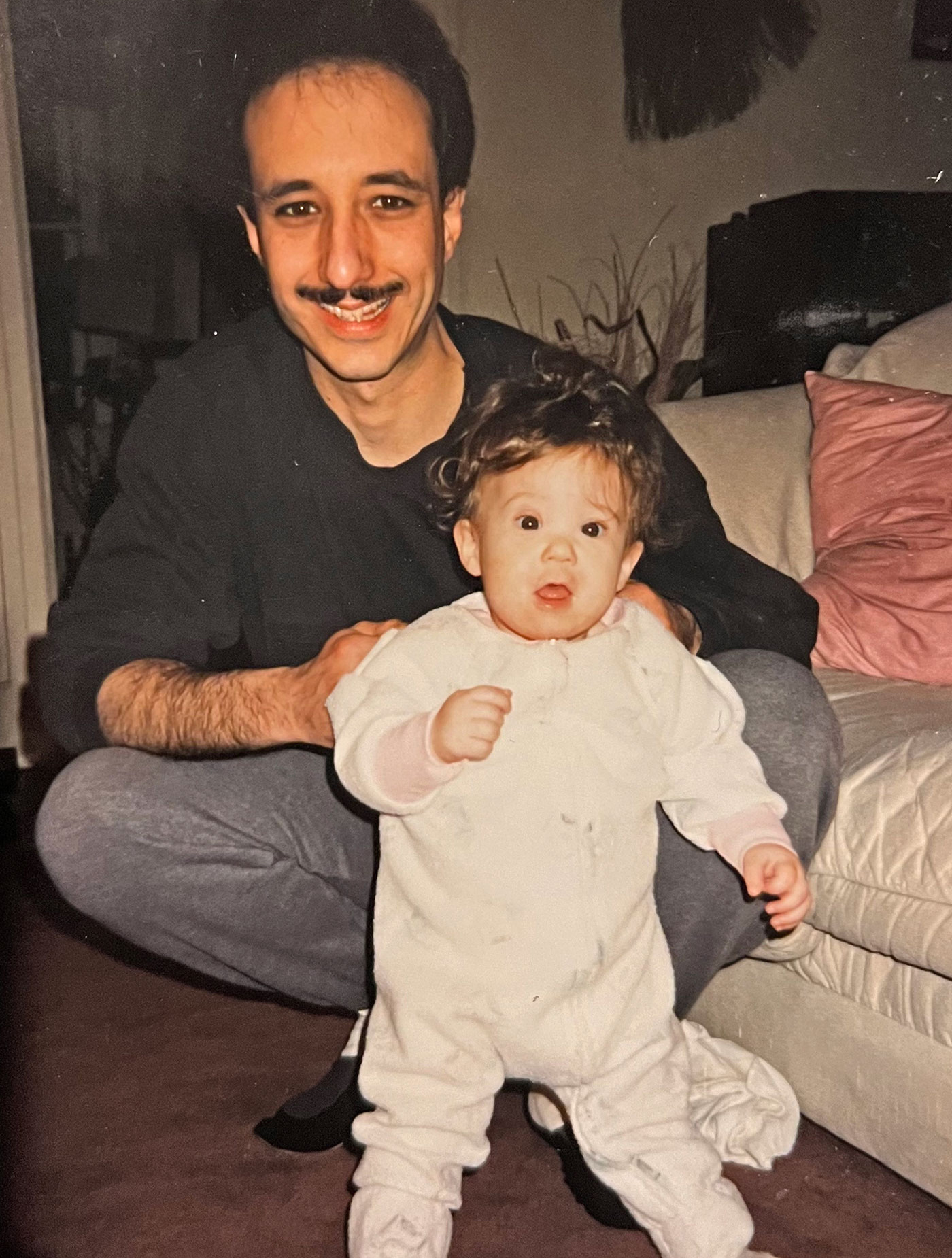

From left: Jim Parravani with his daughter, Jenny, as a toddler. Father and daughter on Jenny’s prom night. Courtesy of Jenny Parravani Davis

That was the last lucid conversation Davis ever had with her father. The next day, she got a call from her mother. Parravani was deteriorating — fast.

“He got on the phone and he was really disoriented, he couldn’t form words,” Davis said. “I remember saying ‘Hi, I love you,’ and he just said, ‘Don’t cry,’ and everything after that was incoherent.” Parravani was intubated that same day.

The doctors ran dozens of tests and put Parravani on multiple courses of strong antibiotics to treat the infection. It was only when they conducted a spinal tap — about a week after Parravani’s initial admission — that they discovered the true culprit: West Nile virus was present in his cerebrospinal fluid. The disease had spread to his brain and was making it swell. (Yale New Haven Hospital declined to comment on Parravani’s care.)

For seven months, as Parravani slipped in and out of comas, the doctors tried to beat back the virus with intravenous fluids, pain medication, and oxygen. At one point, it looked like Parravani might pull through. He was nodding and trying to communicate with his family around his breathing tube. The doctors reduced the oxygen flowing through his ventilator, and he breathed on his own. But in March 2022, Parravani began to decline again. On April 13, Parravani died in hospice care. He was 59 years old.

West Nile has been the most common mosquito-borne illness in North America for more than two decades. States in the Great Plains and western U.S. typically report the highest number of cases, though outbreaks have happened in nearly every state in the continental U.S. The disease has killed more than 2,300 people since it first arrived here, and the number of people affected by the virus every year is poised to rise.

As climate change extends warm seasons and spurs heavier rainstorms, the scope and prevalence of West Nile virus is shifting, too. Warmer, wetter conditions allow mosquitoes to develop more quickly, stay active beyond the traditional confines of summer, and breed more times in a given year. Birds, which host West Nile virus and pass it onto mosquitoes that bite them, are adjusting their migration patterns in response to the melding seasons.

The confluence of these two trends could have serious consequences for human beings. West Nile virus, a recent study said, “underlines once again that the health of animals, humans, and the environment is deeply intertwined.” In the past few years, Colorado and Arizona recorded outbreaks of the virus that killed scores of people in each state. Parts of California and Wyoming also reported unusually high cases of the disease. Meanwhile, Nevada, Illinois, and New York registered above-average or record-breaking numbers of West Nile-infected mosquitoes and mosquito activity.

“Overall, the evidence points to higher temperatures resulting in more bird-mosquito transmission and more what we call spillover infections to people,” said Scott Weaver, chair of the department of microbiology and immunology at the University of Texas Medical Branch.

West Nile virus typically leaves young, healthy individuals unscathed. Only 1 in 5 people who contract it develop symptoms, which can include fever, headache, joint pain, diarrhea, and other signs of illness that often resemble the flu.

There is no cure for West Nile virus; the immune system must fight it off on its own. That’s why elderly people and those with preexisting conditions, such as cancer, diabetes, and kidney disease, are at much higher risk of developing the severe form of the disease. So are organ transplant recipients, who take immunosuppressants for their entire lives to ensure the body does not reject the organ.

About 1 in 150 people who get West Nile develop the worst form of the illness, in which the virus attacks the central nervous system. For 10 percent of these patients — including Parravani — encephalitis or meningitis, swelling of the tissues around the brain and spinal cord respectively, leads to death.

Because only a sliver of infected people get seriously sick, the impact of West Nile virus on the public hinges on the number of people who contract the disease. Some years, the number of infections detected in the U.S. approaches 10,000. Other years, there are fewer than 1,000 reported cases. The number depends in large part on environmental conditions — how much rain fell, how warm or cold the spring or fall was — in addition to bird migration patterns and human behavior.

“It’s a rare event that any given mosquito bites a bird and then survives long enough to bite a human” and transmit West Nile virus, said Shannon LaDeau, a disease ecologist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies. But as with COVID-19, the size of the denominator is crucial. “When you have millions of mosquitoes, that rare event happens more frequently.” LaDeau said.

Parravani’s illness wasn’t the first case of West Nile to stump medical professionals in the U.S. In August 1999, people in the New York City metropolitan area started becoming severely ill with encephalitis. The patients had previously been healthy and reported being outside in the days leading up to their illness. The New York City Department of Public Health suspected a disease spread by mosquitoes was behind the outbreak and immediately launched an investigation.

In the months before the outbreak, researchers in New York had detected an unfamiliar type of single-stranded RNA virus in some of North America’s wild birds. Birds of prey and members of the crow family, in particular, were dying in unusually high numbers. Four weeks after the people in New York got sick, the chief pathologist at the Bronx Zoo connected the dots and sounded the alarm. The birds were infected with West Nile virus, named after the district in northern Uganda where the disease was first isolated in a human more than half a century earlier. And West Nile, public health authorities eventually confirmed, was what was making New Yorkers sick.

By the end of the summer, 59 people had been hospitalized with West Nile virus. Seven died.

West Nile had been known for decades to cause fever, vomiting, headache, and rashes. Epidemics in the Middle East in the early 1950s helped researchers confirm that the Culex genus of mosquito — dawn and dusk biters that prefer to feed on birds — were the primary vector, or carrier, of the disease. Outbreaks of varying severity cropped up all over the world — in France, India, Israel, Italy, Morocco, Romania, Russia, South Africa, Spain, and Tunisia. But it wasn’t until 1999 that researchers understood that migratory birds could spread the virus from one hemisphere to another.

Once public health officials learned what was behind the encephalitis outbreak in New York, they sprayed pesticide and larvicide around the city to kill mosquitoes. But the disease couldn’t be eradicated. Within three years, birds had carried it from coast to coast and throughout much of Canada.

The public health response to West Nile virus in the U.S. since the turn of the century has been punctuated by successes and setbacks. Every few years, when environmental conditions allow Culex populations to boom, cases careen out of control and hundreds of people die. States and cities often belatedly deploy weapons from a limited arsenal — pesticide-spraying and public awareness campaigns — to keep the disease in check. After a boom year, the next one often brings a different cocktail of environmental conditions, and the disease has a much smaller impact on public health.

“There are many things that go into what causes the circulation of West Nile,” said J. Erin Staples, a medical epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC. “And that makes it very difficult for us to predict.”

The unpredictability of the virus is part of what explains the lackluster response by states and the federal government to the threat of West Nile. No vaccine or cure exists, and funding for research on the disease is low, despite the fact that the virus has been claiming lives in North America for a quarter of a century. “Although West Nile virus continues to cause significant morbidity and mortality at great cost, funding and research have declined in recent years,” a 2021 study said. The National Institutes of Health directed $67 million to West Nile research between 2000 and 2019 — less than a tenth of the $900 million it dedicated to research on Zika, a mosquito-borne illness that never gained a foothold in the U.S., in the same period.

Experts warn that climate change is creating more opportunities for West Nile to spread.

Culex mosquitoes thrive in temperate, wet weather. Like other mosquitoes, they lay their eggs in standing pools of water. The eggs can’t survive below about 45 degrees Fahrenheit, but as temperatures get warmer from there, the time between hatching and reproducing gets shorter. The mosquitoes’ ideal temperature for survival ranges from 68 to 82 degrees Fahrenheit, depending on the precise species, but one Culex species can spread West Nile when it’s anywhere between 57 and 94 degrees F outside.

As temperatures rise and make fall, winter, and spring milder, Culex mosquitoes will have more chances to reproduce and spread West Nile in places that didn’t used to see so many mosquitoes. Meanwhile, because a warmer atmosphere holds more water, extreme rain events are getting more common — and that means more standing water for mosquitoes to breed in.

In New York, where winters are warming three times faster than summers, mosquitoes are now active deep into the month of November. A few decades ago, an adult mosquito flying around past the middle of October would have been highly unusual. “We are starting to see and will continue to see shifts in the range” of West Nile virus, said Laura Harrington, an entomology professor at Cornell University, “and shifts in some of the avian hosts that are most important.”

Climate change also pushes birds into new areas, because of weather changes and adjustments in where and when different types of plants and trees grow and bloom. “There are changes to the habitat where birds migrate to breed every year in the Northern Hemisphere,” said Weaver, the University of Texas microbiologist. “And just the temperature itself may have an impact on migration.” As birds enter new habitats, they have the potential to bring West Nile with them.

There’s already evidence that climate change is fueling West Nile outbreaks. In 2021, Maricopa County, Arizona, got an unusual amount of rain — 6.6 inches between June and September, compared to the 2.2 inches it usually gets during that period. That summer, Maricopa County experienced a historic surge of West Nile virus — the worst outbreak in a U.S. county since the disease arrived 25 years ago. Roughly 1,500 people were diagnosed, 1,014 were hospitalized, and 101 people died. The previous year, the number of recorded cases in the region was in the single digits.

A determining factor in the outbreak, Staples said, was the unusual amount of rain. It led to “an unprecedented increase in the mosquitoes and the ability of that virus to then spread to people.” Arizona is projected to get more bouts of extreme rainfall as the planet warms.

To prevent West Nile outbreaks, public health officials must monitor mosquitoes and birds for the virus. But the behavior of mosquitoes makes surveillance complicated — trickier even than tracking other vectors of disease, such as ticks. Unlike ticks, which stay more or less put, mosquitoes can travel a mile or two in any direction. That means public health agencies must launch an expensive and time-consuming hunt for the bugs, using field tests, maps, and guesswork to figure out where mosquitoes are hiding. Birds are mobile, too, and that further complicates efforts to track, map, and control the disease.

Even accounting for these challenges, epidemiologists say too few states are deploying sufficient effort and resources to make sure that they are able to predict and respond to outbreaks of West Nile virus. “We still are using the same vector control and the messaging to use your insect repellant that we were using 25 years ago,” Staples said.

Some states are doing a better job than others. Massachusetts and New York, among the most aggressive states in the nation when it comes to tracking West Nile virus, test mosquito breeding sites and birds regularly and, when positives come back, use that information to inform the public. After Parravani’s spinal tap revealed that he had West Nile, the Westchester County Health Department went to his house and conducted a sweep of the property. County public health officials drained pools of standing water in the backyard where the mosquitoes had likely bred, and they encouraged nearby residents to do the same on their own properties.

“In some places there’s a very clear link that guides when you test and what you test for,” LaDeau said. But “mosquito surveillance is not the norm across all regions, and it’s not standardized among even regions within a state.”

As climate change loads the dice in favor of mosquitoes, West Nile is not the only infectious illness in flux. The number of cases of vector-borne disease in the U.S. have more than doubled since 2001. Some of that increase can be attributed to better disease awareness among physicians and the public, and an uptick in testing as a result. But there are also examples of diseases bursting out of the regions where they have historically been found, which may be an indication that changes in the environment are coaxing carriers of disease into new places.

In 2023, the U.S. saw the first-ever cases of locally transmitted dengue fever in Southern California and unusual cases of locally acquired malaria in Texas, Florida, and Maryland. When a mosquito imparts West Nile virus to a human, the transmission of the virus stops there. An infectious human cannot infect a mosquito with the virus. That’s not the case for dengue and malaria, which makes the spread of those diseases potentially far more dangerous.

Many studies show that infectious diseases will take a larger toll on public health across North America as we make our way deeper into the 21st century. “More Americans are at risk than ever before,” Christopher Braden, the acting director of the CDC’s Center for Emerging and Infectious Zoonotic Diseases, warned in 2022.

If West Nile virus, the nation’s most common mosquito-borne illness, is a test for how the U.S. will weather the coming influx of vector-borne disease, then the country is in bad shape. “We don’t have very good tools to control it and prevent human illness,” Harrington said.

For now, however, those who have been personally impacted by mosquito-borne illnesses are arming themselves with DEET and ringing the alarm. Until recently, Jenny Parravani Davis worked as a communications manager for the Wilderness Society, a land conservation organization that advocates for better protection of the nation’s remaining wild places. The climate change reports that the Wilderness Society puts out generally include top-line findings about the ways in which climate change will erode human health as temperatures rise. But her father’s death, Davis said, drove home just how interconnected these issues really are.

“I started to connect the dots and see the bigger picture,” she said. Her backyard in Virginia collects a lot of water, especially in recent years, as back-to-back record-setting rain events have flooded the state. “I don’t think anyone would blame me, but I’ve developed this neurosis where anytime I scratch a mosquito bite I’m like, ‘Could this be the thing that kills me today?’” she said. “I’ve seen what happens when we don’t pay attention to these things.”

Correction: This story originally misstated Jenny Parravani Davis’ first name.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline When West Nile virus turns deadly on Jun 20, 2024.

Just a few weeks into the hurricane season, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, has declared the end of El Niño, the warm streak of water in the Pacific that influences global weather. That makes an already dire outlook for cyclones even more dangerous — in April, scientists forecasted five major hurricanes and 21 named storms in the North Atlantic alone — because El Niño tends to suppress the formation of such tempests.

NOAA now predicts a 65 percent chance of La Niña, which is favorable for cyclones, developing between July and September, when such events are most common. (La Niña is a band of cool water forming in contrast to El Niño’s warm band.) At the same time, sea surface temperatures remain extraordinarily high in the Atlantic — the kind of conditions that power monster storms.

The Atlantic is primed for a brutal hurricane season. But these cyclones aren’t just made of devastating winds and rains — they’re full of invaluable data that scientists will use to improve forecasting, giving everyone from local meteorologists to federal emergency planners better information to save lives.

Such insights would be particularly critical if, for instance, a hurricane rapidly intensifies — defined as an increase in sustained wind speeds of at least 35 mph in 24 hours — just before it reaches shore and mutates from a manageable crisis into a deadly one. “Those cases right before landfall, where people are most vulnerable, is the nightmare scenario,” said Christopher Rozoff, an atmospheric scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research who models hurricanes. “That’s why it’s of such great interest to improve this, and yet it’s been a huge forecasting challenge until somewhat recently.” (Which is not to say weaker storms can’t also be catastrophic — for instance, they might stall over a city and dump torrential rain.)

For such calamitous phenomena, hurricanes feed on a certain level of atmospheric boringness. El Niño suppresses the development of these storms by encouraging vertical wind shear, or winds moving at different speeds and directions at different elevations. That messiness tilts the vortex, interfering with a hurricane’s ability to spin up uniformly. The La Niña that could form this summer, on the other hand, decreases that wind shear in the Atlantic, providing ideal conditions for cyclones.

On the ocean’s surface, extremely high temperatures have already turned the Atlantic into a vast pool of fuel for hurricanes to start forming. When this water evaporates, the vapor is ingested by the storm, forming buoyant clouds that release heat and lower the atmospheric pressure. This draws in air to create wind, which spins up into a vortex.

If the sea is warm enough, and vertical wind shear is low enough, a hurricane has the potential for rapid intensification. “The atmosphere usually drives the bus when it comes to rapid intensification — it is definitely something that is on my mind this hurricane season,” said Eric Blake, a senior hurricane specialist at the NOAA’s National Hurricane Center. “When you have extremely warm waters, it just increases the chances that it can occur in areas that maybe it wouldn’t normally occur in.”

Last year, several hurricanes quickly strengthened, including Hurricane Idalia, which tore into communities along the Florida coast. Over in the Pacific, Hurricane Otis evolved into a monster with stunning speed before devastating Acapulco, Mexico. “That storm intensified from a tropical storm to a Category 5 in just over a 24-hour period,” said Rozoff. (For context, a Category 1 hurricane has sustained winds of at least 74 mph, while Category 5 is at least 157 mph.) “We’ve seen improvements in forecasting and our ability to capture these events, but that particular forecast still fails, unfortunately, by the numerical models. None of them were foreseeing this intensification to such an extreme storm that would be so damaging.”

Because blistering strengthening involves highly complicated interactions between the sea and the sky, it’s notoriously hard to predict. As the planet warms, hotter oceans provide more energy for hurricanes, and complex ripple effects across the atmosphere might also reduce wind shear along the Atlantic coast going forward. Indeed, a paper published last year found an explosion in the number of rapid intensification events close to shore in recent decades.

Not only are scientists trying to parse why a particular hurricane would quickly intensify in 2024, they have to figure out what to expect as the oceans get hotter and hotter, providing more and more cyclone fuel. It’s a moving target, one made of torrential rain and 160 mph winds. “We have a great database of weather that happens now, and we don’t necessarily have a great database of weather that will happen in the future,” said Sarah Gille, a physical oceanographer at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. “So extreme storms are one window into that, that can help us get a better picture of what we might see.”

As hurricanes spin across the Atlantic this summer, scientists will be ready. They can fly “Hurricane Hunter” aircraft into the cyclones while collecting oodles of data like wind speed, pressure, and humidity. (That’s another factor in major hurricanes: They love humidity and hate dry air.) They’ll then feed this data into models that try to predict rapid intensification. Increasingly, scientists are using artificial intelligence to supercharge these algorithms, for instance training an AI to recognize patterns in satellite images of a hurricane, or precipitation in the core of the storm, to predict whether it will rapidly intensify or not.

Whether from an aircraft or a satellite, every new observation of these cyclones feeds into models that are getting better at understanding why hurricanes behave the way they do. That means better information for coastal cities to decide whom to evacuate and when. “We’ve gotten a lot of good data at a time when the technology is improving, so I think that’s why we’ve made so much progress,” said Rozoff. “Every case of rapid intensification before landfall — whether forecasted well or not — is a tragedy, or at least a serious challenge for humanity. But it has provided us some good data as well.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How this summer’s brutal hurricanes might one day save lives on Jun 20, 2024.

A new study has found that approximately one in four households in the United States has soil lead levels exceeding the new U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s limit of 200 parts per million (ppm). The previous screening level was 400 ppm.

For households that have multiple sources of lead exposure, the guidance level was lowered to 100 ppm, a press release from the American Geophysical Union (AGU) said. The researchers found that almost 40 percent of households in the United States exceeded that level.

“Based on a wide network of citizen-science collected household soil samples, we find that nearly one in four households may now contain a soil lead hazard based on this new, more protective standard,” the authors of the study wrote. “Unsafe levels of lead exposure [have] occurred in many communities across the United States, with much of the burden resting on lower income communities, and communities of color. Lead exposure is prevalent due to past lead emissions and the substantial legacy lead loads that remain in soils and structures within communities.”

A lead concentration limit for human blood was first set by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention back in 1991, AGU said. However, the lead screening level for soil set by the EPA was the same for more than three decades until early this year. By then, some states like California — which has the lowest limit at 80 ppm — had established their own guidelines.

In the study, the authors said the delay was likely due to “the immensity and ubiquity of the problem.”

“The scale is astounding, and the nation’s lead and remediation efforts just became substantially more complicated,” the authors said. This is because the lower limits mean the EPA needs to let people know the steps to take if their soils are over the appropriate threshold.

To find out how many households exceeded the updated guidelines, the researchers looked at their database of residential soil samples — 15,595 of them — collected from gardens, yards, alleys and other residential locations across the contiguous U.S.

They found that about a quarter of the samples exceeded the new limit of 200 ppm, whereas just 12 percent had exceeded the higher threshold of 400 ppm. That means about 29 million households across the country exceed the new lead limits.

For households with multiple exposure sources — like lead pipes and soil contaminated with lead — the EPA guidance level is 100 ppm. According to the study, 40 percent of households were above that limit, bringing the number to nearly 50 million.

“I was shocked at how many households were above the new 200 ppm guideline,” said Gabriel Filippelli, lead author of the study and an Indiana University biochemist, in the press release. “I assumed it was going to be a more modest number. And results for the 100 ppm guideline are even worse.”

The study, “One in Four US Households Likely Exceed New Soil Lead Guidance Levels,” was published in the journal GeoHealth.

Lead, a heavy metal, can build up in the human body and have toxic effects. It can come from old paint and water pipes, industrial pollution and remnant gasoline. Most lead exposure today is from contaminated dust and soils that remain after the removal of lead-tainted infrastructure.

In the U.S., there is a historically disproportionate burden of lead exposure in communities of color and those with lower incomes due to discriminatory practices such as redlining — a real estate practice where financial services were withheld in neighborhoods with higher numbers of ethnic and racial minorities. Lead exposure has been linked with lower educational outcomes in children.

Contaminated soils are usually remediated with traditional “dig and dump” removal, but this method is costly and requires an area to first be put on the remediation National Priority List, which can be a years-long process. The researchers calculated that the remediation of all contaminated households using the “dig and dump” method would cost from $290 to $1.2 trillion.

The process of burying lead-contaminated soil with roughly a foot of mulch or soil — called “capping” — is a less expensive option. The installation of a geotechnical fabric barrier is also a potential solution.

Filippelli pointed out that most soil lead contamination sits in the first 10 to 12 inches underground, so either of these methods dilutes or covers up the issue to a level that is acceptable.

“Urban gardeners have been doing this forever anyway, with raised beds, because they’re intuitively concerned about the history of land use at their house,” Filippelli said. “A huge advantage of capping is speed. It immediately reduces exposure. You’re not waiting two years on a list to have your yard remediated while your child is getting poisoned. It’s done in a weekend.”

Filippelli emphasized that despite the time and effort it takes to cap soil, the costs are likely outweighed by the health benefits. There is still a lot that is unknown about the sustainability and lifespan of capping, Filippelli added, and that will be a focal point of research in the future.

“I’m really optimistic,” Filippelli said in the press release. “Lead is the most easily solvable problem that we have. We know where it is, and we know how to avoid it. It’s just a matter of taking action.”

The post 1 in 4 Yards in U.S. Exceeds New EPA Limits for Lead Levels in Soil, Study Finds appeared first on EcoWatch.

A new United States federal government report has found that the hydropower dams on the Columbia River have flooded villages and disrupted ways of life, while continuing to harm Indigenous Peoples of the Pacific Northwest.

The report, Historic and Ongoing Impacts of Federal Dams on the Columbia River Basin Tribes, was released by the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI). It is part of an agreement made by the Biden-Harris administration to acknowledge the harms inflicted upon Pacific Northwest Native American Tribes and restore wild salmon to the Columbia River Basin, a press release from the DOI said.

“Since time immemorial, Tribes along the Columbia River and its tributaries have relied on Pacific salmon, steelhead and other native fish species for sustenance and their cultural and spiritual ways of life. Acknowledging the devastating impact of federal hydropower dams on Tribal communities is essential to our efforts to heal and ensure that salmon are restored to their ancestral waters,” said U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland in the press release.

The report details the historic, cumulative and ongoing impacts 11 dams constructed on the Snake and Columbia Rivers have had on eight Columbia River Basin Tribes, reported The Seattle Times.

The federal report also gives recommendations for ways the U.S. government can further its responsibilities to Tribes through the acknowledgment and integration of these damaging impacts into future actions, the press release said. It is the first time the federal government has provided a comprehensive analysis of the ongoing harms caused by the dams to Pacific Northwest Tribes.

As part of the agreement made last year between the U.S. and the Tribes, the federal government pledged $1 billion for the restoration of wild salmon and the facilitation of green energy production, but did not provide for dam removal, The Seattle Times reported.

The report “fulfills a commitment made by the Department as part of stayed litigation in National Wildlife Federation v. National Marine Fisheries Service,” the press release said. “In December 2023, the Administration also announced an historic agreement to restore salmon populations in the Lower Basin, expand Tribally sponsored clean energy production, and provide stability for communities that depend on the Columbia River System for agriculture, energy, recreation and transportation.”

The report looks at how, in less than 100 years, Native Americans in the Columbia River Basin — and the river itself — were tragically changed by the dams, reported The Seattle Times. It also asks federal agencies to recognize Tribal expertise in the restoration of wild salmon runs while taking immediate and substantial next steps.

“To have the recognition of not just historical traumas but also present has been personally impactful,” said Jeremy Takala, Yakama Nation councilmember, as The Seattle Times reported. “I live over here in Goldendale, like lots of [T]ribal folks living along the river and still dealing with the impacts… There are still unfulfilled obligations.”

As many as 16 million wild steelhead and salmon once made their return journey to Pacific Northwest tributaries annually, providing sustenance for Tribal members and more than 130 species of wildlife.

“Since time immemorial, members of these Tribes and their ancestors stewarded these native species and relied upon their abundance as the staples of their daily diets and ceremony,” the press release said. “The construction of large multipurpose, hydroelectric dams throughout the Columbia River Basin beginning at the turn of the 20th century blocked anadromous fish from migrating into certain reaches of the Basin, flooded thousands of acres of land, sacred sites, and ancestral burial grounds, and transformed the ecosystem. As a result, many Tribal communities lost access to anadromous fish in their communities.”

The report specifies how the traumatic effects of the dams have altered traditional diets and taken away the ability of Tribal members to fully exercise their ancient ways of life, while fundamentally changing how they teach and raise their children with the cultural and spiritual traditions centering around these fish.

Recommendations for how the federal government can further its trust responsibility while making the Columbia River Basin healthy and resilient for future generations include fully taking into consideration and integrating the inequities suffered by the Tribes into future reviews of the National Environmental Policy Act; continuing to pursue co-management and co-stewardship agreements; moving forward with the consolidation of Tribal homelands; and integrating Indigenous knowledge into federal decision making.

“As part of our ongoing commitment to honoring our federal commitments to Tribal Nations, the Interior Department will continue to pursue comprehensive and collaborative basin-wide solutions to restore native fish populations, empower Tribes, and meet the many resilience needs of communities across the region,” Haaland said in the press release.

The post U.S. Government Publishes First Thorough Analysis of Harm Done to Indigenous Groups by Columbia River Dams appeared first on EcoWatch.

As modern humans find ways to adapt and build resiliency to anthropogenic climate change, one art exhibition is looking to the past to uncover how the 17th century Dutch acclimated themselves to extreme weather.

The Getty Center, a museum in Los Angeles, opened an exhibition on May 28 titled On Thin Ice: Dutch Depictions of Extreme Weather, which features Dutch artists’ works from the 1600s.

The exhibition, on display through Sept. 1, explores the everyday resilience to the extreme weather during a time period nicknamed the “Little Ice Age.” According to the museum’s representatives, this time period consisted of particularly harsh winters as well as cooler-than-usual summers.

While it wasn’t a massive ice age on a global scale, the Little Ice Age lasted hundreds of years, from around 1300 to 1850 and affected much of the Northern Hemisphere, particularly Europe. This was caused in part by volcanic activity and changing wind patterns and ocean currents, and it led to long winters, with frequent and heavy snowfall.

While the Dutch struggled, facing extreme weather such as powerful storms and flooding, historians have uncovered more and more evidence that the Dutch in particular were able to build resilient communities that helped provide food to disadvantaged families, improve infrastructure, further scientific advancements and more, according to an essay in Aeon.

While the Industrial Revolution — and the emissions that skyrocketed since — didn’t begin until the 18th century, long after the artworks in the On Thin Ice exhibition were created, humans today can still relate to how people throughout history adapted to more natural bouts of climate change and extreme weather, the exhibition suggests.

A sense of community and innovation helped people of the past adapt to the extreme weather they were facing. In the Netherlands, this looked like adapting to frozen waterways that remained icy into spring with improved icebreaking tools and greasing ships and strengthening ship hulls to combat icy waters, as The Washington Post reported. If the ice couldn’t break down, communities would pivot and host ice fairs to attract visitors and generate income. During this time, the Dutch also invested in charities and established insurance policies to offer more protections against the many things that could go wrong in the face of extreme weather.

The Getty Center exhibition includes around 40 drawings and paintings by Dutch artists, with a highlight on works by painter Hendrick Avercamp.

The entrance to the exhibition reads, in part, “In the seventeenth century the Dutch Republic experienced a period of political stability, economic prosperity, and great technological advancement. A complex system of levees, canals, and windmills protected the Netherlands from the encroaching sea and transformed marshland into highly fertile tracts of farmland.”

“Astute observers and critics of their time, artists underscored the fundamental uncertainty of climate conditions, and their works offer opportunities to reflect on our current environmental crises,” the exhibition introduction continues.

One painting by Avercamp, “Winter Landscape With Skaters,” was painted during one of the harshest winters of the time period. You can see moored boats partially frozen in a thick sheet of ice, and some people in the foreground standing near a large hold for ice fishing. Some people are walking together, some people are playing games on ice and others are hauling goods.

“Winter Landscape With Skaters” by Hendrick Avercamp. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam / public domain

Another work from Avercamp, “A Winter Scene with Two Gentlemen Playing Colf,” shows people enjoying time outdoors, whether they’re just standing on ice talking to one another or sledding and skating. Two people at the foreground of the painting engage in a game of colf, a Dutch game with similarities to golf and hockey.

“A Winter Scene with Two Gentlemen Playing Colf” by Hendrick Avercamp. Getty Museum

Another work, “January” by Jan van de Velde, shows a community coming together for merriment, like skating on a frozen lake and walking in groups on an outdoor path, despite the cold temperatures.

“January” by Jan van de Velde. UCLA Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts,

Hammer Museum, Rudolf L. Baumfeld Bequest

The Dutch were able to prosper economically during the Little Ice Age, in part by providing goods and supplies to other countries. We can get a glimpse of their work amid freezing temperatures in “Winter Landscape,” an artwork by Nicolaes Molenaer. In the piece, people are depicted moving goods across ice, which must be very thick and frozen to hold the weight of horse-drawn carriages moving supplies. People in the drawing are bundled in coats and hats.

“Winter Landscape” by Nicolaes Molenaer. National Museum in Warsaw / Wilanów Palace / public domain

In “A Winter Scene” by Hendrik Meyer, there are displays of harsh winter and hard work, yet comfort and warmth. Snow is piled up on a roof and the surrounding landscape, and workers are chopping and hauling wood and transporting people in carriages. People have flushed cheeks, and a mother and child stand in the doorway of a home with smoke blowing out of the snowy chimney.

“A Winter Scene” by Hendrik Meyer. Getty Museum

On the opposite site of “A Winter Scene,” the exhibition includes another work by Hendrik Meyer titled “A Summer Scene.” Here, people are tending to animals and agricultural work. According to the Getty Center, details like animals in the shade, dogs drinking water, and women in their bare feet may indicate hot weather. In the far distance, the viewer can spot windmills.

“A Summer Scene” by Hendrik Meyer. Getty Museum

These are just a handful of works on display in the exhibition, but they collectively show a range of families and strangers who are both working hard for the community and indulging in leisure time and recreation, despite facing extreme weather.

“During a period of extended cold in the 17th century, a number of remarkable Dutch artists created a genre of paintings and drawings that capture the icy landscapes and extreme living conditions of climate gone awry,” Timothy Potts, Maria Hummer-Tuttle and Robert Tuttle Director of the Getty Museum, said in a press release. “There are obvious resonances with the opposite extreme we face today in the rising temperatures across much of the globe.”

The old adage goes that history repeats itself, and while the current climate crisis often comes with unprecedented events, this art exhibition reveals some hope in how humans can work together to adapt to climate change.

During the Little Ice Age, the Dutch, as depicted in the artworks, became important purveyors of goods to other countries, dedicated themselves to hard work for community betterment, and even participated extensively in charitable acts, as explained by Anne McCants, a history professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. They adapted so well that their advancements during the Little Ice Age led to the Dutch Golden Age.

Rather than be passive bystanders to the worst impacts of the climate crisis, humans today can and should collaborate to work on slowing climate change and undoing some of the damage we’ve done to the planet. Like the people of the past, we’ll need to work together and tap into innovation and ingenuity to overcome the struggles we face.

“Today’s global climate crisis is an ongoing issue affecting current and future generations, and often inspiring the work of contemporary artists. This exhibition offers a glimpse at how Dutch artists in 1600s presented such topics,” said Stephanie Schrader, curator of drawings at the Getty Museum. “Not only will it give visitors a better understanding of the past, but it will also provide an example of how adaptation is our only hope for the future.”

The post Museum Exhibit Draws Parallels Between ‘Little Ice Age’ Resiliency and Modern Climate Crisis appeared first on EcoWatch.

The State of Global Air Report 2024 has revealed that an average of around 2,000 children, aged 5 and younger, are dying every day from poor air quality.

The study, by the Health Effects Institute (HEI) in partnership with UNICEF, linked 8.1 million deaths of people of all ages in 2021 to air pollution. The report determined that in 2021, around 709,000 deaths of children under 5 years could be connected to air pollution, making poor air quality responsible for around 15% of global deaths of children 5 years and younger.

“We hope our State of Global Air report provides both the information and the inspiration for change,” HEI President Dr. Elena Craft said in a press release. “Air pollution has enormous implications for health. We know that improving air quality and global public health is practical and achievable.”

As The Guardian reported, air pollution is now the second biggest cause of death globally, behind high blood pressure. Air pollution has overtaken smoking and other tobacco use. For children, poor air quality is the No. 2 killer behind malnutrition.

“Despite progress in maternal and child health, every day almost 2,000 children under 5 years die because of health impacts linked to air pollution,” said UNICEF Deputy Executive Director Kitty van der Heijden. “Our inaction is having profound effects on the next generation, with lifelong health and wellbeing impacts. The global urgency is undeniable. It is imperative governments and businesses consider these estimates and locally available data and use it to inform meaningful, child-focused action to reduce air pollution and protect children’s health.”

According to the report, fine particulate matter pollutants, or PM2.5, was responsible for more than 90% of air pollution-related global deaths in 2021. Fine particulates can enter the lungs and blood stream, increasing risk of lung cancer, heart disease and stroke. Sources of PM2.5 include fossil fuel plants, industrial facilities, transportation, wildfires and even fuel combustion at home for activities like cooking and heating.

This year’s State of Global Air Report highlighted the deadly impacts of long-term exposure to ground-level ozone, which was linked to around 489,518 global deaths in 2021. In the U.S., ground-level ozone exposure contributed to around 14,000 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), more than the ozone-related COPD deaths in other high-income countries.

For the first time in the report’s history, the 2024 version includes data on nitrogen dioxide exposure. As HEI explained, nitrogen dioxide is a common pollutant from vehicle exhaust. It can also be emitted by fossil fuel and industrial plants. Nitrogen dioxide can contribute to asthma and other respiratory conditions, the report noted, and can also contribute to worsening ozone and fine particulate pollution.

Despite these findings, the report highlighted some good news, including that the disease burden from air pollution exposure in children has declined by around 35% from 2010 to 2021 as household air pollution has declined. Further, the air pollution-related death rate in children under 5 years has declined 53% since 2000, in part thanks to clean energy developments.

But more actions are needed to reduce air pollution and improve health outcomes for people around the world.

“This new report offers a stark reminder of the significant impacts air pollution has on human health, with far too much of the burden borne by young children, older populations, and low- and middle-income countries,” Dr. Pallavi Pant, HEI’s Head of Global Health at HEI, said in a statement. “This points sharply at an opportunity for cities and countries to consider air quality and air pollution as high-risk factors when developing health policies and other noncommunicable disease prevention and control programs.”

The post Air Pollution Linked to 2,000 Child Deaths per Day Globally appeared first on EcoWatch.

Elizabeth Mitchell received a notice from her commercial property insurance company in April that set off alarm bells.

Acadia Insurance, the insurer for the market, workspace, and wellness-center nonprofit she runs in West Cornwall, Connecticut, would no longer cover “bodily injury, property damage, or personal and advertising injury” from “contact with, exposure to, existence of, or presence of any ‘PFAS.’”

PFAS, as Mitchell soon discovered, is short for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, which appear in everything from clothing to cleaning products to cookware and are linked to a wide range of health risks. Since most of these toxic substances don’t break down and are now found in the blood of people all over the world, they’ve earned the nickname “forever chemicals.”

An increasing number of Connecticut towns have found forever chemicals in their water supplies, and for decades, the river that runs through Mitchell’s community has been contaminated by hazardous waste, leading to hundreds of millions of dollars in settlements. Now, if forever chemicals were found in the local water supply and someone sued Mitchell’s nonprofit for exposure, the operation would be at risk of bankruptcy.

“Places like us, you can’t get sued,” said Mitchell. “We definitely could not sustain a lawsuit.”

Mitchell, who is my mother, is one of thousands of business owners who could be getting notices that their insurers will no longer cover PFAS risks.

As concerns about the dangers of forever chemicals rise nationwide and lawyers warn of a deluge of “astronomical” lawsuits, commercial insurers are quietly eliminating liability coverage for these chemicals’ health and ecological consequences. Such coverage exclusions can leave small businesses on the line for costly litigation and victims without recourse for their medical costs from life-threatening PFAS exposure.

This trend “is definitely well underway,” said John Ellison, an attorney who works on behalf of insurance policyholders at the global law firm Reed Smith. “Certainly large portions of the insurance industry have decided that they’re not interested in selling liability insurance coverage for PFAS.”

Acadia Insurance declined to comment.

Companies are so worried about the cost of future PFAS litigation that they have labeled these chemicals the “new asbestos,” in reference to the once-ubiquitous building product whose links to cancer have led insurers to pay out nearly $100 billion in claims and sent dozens of firms into bankruptcy.

According to The New York Times, a defense lawyer recently warned at an industry conference that PFAS lawsuits could “dwarf anything related to asbestos” and that plastic-industry executives should “do what you can, while you can” to prepare for the onslaught of lawsuits “before you get sued.”

The elimination of PFAS insurance coverage is happening amid a nationwide crackdown on the chemicals. The Environmental Protection Agency just designated two widely used forever chemicals as “hazardous substances” and set the first-ever limits on these chemicals in drinking water. At least six states including Colorado, Kentucky, and Maine have enacted bills related to PFAS regulation this year.

Yet insurers’ fears about not being able to afford PFAS lawsuits may be misplaced, said Joanne Doroshow, executive director of New York Law School’s Center for Justice & Democracy. The industry had stored away more than one trillion dollars in surplus profits by the end of 2021 — an all-time high.

“We have insurance in order to protect us and we pay a lot of premiums to these companies with the expectation that when there is a claim they’ll pay it — and they don’t want to pay it,” Doroshow said.

First discovered in the late 1930s, forever chemicals have been commonly used across a wide range of consumer products since the mid-20th century. Not long after, major PFAS manufacturers like 3M and DuPont began conducting animal studies that uncovered disturbing findings, such as that a low daily dose of these chemicals could kill a monkey within weeks.

Yet the multinational conglomerates followed in the footsteps of Big Tobacco and hid the dangers of PFAS from the general public for more than 40 years. This included suppressing their own research and spending large sums to quietly settle lawsuits and fight federal regulations. A 2015 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention discovered that PFAS can be found in the blood of 97 percent of Americans.

In 1999, a West Virginian farmer filed a lawsuit against DuPont for contaminating his water with forever chemicals that allegedly killed his cattle. Since then, law firms have filed 9,800 suits alleging that forever-chemical exposure has led to cancer, heart damage, and other harms, resulting in almost $17 billion in settlements across 140 industries, according to a 2023 report by the Seattle-based consulting firm Milliman.

This March, a court approved a multibillion-dollar settlement from the multinational conglomerate 3M after the manufacturer was accused of contaminating public drinking water systems nationwide with forever chemicals that it had long been producing.

Now, insurers are working to limit their risk by dropping their PFAS coverage.

“Insurers, mindful of the high cost of defending and indemnifying their insured businesses’ PFAS risks, have begun modifying or reinterpreting business insurance policy provisions to mitigate their own coverage burden,” wrote attorneys from Minnesota-based Nilan Johnson Lewis, a law firm that represents businesses across a wide range of industries, in an online report.

Last year, the Insurance Services Office, a property and casualty insurance advisory organization that develops and publishes policy language for insurers, endorsed the exclusion of PFAS coverage. The organization’s endorsement provided language for insurers to “broadly exclude bodily injury, property damage and personal and advertising injury related exposures associated with PFAS” from business owners’ general liability insurance policies.

“Every sophisticated insurance company worth their salt would have [PFAS] on their radar as a potential concern,” said Chip Merlin, founder of Merlin Law Group, a litigation firm that advocates for the rights of policyholders. “They learned these lessons through things like asbestos.”

Over the years, hundreds of thousands of people across the United States have filed compensation claims for asbestos-related injuries, with the average settlement ranging from $1 to $2 million. In 2019, insurers saw $92 billion in losses from asbestos liabilities.

Erik Olson, a senior strategic director at the environmental advocacy group Natural Resources Defense Council, said PFAS lawsuits are more likely to target big businesses like DuPont or 3M, rather than neighborhood nonprofits.

So far, “the folks getting sued are those that have deep pockets, where [victims] can get substantial payouts,” said Olson.

But this does not mean small businesses are immune from future claims, said Ellison, the Reed Smith attorney. Ellison has represented larger businesses experiencing PFAS-related lawsuits, but suspects smaller businesses will experience similar litigation down the line.

“Any small business that is in the stream of commerce that PFAS is a part of, they are all subject to being sued,” he said. “Those companies have a big fight on their hands about whether they have insurance to defend those claims. It’s naive to say they’re not at risk.”

Along with stripping PFAS coverage from their plans moving forward, insurance companies are using long-standing pollution exclusions to avoid PFAS lawsuit payouts in other instances where business insurance policies did not explicitly bar PFAS liability coverage.

Pollution exclusions emerged in the early 1970s as a way for insurers to avoid big payouts following the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency and demands for companies to curtail and clean up pollution activities. Such exclusions have since become common in business insurance policies.

Now these exclusions are paying legal dividends for insurers aiming to avoid PFAS liabilities.

In 2022, a U.S. district court judge ruled that an insurer’s “total pollution exclusion” meant it did not have to cover a Dalton, Georgia, recycling facility after town residents alleged they were injured by PFAS chemicals the plant discharged into local waterways.

In a New York case that same year, an appellate court judge likewise ruled that insurers’ pollution exclusions meant they didn’t have to cover the maker of nonstick, heat-resistant materials in lawsuits claiming the manufacturer polluted groundwater with PFAS chemicals. The firm that represented the insurers called the ruling a “significant win for the insurance industry” and their client, who “was facing potentially enormous” expenses.

Some of these pollution exclusions also bar coverage for the testing and removal of pollutants from the environment, which could potentially be used to avoid payouts for PFAS cleanup efforts. Removing PFAS from the environment is incredibly costly: One study in Minnesota found that removing forever chemicals from wastewater streams in the state would cost between $14 and $28 billion over 20 years. The American Water Works Association estimates PFAS cleanup in drinking water nationally would amount to between $3.2 and $5.7 billion annually.

With this in mind, avoiding PFAS lawsuit payouts is par for the course for insurers, said Doroshow. “It’s about dumping risk,” she said. “That seems to be the business model of insurance companies.”

Yet Doroshow questions if PFAS pose a dire risk to insurers’ profits.

In the decade leading up to 2020, industry data showed that total commercial insurance payouts “had not spiked and generally tracked the rate of inflation and growth of population,” according to research by Doroshow and her colleagues. Meanwhile, insurers like Travelers — a major player in property and casualty insurance — hit their largest-ever profits this January, while premiums for policyholders soared.

Regardless, noted Doroshow and her collaborators, industry leaders “publicly spin the notion that the industry is financially beleaguered and cannot pay claims without significantly raising rates.”

While collusion to raise prices is illegal in many businesses, certain activities by insurers are exempt from federal antitrust laws, allowing them to share information about past losses and make future coverage and premium decisions accordingly.

“It’s really a function of a completely unregulated industry,” said Dorowshow. “They don’t have any federal regulation.”

The state of affairs is concerning for small business managers like Mitchell, who are now getting PFAS exclusion notices from their insurers.

“I’m the steward of this nonprofit and then the insurer sends me this letter, so what am I really covered for?” said Mitchell. “I like to believe that nobody would ever come in and sue, but I never know.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Forever chemicals are poisoning your insurance on Jun 19, 2024.

We can all take decisive action to protect the environment: reusing goods instead of sending…

The post Best of Earth911 Podcast: Globechain Founder & CEO May Al-Karooni On Expanding U.S. Reuse Markets appeared first on Earth911.

An increasing number of cities, counties, and states around the U.S. are committed to reducing…

The post It’s Time To Start Thinking About Net Zero Homes appeared first on Earth911.