It’s Earth Day 1990, and Meryl Streep walks into a bar. She’s distraught about the state of the environment. “It’s crazy what we’re doing. It’s very, very, very bad,” she says in ABC’s prime-time Earth Day special, letting out heavy sighs and listing jumbled statistics about deforestation and the hole in the ozone layer.

The bartender, Kevin Costner, says he used to be scared, too — until he started doing something about it. “These?” he says, holding up a soda can. “I recycle these.” As Streep prepares to launch her beer can into the recycling bin, Costner cautions her, “This could change your life.”

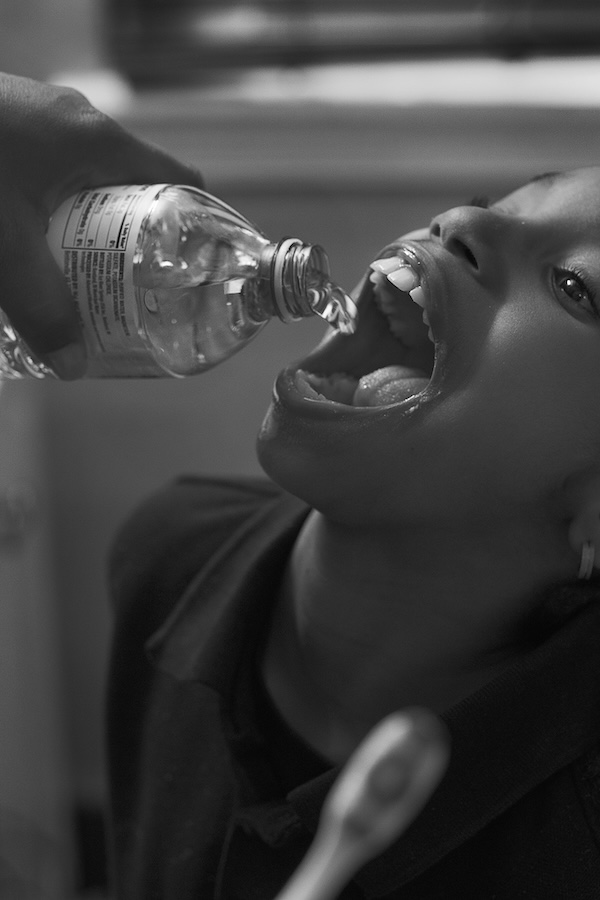

Recycling, once considered the domain of people with “long hair, granny glasses, and tie-dyed Ts,” as the Chicago Tribune described it at the time, was about to go mainstream. The iconic chasing-arrows recycling symbol, invented 20 years earlier, was everywhere in the early 1990s. Its tight spiral of folded arrows seemed to promise that discarded glass bottles and yellowing newspapers had a bright future, where they could be reborn in a cycle that stretched to infinity. As curbside pickup programs spread across the United States, the practice of sorting your trash would become, for many, as routine as brushing your teeth — an everyday habit that made you feel a little more responsible.

What no one anticipated was just how emotionally attached people would become to recycling as the solution to America’s ugly trash problem. When the chasing arrows’ promise of rebirth was broken, they could get angry. One cold winter day in 1991, people in Holyoke, Massachusetts, chased after garbage trucks, yelling for them to stop, after the drivers had nabbed their sorted glass, cans, and cardboard from the curb. Strained by an influx of holiday-related trash, the city had instructed workers to forgo recycling and just throw everything away.

Today, the recycling icon is omnipresent — found on plastic bottles, cereal boxes, and bins loitering alongside curbs across the country. The chasing arrows, though, are often plastered on products that aren’t recyclable at all, particularly products made of plastic, like dog chew toys and inflatable swim rings. Last year, the Environmental Protection Agency said that the symbol’s use on many plastic products was “deceptive.”

Recycling rules can be downright mystifying. For years, people were told pizza boxes were too greasy to be recycled, but now many recycling centers accept them. Some cities accept juice boxes lined with invisible layers of aluminum and plastic; others don’t. And do the screw-on caps stay on plastic bottles or not? Recycling experts ask people to do a “little bit of homework” to figure out what their local recycling system can handle, but since households have hundreds of items with different packaging to keep track of, that’s asking a lot.

The resulting confusion has made a mess of recycling efforts. Plastic wrap tangles around sorting equipment at recycling facilities, shutting down operations as employees try to cut it out of the equipment. Huge bales of paper shipped overseas can contain as much as 30 percent plastic waste. “Contamination is one of the biggest challenges facing the recycling industry,” the EPA said in a statement to Grist. It takes time and money to haul, sort through, and dispose of all this unwanted refuse, which makes recycling more of a burden for city budgets. Many cities have ended up cutting costs by working with private waste companies; some don’t even bother trying at all. About a quarter of Americans lack access to any recycling services.

The difficulty of recycling plastic can make the chasing-arrows symbol near meaningless, with environmental groups calling plastic recycling a “false solution.” Only around 5 percent of plastic waste in the United States gets shredded or melted down so that it can be used again. Much of the rest flows into landfills or gets incinerated, breaking down into tiny particles that can travel for thousands of miles and lodge themselves in your lungs. Plastics threaten “near-permanent contamination of the natural environment,” according to one study, and pose a global health crisis, with plastic chemicals linked to preterm births, heart attacks, and cancer.

So where did the three arrows go wrong? The trouble is that their loop has ensnared us. If some recycling is good, the thinking goes, then more recycling is better. That creates enormous pressure for packaging to be made recyclable and stamped with the arrows — regardless of whether trying to recycle a glass bottle or plastic yogurt container made much sense in the first place. David Allaway, a senior policy analyst at the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality, says that the facts just don’t support the recycling symbol’s reputation as a badge of environmental goodness. “The magnetic, gravitational power of recycling,” he said, has led “policymakers and the public to just talk more and more and more about recycling, and less and less and less about anything else.”

Getty Images

Harold M. Lambert / Getty Images

In the spring of 1970, an estimated 20 million Americans — 10 percent of the population — showed up for the first Earth Day, taking part in rallies, marches, and teach-ins, calling for clean air and clean water. Pollution had pushed its way into the national conversation. The year before, oil-soaked debris had caught fire in the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland, sending flames towering five stories high, and a drilling accident in Santa Barbara had spread an oil slick over more than 800 square miles of water. Smog regularly clouded skies from Birmingham, Alabama, to Los Angeles, dimming cities in the middle of the day.

The idea of recycling seemingly burst onto the scene in 1970. Earth Day organizers educated people about the value of sorting through their trash and advocated for community recycling programs. People would gather up their bottles and cans in plastic crates and bags and drive to designated sites to drop them off, sometimes earning a few bucks in return. “The environmental crisis has come into the public consciousness so recently that the word ‘recycle’ doesn’t even appear in most dictionaries,” the environmentalist Garrett De Bell wrote a couple weeks before the Earth Day event. He pitted recycling as “the only ecologically sensible long-term solution” for a country “knee-deep in garbage.”

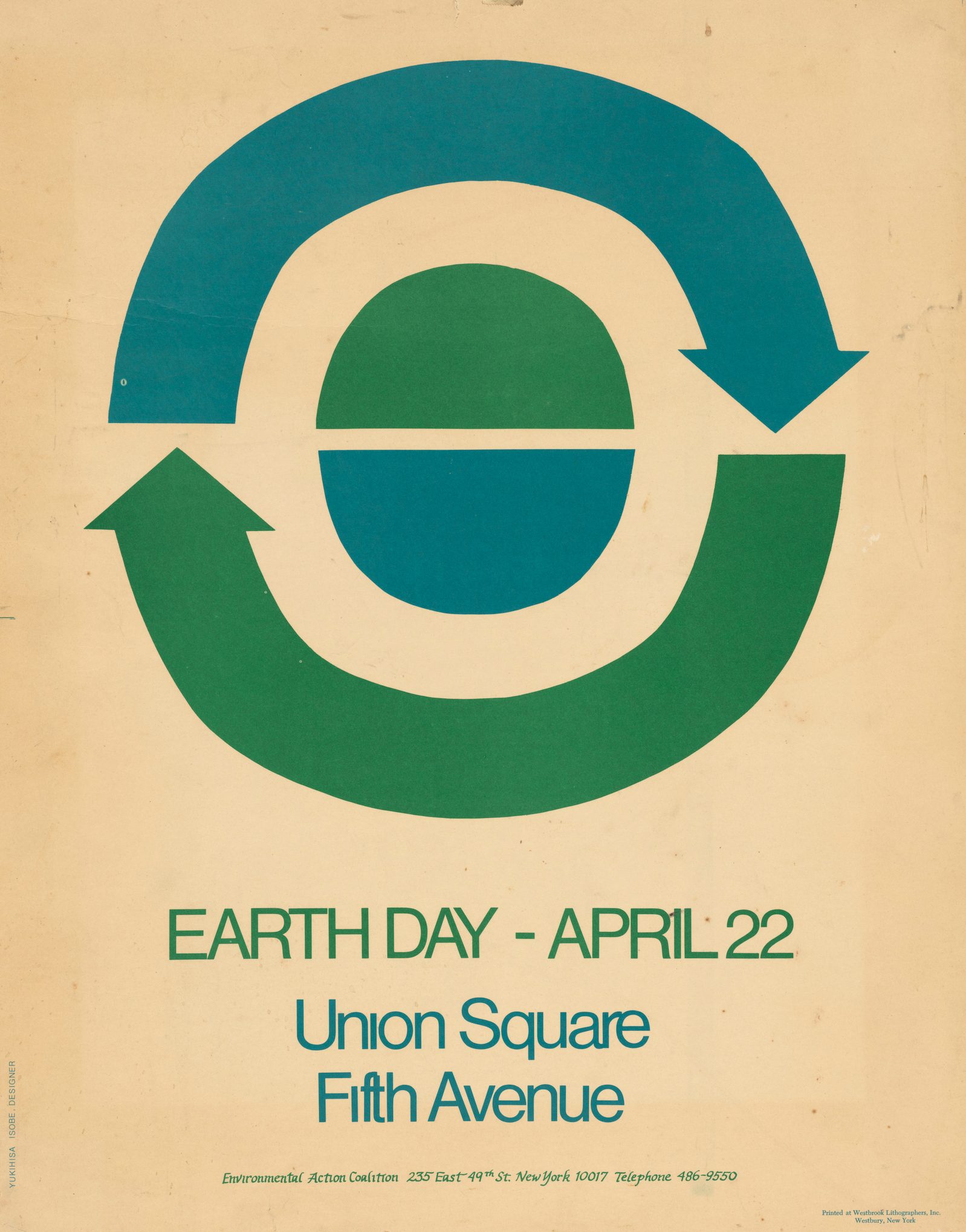

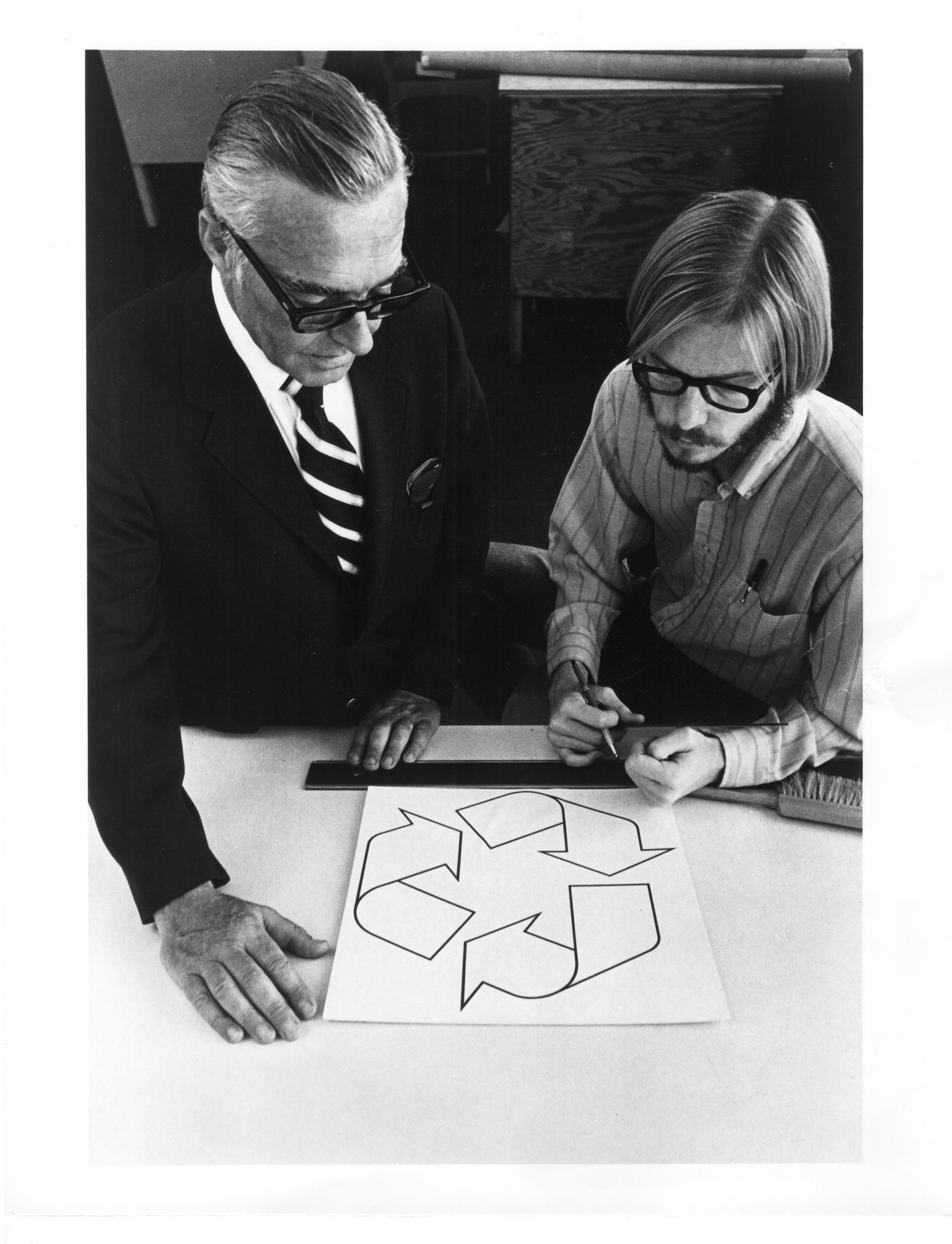

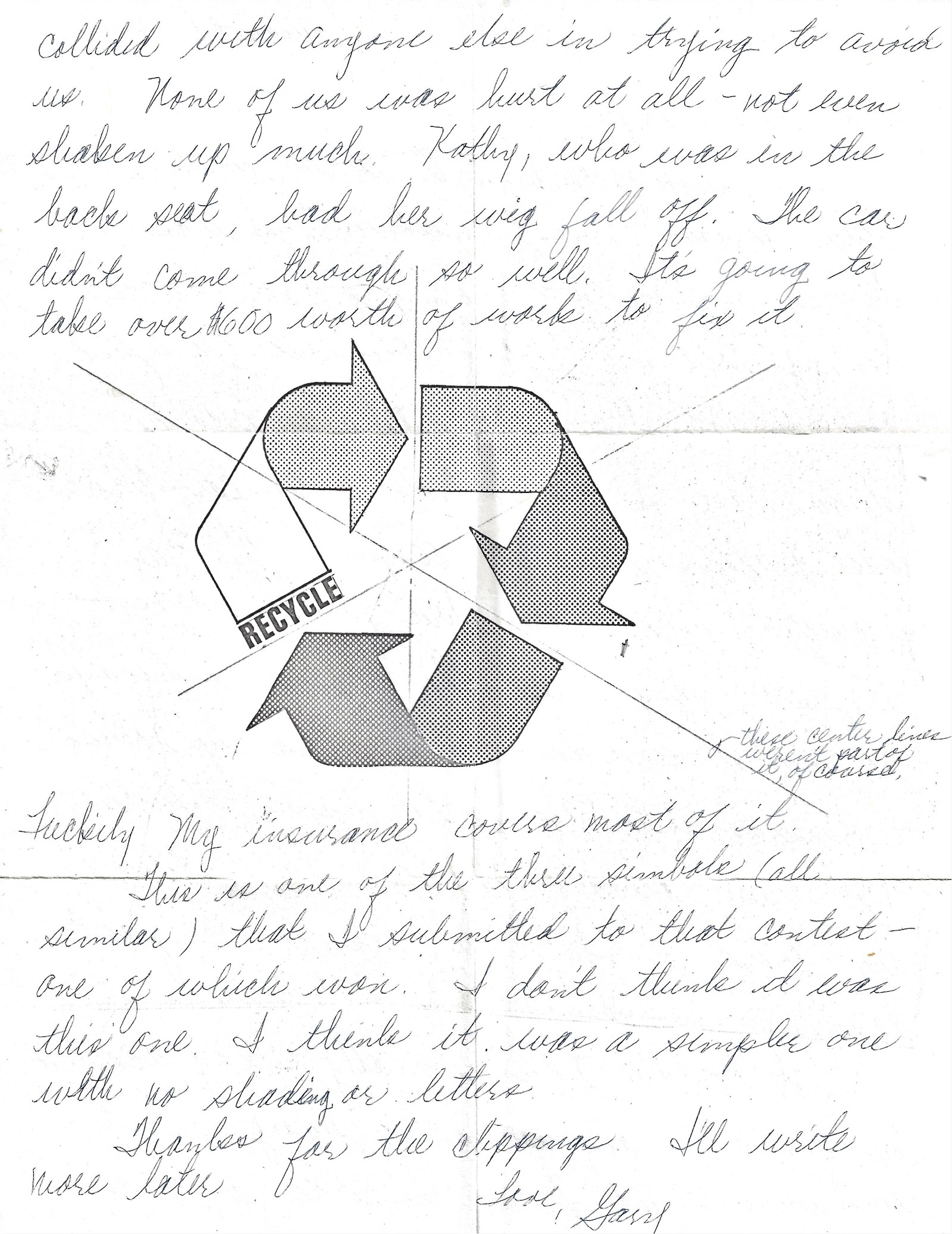

It wasn’t long before the concept acquired its signature symbol. At the time, Gary Anderson was finishing up his master’s degree in architecture at the University of Southern California. He came across a poster advertising a contest to design a symbol for recycling, sponsored by the Container Corporation of America, a maker of cardboard boxes. Inspired by M.C. Escher’s Möbius strip, Anderson spent just a couple of days coming up with designs using the now-famous trio of folded, rotating arrows. The simplest of his designs won, and Anderson was awarded a $2,500 scholarship in 1970. The Container Corporation quickly put the logo in the public domain, hoping it would be adopted on all recycled or recyclable products in order to “spread awareness among concerned citizens.”

The Möbius loop he created soon passed from his mind. “I just didn’t really think of the symbol that much,” he recalls. “It wasn’t used very much in the first couple of years.” One day several years later, however, Anderson was wandering through the streets of Amsterdam in the haze of jet lag when he came across a row of oversized bins emblazoned with a beach ball-sized version of his logo. The Netherlands, purportedly, was the first country to launch a nationwide recycling program in 1972. “It just really shocked me into a realization that there must be something about this symbol,” he said.

Refashioning old materials into new things is a longstanding American tradition. Paul Revere, folk hero of the American Revolution, collected scrap metal and turned it into horseshoes. In the 19th century, used rags were turned into paper, and families stitched together scraps of fabric to create quilts. The desperation of the Great Depression taught people to make underwear out of cotton flour sacks, and the propaganda posters of World War II positioned recycling as a patriotic duty: “Prepare your tin cans for war.”

“It was not in our DNA to be this wasteful,” said Jackie Nuñez, the advocacy program manager at the Plastic Pollution Coalition, a communications nonprofit. “We had to be trained, we had to be marketed to, to be wasteful like this.”

One of the first lessons of “throwaway society” came in the 1920s, when White Castle became the first fast-food restaurant to sell its burgers in single-use bags, advertising them as clean and convenient. “Buy ’em by the sack,” the slogan went. In 1935, the big breweries that survived the Prohibition era started shipping beer in lighter, cheaper-to-transport steel cans instead of returnable glass bottles. Coca-Cola and other soda companies eventually followed suit.

All those paper sacks and cans soon littered the sides of American roadways, and people started calling on the companies that created the waste to clean it up. Corporations responded by creating the first anti-litter organization, Keep America Beautiful, founded in 1953 by the American Can Company and the Owens-Illinois Glass Company. Keep America Beautiful’s advertisements in the 1960s looked like public service announcements, but they subtly shifted the blame for all the garbage to individuals. Some featured “Susan Spotless,” a girl in a white dress who would wag her finger at anyone who soiled public spaces with their litter.

The pressure on American businesses didn’t go away, though. On the Sunday after Earth Day in April 1970, some 1,500 protesters showed up at Coca-Cola’s headquarters in Atlanta to dump hundreds of cans and glass bottles at its entrance. Two years later, Oregon passed the country’s first “bottle bill” requiring a 5-cent deposit on bottles and cans sold in the state, incentivizing people to return them, while Congress was considering banning single-use beverage containers altogether. Manufacturers successfully lobbied against a federal ban, arguing that jobs would be lost, as the historian Bartow J. Elmore recounts in the book Citizen Coke: The Making of Coca-Cola Capitalism. But corporations still wanted to relieve the public pressure on them and outsource the costs of dealing with the waste they were creating. Luckily for them, recycling was in vogue.

In New York City, the war on waste was spearheaded by the Environmental Action Coalition, an organization raising funds for its “Trash Is Cash” community recycling program, with the long-term goal of getting recyclables picked up by city workers outside homes. Curbside recycling seemed to serve everyone’s interest: Environmentalists wanted to waste less, and companies could use it as an opportunity to shift the cost of dealing with waste onto city governments. Businessmen who volunteered with the Environmental Action Coalition solicited millions in donations from their colleagues in the 1970s, writing that recycling had “substantial promise” to fend off any legislation to ban or tax single-use containers.

The campaign was a deliberate attempt to divert attention from more meaningful solutions like bottle bills, yet environmental groups embraced it, according to Recycling Reconsidered, a 2012 book by Samantha MacBride, who worked in New York City’s sanitation department for two decades. The New York City Council started its mandatory curbside pickup program in the late 1980s, several years after the first one began in Woodbury, New Jersey, requiring residents to set out their paper, metal, glass, and some types of plastic in bins at the curb. The idea picked up in cities across the country, with the number of curbside programs growing from 1,000 to 5,000 between 1988 and 1992, spreading the chasing arrows along with them.

“It was in the late ’80s and early ’90s that this thing just becomes everywhere,” said Finis Dunaway, a professor of history at Trent University in Canada. America was running out of places to put its trash, a dilemma captured by the story of a nomadic garbage barge in 1987. In March of that year, a barge teeming with 6 million pounds of trash left Long Island, New York, looking to unload its freight where the landfills weren’t already full. States from North Carolina to Louisiana turned it away, and the barge spent months traveling around the Atlantic coast — all the way to Mexico, Belize, and the Bahamas — looking for a place to dispose of the garbage.

In October, the barge made its way back to Brooklyn, where a court ordered that its contents be incinerated — but not before Greenpeace activists hung a giant banner on the boat: “NEXT TIME … TRY RECYCLING.” Annie Leonard, the former executive director of Greenpeace, told PBS Frontline in 2020 that she wonders whether that banner was a mistake. “I think we were overly optimistic about the potential of recycling,” she said, “and perpetuating that narrative led us astray.”

There’s an iconic scene in the 1967 movie The Graduate, in which Dustin Hoffman’s character, Benjamin Braddock, gets cornered at his college graduation party by one of his parents’ friends. “I just want to say one word to you, just one word: plastics,” the older man says. “There’s a great future in plastics. Think about it.” One generation’s earnest advice for a successful career clashed with a new, skeptical attitude toward plastic, which had already become a byword for “fake.”

By the early 1970s, scientists had learned that whales, turtles, and other marine life were getting tangled up in plastic debris, a problem that was killing 40,000 seals a year. They knew, too, that small plastic fragments were making their way into the ocean, and that plastic residues had entered people’s bloodstreams, presenting what an official from President Richard Nixon’s Council of Environmental Quality deemed a significant health threat, “potentially our next bad one.” The more people learned, the more plastic’s reputation transformed from all-purpose, indestructible wonder into something that maybe shouldn’t be trusted in your new microwave. Between 1988 and 1989, the percentage of Americans who believed plastic was damaging the environment rose from 56 to 72 percent. Larry Thomas, the president of the Society of Plastics Industry, warned in an internal memo that companies were starting to lose business, writing, “We are approaching a point of no return.”

Beverage companies and the oil industry hoped to advertise their way out of the PR problem, laying out plans to spend $50 million a year to tout the polymer’s virtues with slogans like “plastics make it possible.” They also turned to recycling. Lewis Freeman, the former vice president of government affairs at the Society of the Plastics Industry, an industry group, told Grist that he has a vivid memory of a colleague coming into his office, saying, “We’ve got to do something to help the recyclers.”

Freeman tasked the Plastic Bottle Institute — made up of oil giants like BP and Exxon, chemical companies, and can manufacturers — with figuring out how to clarify to recycling sorters what kind of plastic was what. In 1988, they came up with the plastic resin code, the numbering system from 1 to 7 that’s still in place.

Polyethylene terephthalate, or PET (1), is used to make soft drink bottles; high-density polyethylene (2) is used for milk jugs; polyvinyl chloride (3) is used for PVC pipes in plumbing, and so on all through 7, the catch-all category for acrylic, polycarbonate, fiberglass, and other plastics. The Plastic Bottle Institute surrounded these numbers with the chasing arrows logo, giving the public the impression that they could throw all kinds of plastics into recycling bins, whether there was infrastructure to process them or not. The Connecticut Department of Environmental Conservation warned that the confusion it would cause “will have a severe impact on the already marginal economic feasibility of recycling plastics as well as on recycling programs as a whole.”

Once the symbol was operational, Freeman said, “then everybody started putting it on everything.” Companies worked to make it official: Starting in 1989, the Plastic Bottle Institute lobbied for state laws mandating that the code numbers appear on plastic products. Their express purpose was to fend off anti-plastic legislation, according to documents uncovered by the Center for Climate Integrity. The laws eventually passed in 39 states.

By the mid-1990s, the campaign to “educate” the public about plastic recycling had succeeded: Americans had a more favorable opinion of plastic, and efforts to ban or restrict production had died down. But recycling rates — the share of materials that actually get reprocessed — had barely improved. Instead, the United States started exporting plastic waste to China, where turning old plastic into new materials helped meet growing demand from manufacturers. Polling conducted for the American Plastics Council in 1997 showed that people who worked in waste management were losing hope that plastics could be recycled, while the public, journalists, and government officials believed they could be recycled at unrealistically high rates.

The problem was, fulfilling what companies called the “the urgent need to recycle” wasn’t as easy as the advertisements made it look. For decades, industry insiders expressed serious doubts that recycling plastic would ever be profitable, with one calling the economic case “virtually hopeless” in 1969. There are thousands of plastic products, and they all need to be sorted and put through different processes to be turned into something new. The way packaging is molded — blown, extruded, or stamped — means that even the same types of plastic can have their own melting points. A PET bottle can’t be recycled with the clear PET packaging that encases berries. A clear PET bottle can’t be recycled with a green one.

The plastics that do happen to get sorted and processed can only be “downcycled,” since melting them degrades their quality. Recycled plastic, it turns out, is more toxic than virgin plastic, liable to leach dangerous chemicals, so it can’t safely be turned into food-grade packaging. It’s also more expensive to produce. The result of this morass is that there is virtually no market for recycled plastics beyond those marked with 1s and 2s; the rest are incinerated or sent to landfills. Only 9 percent of the plastics ever produced have gone on to be recycled.

As plastic waste piled up and public frustration mounted, the Sustainable Packaging Coalition — backed by corporate giants including Procter and Gamble, Coca-Cola, and Exxon Mobil — launched a bigger, more specific recycling initiative in 2008 called “How2Recycle.” It came with new labels that appeared to provide clarity about which elements of a product could be recycled, distinguishing between plastic wrap and coated trays, sometimes qualifying the recycling logo with “store drop-off” labels for plastic bags and film.

But environmental advocates say that the How2Recycle labels, used by more than a third of the companies that package consumer goods, may be even more misleading than the resin code. For example, plastic yogurt containers made of polypropylene, number 5s, are considered “widely recyclable” under the system, yet only 3 percent of all the polypropylene containers produced actually get recycled.

The plastic resin code with the chasing arrows certainly confused people — 68 percent of Americans surveyed in 2019 said they thought anything labeled with the code could be recycled. But the How2Recycle labels “put the lies on steroids,” said Jan Dell, the founder of the nonprofit The Last Beach Cleanup. It’s not just a tiny triangular indent on the bottom of a container anymore, but a large, high-contrast recycling logo that “stares you in the face.”

Given the dismal state of plastic recycling, it might seem like the best thing to do is throw the chasing arrows in the garbage. But not all recycling is a failure. “Metals are the true success story,” said Carl Zimring, a waste historian at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. As much as three-quarters of all the aluminum that’s ever been produced is still in use, he said. Paper is also relatively easy to process, with more than two-thirds making its way into new products in the U.S. Even for a recycling standby like glass, though, less than a third gets broken down into fragments for new jars and bottles.

The recycling logo still gives anything it touches — whether feasible to recycle or not — a green aura. Surveys show that a majority of Americans believe recycling is one of the most effective ways they can fight climate change, when experts say it’s unlikely to make much of a difference in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. That’s a credit to the iconic triangle, which has had 50 years to entrench itself in our culture. “It’s easy to bash on the image, or bash on corporations, without seeing this as something that is very powerful,” said Dunaway, the environmental historian. So is there a way to give the recycling symbol meaning again?

When recycling started taking off in the early 1990s, there was no definitive, agreed-upon definition of what it meant. “Anything is recyclable, at least theoretically,” one lawyer pointed out in a legal journal in 1991. The effort to impose some sort of order came from California, often the national laboratory for environmental protection. The state passed the country’s first restrictions on green claims in 1990, prohibiting advertisers from using terms like “ozone-friendly” and “recyclable” on items that didn’t meet its standards (though that stipulation didn’t survive a challenge in court).

Wider efforts to restrict the symbol, however, lacked strength and enforcement. In 1992, the Federal Trade Commission told advertisers they could call a product “recyclable” even if only 1 percent of their product was recycled. Not much else happened on that front until 2013, when the group that administers the plastic resin code, ASTM International, announced that it was replacing the chasing arrows with a solid triangle to reduce public confusion. It didn’t require manufacturers to rework their labels, though.

Today, that might finally be changing. When China banned the import of most plastics in 2018, it revealed problems that had long remained hidden. The United States had been shipping 70 percent of its plastic waste to China — 1.2 billion pounds in 2017 alone. States set about finding ways to fix the recycling system, with some focusing on the confusion generated by the symbol itself. In 2021, California — the world’s fifth-largest economy — passed a “truth in labeling” law prohibiting the use of the chasing arrows on items that are rarely recycled. To pass the test, 60 percent of Californians need to have access to a processing center that sorts a given material; on top of that, 60 percent of processors have to have access to a facility that will remanufacture the material into something else.

Though the bill faced opposition from companies right until it passed, the idea resonated with legislators, said Nick Lapis, the director of advocacy at Californians Against Waste. “It was pretty easy to understand that putting the chasing arrows symbol on a product that is not ever going to get recycled is not fair to consumers. Like, it just made so much intuitive sense that I think it kind of went beyond the lobbyist politics of Sacramento.”

Across the country, public officials in New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Illinois, Minnesota, and Washington state are considering similar legislation. This spring, Maine passed a law to incentivize companies to use accurate recycling labels on their packaging. New rules around the recycling logo are also brewing at the national level. Last April, Jennie Romer, the EPA’s deputy assistant administrator for pollution prevention, called for the FTC to put an end to the “deceptive” use of the iconic chasing arrows on plastics in its upcoming revisions to the Green Guides for environmental marketing claims. “There’s a big opportunity for the Federal Trade Commission to make those updates to really set a high bar for what can be marketed as recyclable,” Romer told Grist. “Because that symbol, or marketing something as recyclable, is very valuable.”

Once California’s law goes into effect next year, state laws will clash with each other, since many states still require the resin numbers on plastic packaging. “The question on everyone’s mind is, who’s going to win out?” said Allaway, the Oregon official.

Talk of truth-in-labeling legislation has coincided with another trend — states trying to turn the costs for dealing with waste back on the manufacturers that produced it. Laws requiring “extended producer responsibility,” or EPR, for packaging have already been approved in Maine, Oregon, California, and Colorado. It’s already led to problems in California, since the EPR bill refers to the state’s truth-in-labeling law to determine which materials can be recycled, creating incentives for everything to be labeled as recyclable, Dell said.

Even if the Federal Trade Commission updates the Green Guides to prohibit the deceptive use of the recycling symbol, it doesn’t change the fact that the guides are just suggestions. They don’t carry the weight of law. “The FTC itself has never enforced a false recyclable label, ever, ever, on plastics, not once,” Dell said. One of Dell’s favorite metaphors: “It’s the wild, wild West of product claims and labeling, with no sheriff in town.”

So Dell has appointed herself de facto sheriff, suing companies over their false claims. In 2021, her organization reached a settlement with TerraCycle, Coca-Cola, Procter & Gamble, and six other companies that agreed to change labels on their products. Dell recently filed a shareholder proposal with Kraft Heinz in an attempt to force it to remove recyclability claims from marshmallow bags and mac-and-cheese bowls destined for the landfill.

Another promising legal push is coming from California Attorney General Rob Bonta, who has been investigating fossil fuel and chemical companies for what he called “an aggressive campaign to deceive the public, perpetuating a myth that recycling can solve the plastics crisis.” Despite mounting awareness of plastic’s threat to public health, oil and chemical companies around the world make 400 million metric tons of the polymer every year, and production is on track to triple by 2060. It’s the oil industry’s backup business plan in the expectation that wealthy countries will shift away from gasoline in an effort to tackle climate change, since petroleum is the basic building block of plastics. Exxon Mobil, the world’s third-largest oil producer, ranks as the top plastic polymer producer.

Stricter enforcement around the use of the chasing arrows could lead to more accurate labels, less public confusion, and better outcomes for recycling centers. But it’s worth asking whether more recycling should even be the goal, rather than solutions that are much better for the environment, like reducing, reusing, refilling, and repairing. As Anderson, the symbol’s inventor, says, “I don’t think it’s really fair to blame a graphic symbol for all of our lack of initiative in trying to do better.”

Correction: This story originally mischaracterized Samantha MacBride’s position.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How the recycling symbol lost its meaning on Jun 12, 2024.