Today, 30-year-old garment factory worker Khadiza Akhter lives in Savar, a suburb of Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh. Her small concrete house is clean and organized. Green shutters frame the windows, and clothes hang on lines outside her front door. A water spigot sticks out of the concrete next to the drying laundry, and the turn of a white plastic knob is all it takes for clear, clean water to rush out. Akhter calls it “a blessing of God.”

Akhter grew up some 180 miles south of Savar, in Satkhira — a district home to 2.2 million people on a river delta where, in recent decades, fresh water has become scarce. As sea levels rise, rivers dry up, and cyclones become more severe, Satkhira and the other low-lying districts that surround it have been among the first in the world to experience the sting of climate change-driven saltwater intrusion — the creep of seawater inland.

The memory of drinking water tainted with salt is burned into Akhter’s mind. “It felt like swallowing needles,” she told Grist and Vox in Bengali. “It doesn’t quench your thirst.” The water was so salty Akhter couldn’t properly clean herself with it. The sodium in the water prevented soap from forming bubbles and left powdery streaks on her skin as it dried. Her hair fell out, and she itched all over.

When she hit puberty, she had to wash her cloth menstrual pads in salty water. The monthly exposure to salt in her pads made her break out in sores. Akhter’s menstrual cycle became erratic. “One month, it showed up unexpectedly early, catching me completely off guard,” she said. “The next month, it seemed to disappear altogether.” She sought medical advice at the Shyamnagar Upazila Health Complex, the local hospital in Satkhira, but there was no long-term fix available to her, beyond stopping her period altogether with hormonal birth control pills. She left Satkhira a decade ago, when she was a teenager, and moved to Savar, known for having some of the cleanest water in Bangladesh.

When Akhter first arrived in Savar, she had trouble adapting to city life. She wasn’t used to eating food cooked on a gas stove, and went to extreme lengths to avoid it. “I used to buy biscuits or cakes from the office canteen and sometimes starved,” she said. But, Akhter, who knew she wanted children someday, pushed through. “All I ever wanted was a better life for my kids — a life where they wouldn’t have to worry about food or clean water,” she said.

Studies have shown that saltwater consumption has negative, long-lasting effects on nearly every stage of a woman’s reproductive cycle, from menstruation to birth. Akhter knew that if she stayed in Satkhira and started a family of her own there, she’d be putting herself in real danger. She’s not the only person in her region to leave in search of cleaner water. Millions of Bangladeshis have been internally displaced by flooding in the past decade, and experts say saltwater intrusion is one of the factors driving migration from rural regions of Bangladesh to urban centers.

In some ways, Akhter is one of the lucky ones. She got out of Satkhira before saltwater consumption led to high blood pressure, a hysterectomy, or worse. But the women, and other people with uteruses, who remain in Satkhira are suffering from reproductive health effects — issues that could become common elsewhere in the coming years. As sea levels rise and intensifying storms stress infrastructure systems along coasts around the world, salt water threatens to infiltrate freshwater drinking supplies in countries like Egypt, Italy, the United States, and Vietnam. The issue, a 2021 study stated, “has become one of the main threats to the safety of freshwater supply in coastal zones.” The health of women living in these areas is on the line.

Southwestern Bangladesh is accustomed to encroaching salt water. The region sits adjacent to where the Padma River — known as the Ganges in India — empties into the Bay of Bengal. Most of the Bangladesh delta is less than 2 meters, or 6.5 feet, above sea level, with some areas at or even below the tide line. When cyclones wheel into the bay, storm surge pushes salt water inland, flooding the area.

For generations, communities in Satkhira adapted to the ebb and flow that defines the delta ecosystem. In the late 1960s, when a catastrophic period of cyclone-driven storm surge submerged rice paddies in salt water and ruined livelihoods, Satkhira was one of the first districts in Bangladesh to turn those paddies into shrimp farms. Small-scale farmers took advantage of storm surge — trapping seawater in ponds and paddies to cultivate shellfish — and paved the way for other parts of coastal Bangladesh to do the same. Today, shellfish farms have expanded into roughly 675 square miles of land, most of it in southern Bangladesh. Annual shellfish exports are valued in the hundreds of millions of U.S. dollars, and the industry employs more than a million people directly, and millions more indirectly.

But the district’s legacy of hard-fought resilience is being undone by climate change.

Already, sea level rise has pushed the saline front more than 62 miles inland along the country’s 450-mile coastline. Climate models indicate that a 380-square-mile area in coastal Bangladesh, home to 860,000 people, could be under the high tide line by the end of this century. Every millimeter of sea level rise contributes to more expansive and intense saltwater intrusion in soil and freshwater resources.

Between 2000 and 2020, the country was hit by eight major cyclones. One of these powerful storms, 2007’s Cyclone Sidr, produced a 16-foot-high storm surge, rainfall, and tidal waves that flooded an area home to 3.45 million people. This week, a storm of similar proportions, Cyclone Remal, destroyed tens of thousands of homes and trapped thousands of people in the country’s low-lying areas. Nearly 40 percent of the country’s seaside soil already has salt in it, but storms like Sidr and Remal — the severe cyclones that are projected to become more common as climate change worsens — supercharge salinization by spreading unprecedented quantities of salt water deeper inland.

The Bangladeshi government has inadvertently contributed to the problem. In the 1960s, the government built a series of embankments around reclaimed land in southern Bangladesh. These areas, called polders, were meant to protect communities and agriculture from storm surge. But the embankments, which stand up to 13 feet high, are not tall enough to keep major surges out. Seven cyclones with storm surge of more than 13 feet hit Bangladesh between 1970 and 2008. Once the embankments have been overtopped, the seawater can’t flow out again.

The trend is made worse by the region’s growing shrimp and prawn industry. Black tiger shrimp, the main species of shrimp farmed in Bangladesh, thrive in brackish water — water that is saline but not quite as salty as seawater. When Satkhira began to embrace aquaculture and shrimp farming, the government neglected to study the potential risks of adding saline to freshwater ponds in order to make them suitable for shrimp farming. Over time, salt from the shrimp fields leached into ponds and other in-ground freshwater containers, further contaminating limited drinking water supplies. A 2019 report that tested salinity in 57 freshwater ponds in Satkhira found that 41 of them contained water that was too salty for drinking.

The Padma River, which carries fresh water from Nepal through India to Bangladesh, is another source of salinity. The river supplies much of the fresh water Bangladeshis use for irrigation, farming, freshwater fishing, and drinking. But the Padma’s flow into Bangladesh is restricted seasonally by India, which controls a dam in West Bengal called the Farakka Barrage. During dry periods, the flow of water coming into Bangladesh from India slows and the volume of river water going into the ocean weakens, allowing seawater to work its way up the Padma. When heavy rain falls, the river swells and salt water is pushed back out, expunging the river of its salinity and transforming the river back into a freshwater resource.

Families collect rainwater during the winter to use throughout the dry season, but climate change is scrambling those delicate calculations, too. The seasonal rains start later and stop earlier than they did a decade ago, and when it does rain, it rains harder. These compounding issues force Bangladeshis to pull more fresh water from groundwater aquifers, which are rapidly dwindling.

“The people are trapped,” said Zion Bodrud-Doza, a researcher at the University of Guelph in Canada who studies saltwater intrusion in Bangladesh. “When you don’t have water to drink, how do you live?”

In 2008, Aneire Khan, a researcher at Imperial College London, visited Dacope, a division of the Khulna district, which borders Satkhira in southwest Bangladesh. She met a gynecologist there who told her that an unusual number of pregnant women were coming to him with gestational hypertension and preeclampsia.

The former is defined as two separate blood pressure readings of greater than 140 over 90 in the second half of the pregnancy. The latter occurs when those high blood pressure readings are accompanied by high levels of protein in the urine.

Both conditions affect how the placenta develops and embeds into the uterine wall, said Tracy Caroline Bank, a maternal fetal medicine fellow physician at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. Patients with either condition “have a higher risk of things like a preterm delivery, of fetal loss,” she said, in addition to “a higher risk of the baby growing too small.” Premature babies are dealt a bad hand before they take their first breaths: Low birth weights are linked to poor development, cognitive impairments, cerebral palsy, and psychological disorders.

The gynecologist Khan spoke to said that high blood pressure readings, especially in women, were occurring with more frequency. Other medical professionals Khan spoke to in Khulna confirmed that observation. They thought salt water may be the culprit.

People who drink water with small amounts of salt in it can grow acclimated to moderate salinity over time. Khan, who was traveling between London and Bangladesh at the time, tasted the water in Khulna and was surprised to encounter immediate, undeniable salinity. It was “very, very salty,” she said. She conducted a survey of blood pressure levels in pregnant women living along the coast and compared the data to blood pressure in women living inland. More than 20 percent of the women living in coastal zones had been diagnosed with a hypertensive disorder, compared to less than 3 percent of women living in Dhaka. It was clear that a serious public health threat was growing along the coast, but no formal epidemiological study of saltwater intrusion and reproductive health in Bangladesh existed at the time. Khan set out to change that.

In 2011, three years after she spoke to the gynecologist in Khulna — the man who became her co-author — Khan published a study that showed that hypertension, or high blood pressure, in Dacope occurred seasonally. Out of the 969 pregnant women they analyzed, 90 presented with hypertension. In the wet monsoon months, heavy rains filled ponds with fresh water and diluted salt concentrations in rivers. During the dry season, lack of rainfall caused people to turn to other sources of drinking water that became steadily saltier over the course of the season. Of the 90 cases of gestational hypertension that Khan documented, 70 occurred during the months of November and April, the periods with the least amount of rainfall.

The World Health Organization recommends that adults consume no more than 5 grams of salt per day, about a teaspoon worth. Khan ultimately discovered that women in Dacope were getting more than three times that amount per day from their drinking water alone during the dry months.

Consumption isn’t the only way that salt water endangers women’s reproductive health. As Akhter learned as an adolescent, using salt water to wash cloth menstrual pads presents additional dangers. The water “doesn’t clean well,” said Mashura Shammi, a professor at Jahangirnagar University in Bangladesh who studies saltwater intrusion and the effects of pollutants on health. “The salt makes the cloth very hard,” she added, and can cause scratches in the vagina that lead to infection.

Other women in southwestern Bangladesh, particularly those who make a living working in shrimp aquaculture or fishing in the rivers, suffer even more intense health repercussions. Standing in salt water every day can produce chronic uterine infections and uterine cancer. The International Centre for Climate Change and Development, a research institute, interviewed women from Bangaldesh’s coastal zones and found anecdotal evidence of a host of saltwater-linked health outcomes. “I have cut off my uterus through surgery due to my severe infections,” one 32-year-old woman said. “And I am not the only one, there are many like me.” In the same report, a doctor from the Shyamnagar Upazila Health Complex said she had noticed “an increase in infertility, irregular periods, and pelvic inflammatory disease.” The doctor said that the majority of her female patients over the age of 40 have had hysterectomies or have undergone procedures to eliminate the lining of the uterus in order to lessen heavy menstrual bleeding.

Roughly 40 percent of the world’s population lives within 60 miles of a coast, and more than 100 countries are at risk of saltwater intrusion. By the end of 2019, 501 cities around the world had reported a saltwater intrusion crisis of some degree — more than a fifth of them home to more than 1 million people each. “Bangladesh isn’t the only country that’s going to be affected by salinity,” Khan said. “Vietnam, China, the Netherlands, Brazil — salinity in the coastal areas is going to be a huge issue, and is already a problem.”

The Mekong Delta, where the Mekong River flows into the ocean, is Vietnam’s breadbasket. Every year during the dry season, seawater flows up the mouth of the river from the South China Sea, turning the river salty for a month or two. People living in the delta — 20 percent of Vietnam’s population, many of them farmers — collect rainwater during the wet season to compensate for the seasonal salinity. But recent years have marked a departure from the norm. Yearslong droughts, more erratic rainfall patterns, and a network of Chinese dams upstream have produced a saltwater intrusion crisis in the Mekong River. The creep of saltwater upstream could lead to $3 billion in agricultural losses per year, and thousands of residents could see their drinking water cut off this year.

A similar story is unfolding in the Nile Delta in Egypt, where farmers are pumping groundwater to supplant increasingly salty water from the Nile River. Overreliance on coastal groundwater upsets the natural balance between freshwater aquifer and ocean. As groundwater levels drop, the pressure keeping salt water out weakens, allowing the ocean in. If aquifers are drained too quickly, and past a certain point, pumping water out of the ground can actually suck ocean water into the aquifers like a vacuum. Some 15 percent of the most fertile land in the Nile Delta is contaminated with salt water due to drought, sea level rise, and overpumping.

Nearly every solution to saltwater intrusion hinges on trying to keep seawater out of fresh water to begin with. Armoring coastlines with sea walls, levies, sandbags, and other hard infrastructure is the first line of defense in many countries. Those with water and money to spare can artificially “recharge” underground freshwater aquifers to preserve the natural tension between fresh water and salt water. Governments can also put restrictions on how much water farmers can pull from underground resources.

Preventative measures are more effective than fixes put in place after the fact. It’s nearly impossible to clean salt out of fresh water without the aid of expensive and energy-intensive desalination equipment, which most countries do not have. A medium-size desalination plant, which is an incredibly energy-intensive piece of infrastructure, costs millions of dollars to build and then millions more in annual operation costs. Even in very rich nations, runaway saltwater intrusion poses risks to infrastructure and people. Most water supply networks’ intake stations in the U.S., for example, are not outfitted with desalination technology. Once saltwater intrusion reaches those stations, they have to be shut off to avoid pulling the water in.

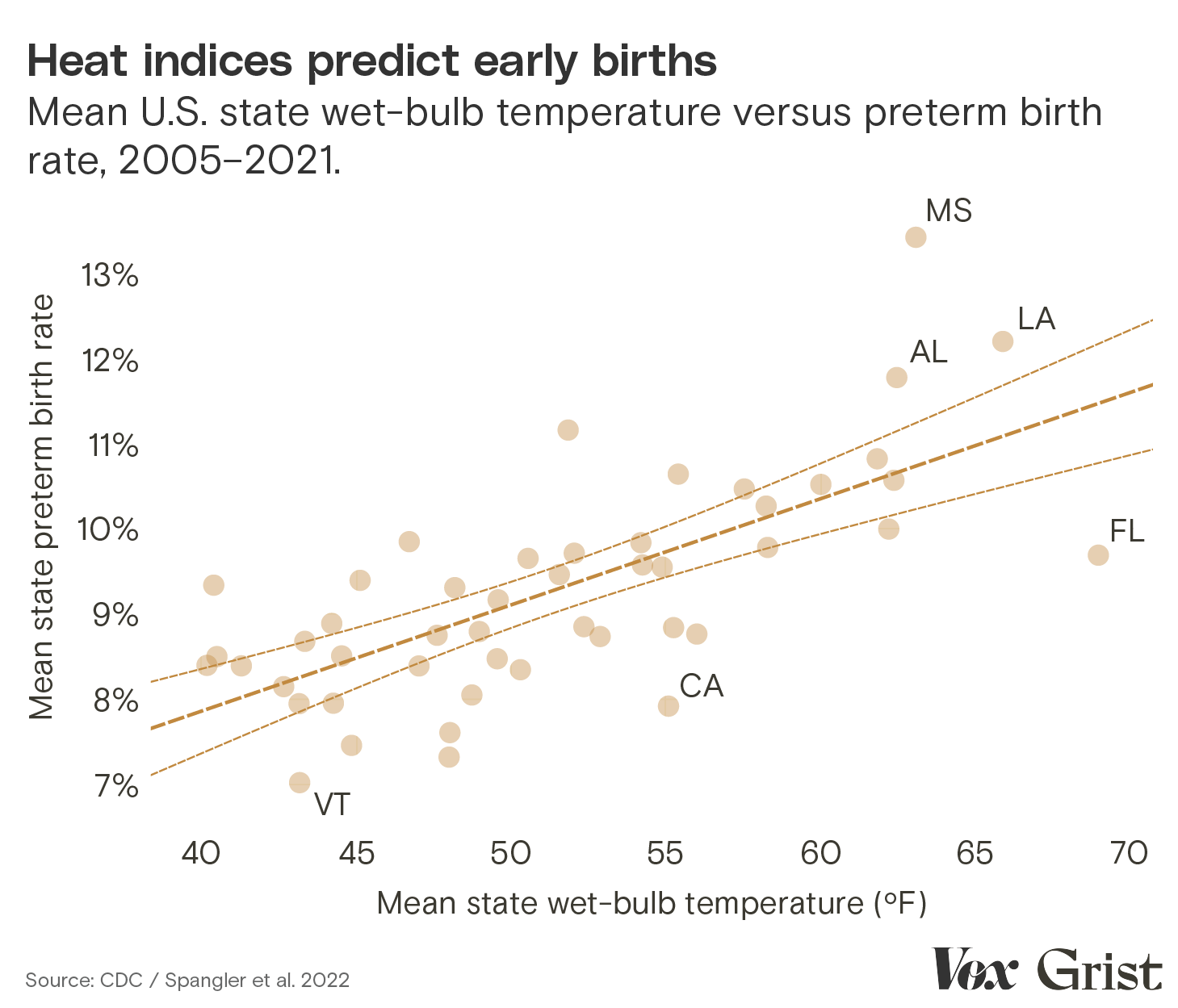

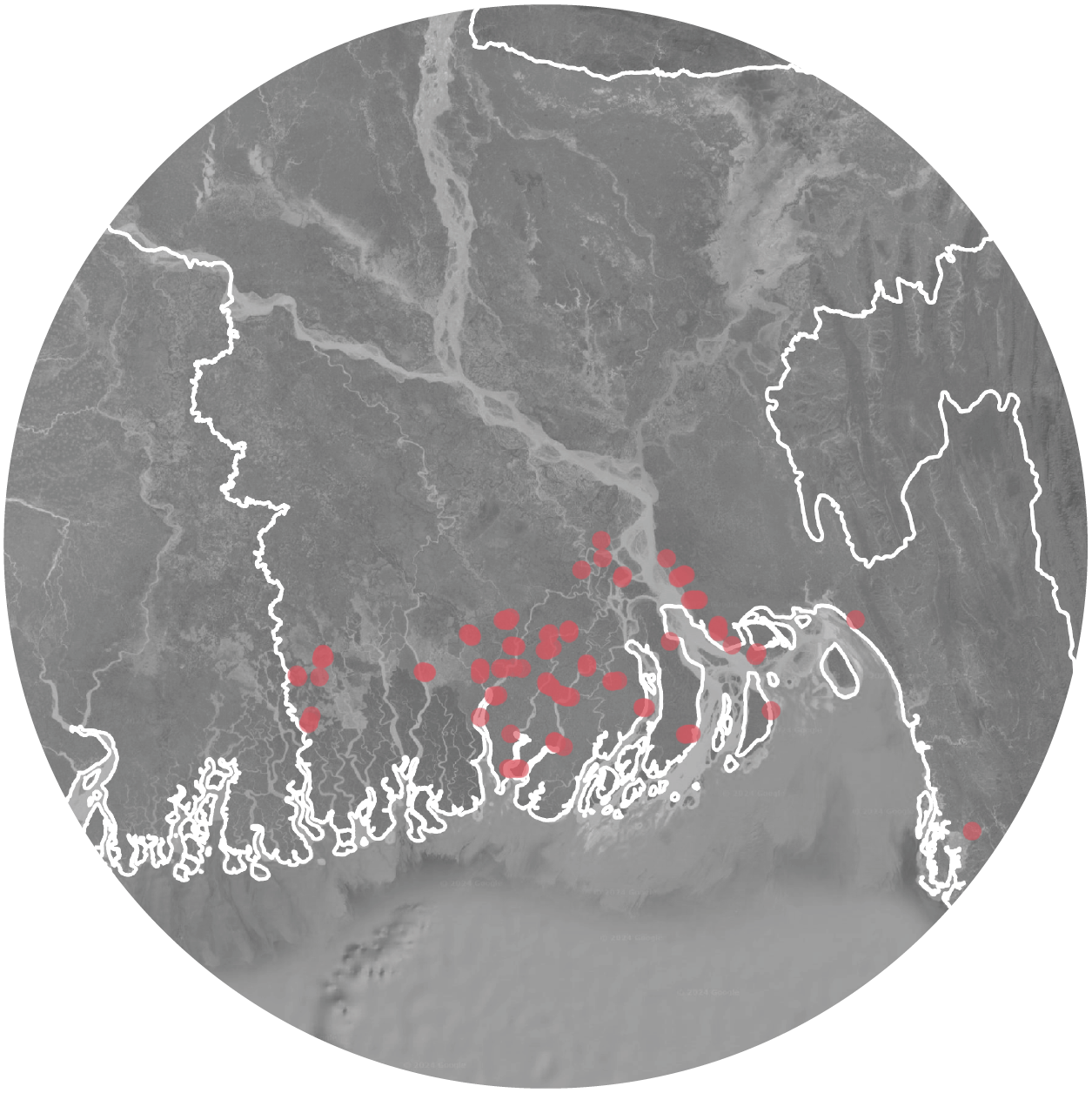

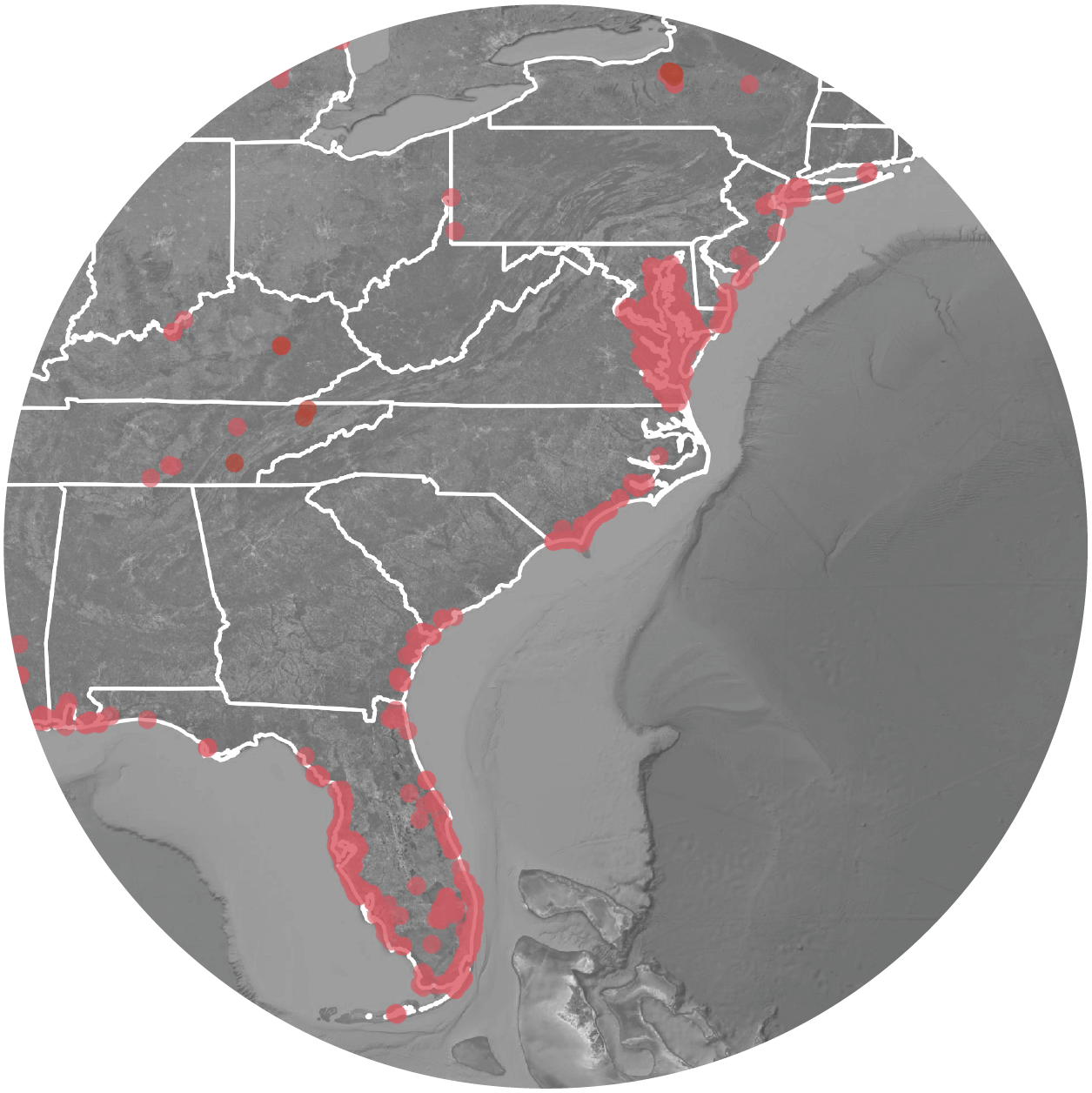

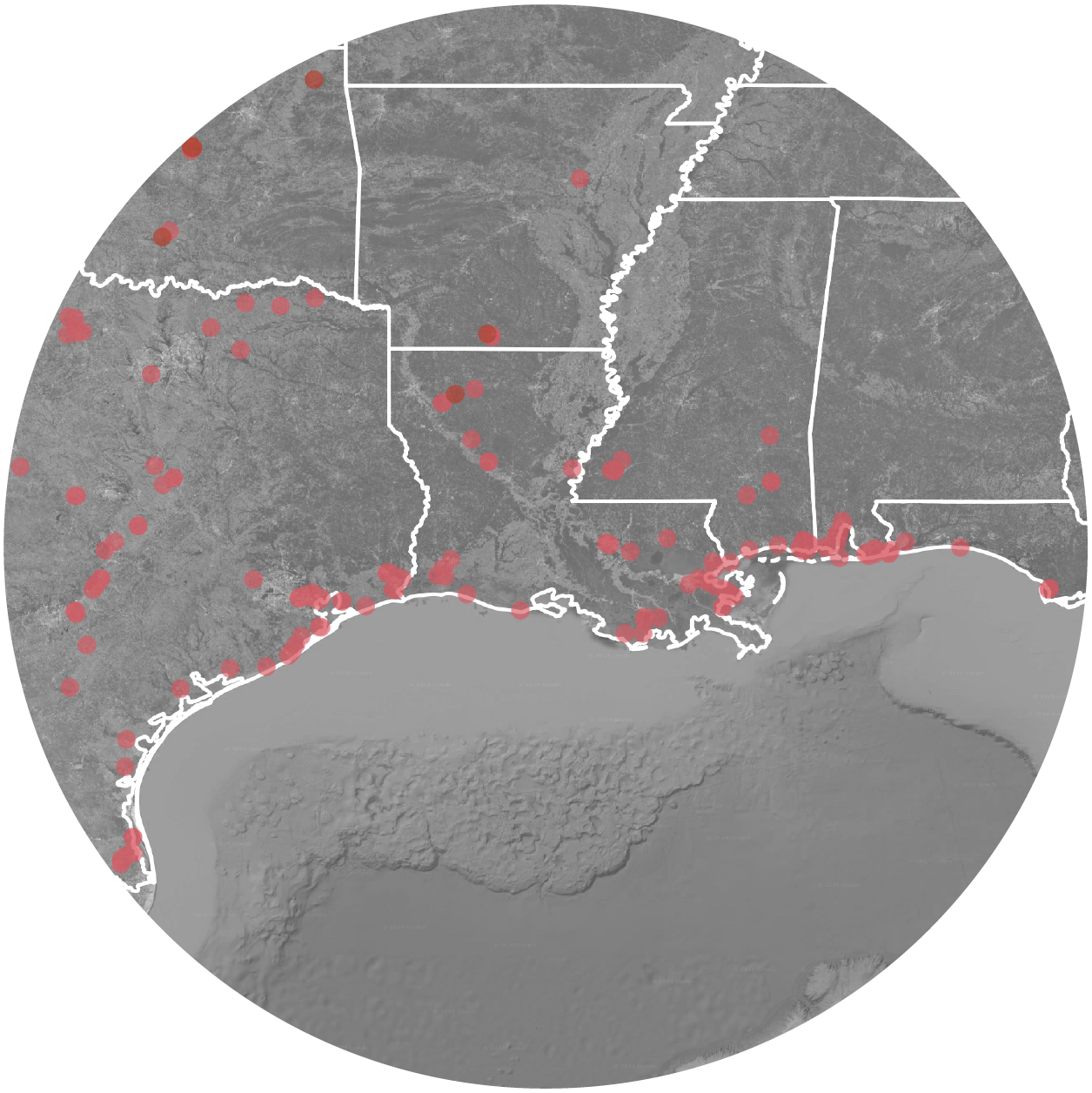

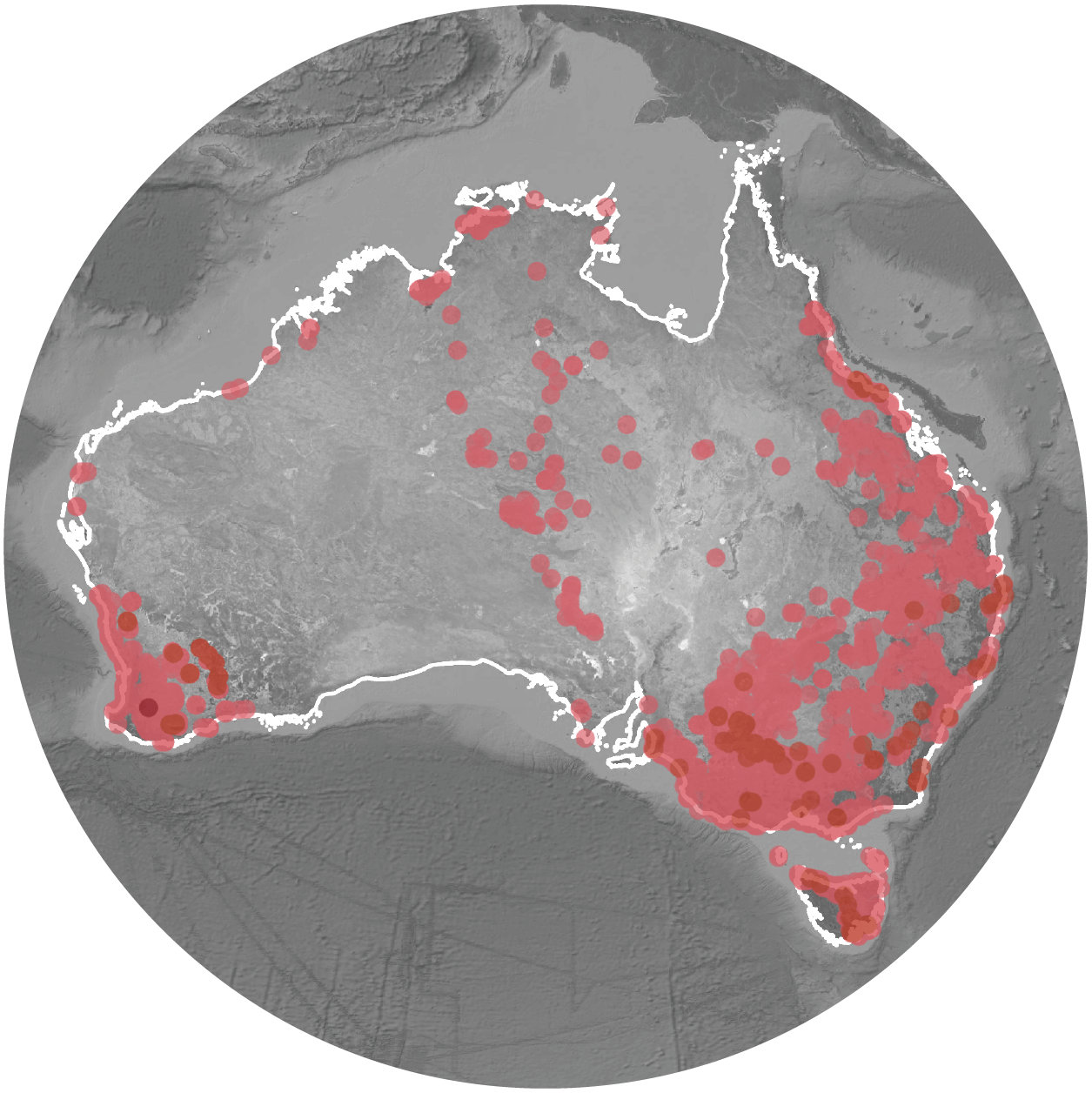

The creep of seawater inland

While global salinity monitoring is spotty, evidence of saltwater intrusion continues to grow.

Bangladesh

U.S. Atlantic Coast

U.S. Gulf Coast

Australia

Source: Thorslund & van Vliet 2020 | Clayton Aldern / Grist

Last year, drought in the Mississippi and the Ohio River valleys weakened the flow of water in the Mississippi River, and a massive wedge of seawater from the Gulf of Mexico started to creep north. As the wedge moved upstream along the bottom of the river, intake stations in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana, started sucking it in. More than 9,000 residents couldn’t drink water from their taps, and local officials started distributing bottled water. Rainwater eventually eased the drought and forced the wedge back toward the ocean. Water in Plaquemines Parish is currently safe to drink again, though experts warn salt water poses a long-term threat to drinking water in southeast Louisiana.

Saltwater intrusion “is an issue along most of the coastline in America,” said Chris Russoniello, a professor of geological sciences at the University of Rhode Island. California, Louisiana, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island are some of the states that are already confronting intrusion. But exactly how much of a threat it poses to communities “varies drastically from place to place,” Russoniello said. How much funding states direct to keeping saltwater intrusion at bay will determine the extent to which people feel the burden of intrusion. Many states already lack sufficient drinking water protections and infrastructure, particularly in low-income and minority areas. Saltwater intrusion is likely to exacerbate existing drinking water inequities. But, in general, the U.S. is much better equipped to address saltwater intrusion than other countries grappling with similar issues.

“The places where this will really be felt are places where the resources are not available,” Russoniello said. In Bangladesh, the government has tried to leverage billions in international and domestic resilience funding to try to protect communities in the southern parts of the country. The solutions often do more harm than good. The embankments are susceptible to breaching, shrimp and prawn farmers have further contaminated soil and drinking water with salt, and an expensive network of gates, locks, and sluices meant to control ocean water are decaying due to lack of regular maintenance. District governments and nongovernmental organizations distribute rainwater collection tanks to a small percentage of families every year, which provide some measure of relief. But none of these fixes are permanent.

“If the water is saline, you cannot make it fresh water in the blink of an eye,” Bodrud-Doza said. “People are trying to survive, but people need to leave.” Coastal Bangladesh and southeast Louisiana have that, at least, in common. Sea level rise will force a substantial portion of the population in both places to migrate inland. In areas where the encroaching tide, deadly storm surge, and widespread saltwater intrusion are inevitable, there will eventually be no option but retreat. “It’s something we need to think about as a society,” Russionello said. For the women already living on the front lines of a crisis that robs them of their health, reproductive organs, and pregnancies, retreating from the coastline is no longer a question of if, but how.

Akhter and her husband, Shamim, grew up in adjacent villages and met when they were children. They began dating in high school and later indicated to their families that they wanted to be married. Akhter was living in Savar when her marriage to Shamim was arranged by her parents. After they were married in a traditional ceremony in Satkhira, Akhter temporarily moved to Shamim’s village, where the salt levels in the drinking water were even higher than they had been in her home village. The couple tried purifying the water with aluminum sulfate powder and boiling the water with herbs. As a last resort, Shamim installed a water filter he obtained in Dhaka. Nothing helped.

Akhter permanently relocated to Savar with Shamim, and, soon after, became pregnant and gave birth to her first daughter, Miftaul. Two years later, she gave birth to a second healthy girl, Muntaha. At first, the family lived together in Savar. But Akhter and Shamim both work full time, and they couldn’t afford day care for both children. Their older daughter, Miftaul, who is now 5, lives in Satkhira with her grandparents for most of the year, and Akhter worries about the impact that saltwater intrusion will have on her young daughter’s life.

“It’s not ideal for her health, especially now that she’s growing,” Akhter said. “She already has trouble showering with salty water.” Miftaul has begun attending school in Satkhira, but Akhter and Shamim plan to bring her back to the city, where the schools and water quality are better, as soon as possible.

Akhter doesn’t want her children to relive a version of her own difficult childhood. A piece of her heart will always live in Satkhira, she said, but her future, and her daughters’ futures, are anchored in Savar. “I don’t want them to go through the struggles we faced.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Salt in the womb: How rising seas erode reproductive health on May 30, 2024.