This story was originally published by Capital B.

At the edge of Saginaw Street, a hand-painted sign is etched into a deserted storefront. “Please help, God. Clean-up Flint.”

Behind it, the block tells the story of a city 10 years removed from the start of one of the nation’s largest environmental crises.

Empty lot. Charred two-story home. Empty lot. Abandoned house with the message “All Copper GONE,” across boarded-up windows.

John Ishmael Taylor, 44, was born in this ZIP code, 48503, and he’s seen firsthand the neglect of the place he loves, one he hopes will be reborn for his young children.

“The water crisis, no more jobs, the violence,” Taylor said, has left Flint like a “ghost town — a ghost town with a whole bunch of people still here.”

Over the past decade, Flint’s water crisis has revealed how government failures at every level could effectively kill a city while opening the country’s eyes to how an environmental crisis could wreak havoc on all facets of life, make people sick, destroy a public school system, and kill jobs.

Four years after Flint residents reached the largest civil settlement agreement in Michigan history, Taylor and tens of thousands of other victims still haven’t received a penny from the $626.25 million pot. The only money doled out has gone to lawyers involved in the case, not those who’ve been haunted by the crisis’s true impacts. Still, even when residents ultimately receive the funding, most expressed doubts that the payouts will have any true benefits for their life.

Adam Mahoney / Capital B

In many ways, Taylor’s life shows the violent and widespread nature of America’s water crisis. After being born in Flint, he’d spent his preteen years living outside Jackson, Mississippi, where brown water has flowed through Black homes for decades.

Taylor, a single father, moved back to Flint permanently in January 2014. Within a year, lead levels in the drinking water of three of every four homes in his ZIP code were well above federal standards.

His youngest son, Jalen, was born 52 days before the start of the water crisis, which is recognized as April 25, 2014, the day the city infamously switched its water source from Lake Huron to the Flint River.

The rashes started immediately for baby Jalen, speckling the inside of his legs with coarse, red blotches. Within a few years, he was diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and a form of autism spectrum disorder; both ailments are associated with lead poisoning.

Taylor says he has battled with anxiety in the aftermath as 20 percent of the city’s residents and hundreds of businesses packed up and left. Flint’s unemployment rate is now 1.5 times higher than the national average as 70 percent of children grow up in poverty.

He wonders what that means for his children.

“I always wonder how they’re gonna do because this is a long-term effect — we’re talking about lead poisoning. This is going to be with them for most of their life. It’s depressing,” he said, and he’s felt no restitution. He believes it has led to a citywide mental health crisis. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1 out of 5 Flint residents reported having poor mental health, which is nearly 40 percent higher than the U.S. average.

Adam Mahoney / Capital B

Angela Welch, who has lived in Flint for four decades, understands the health implications intimately. She recently tested for lead levels in her blood at 6.5 micrograms per deciliter. Anything above 5 micrograms is considered extremely dangerous for your health.

Since the start of the crisis, Welch has developed chronic skin and cardiac issues, had multiple surgeries, and lost part of her leg to amputation. Her brother Mac showed Capital B the scars along his body from water-induced rashes.

Welch questions what repair looks like for her family. “We gotta be dead to get our money? They want us dead to receive anything from the crisis.”

The federal Environmental Protection Agency and officials with Flint’s mayor’s and city attorney’s offices did not respond to multiple requests from Capital B for comment.

Residents argue that even though they’ve brought the country’s water woes to the forefront, they’re in a worse position today despite hundreds of millions of dollars of investment — and they want you to know that your city can be next.

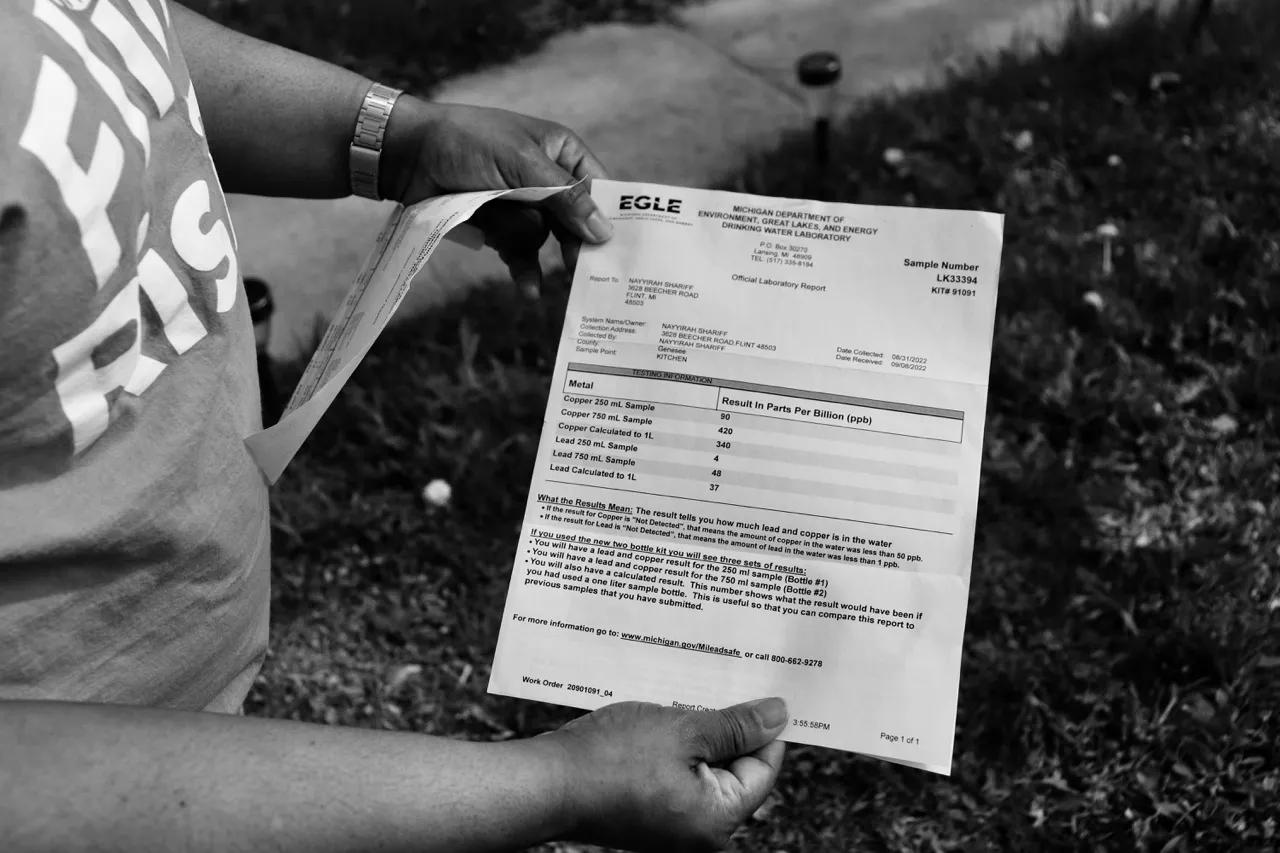

“We’re seeing it happen to Jackson,” said Nayyirah Shariff, a community activist, whose water is still testing for lead at levels three times higher than federal limits.

“It’s like they have the same playbook to decimate a city.”

What Flint tells us about the nation’s water crises

Flint opened the nation’s eyes to a brewing water affordability and infrastructure crisis, ultimately leading to billions of dollars invested in cleaning the country’s drinking water, improving water plants and roads, and building climate resilience.

There are roughly 9 million lead pipes in service across the U.S., and they’re everywhere, from the oldest cities across Massachusetts to Florida, which leads the country in lead pipes but where infrastructure and the average home is among the nation’s youngest. In November, the Biden administration outlined a plan to replace all 9 million within the next decade, making 50 percent of the $30 billion price tag available from the federal government.

Yet Flint residents and experts told Capital B that the main flaws of the federal government’s plan have been realized in the city over the past decade: It is complicated, time-consuming, and costly to identify and replace water lines. Not to mention, as Shariff explained, replacing lead water lines is not the “magical silver bullet” to eradicate the issue. The lead service line in her home was replaced in 2017, yet her water is still filled with more lead than federal limits allow.

As officials have claimed that the use of water filters and replacement of lead water lines has solved the crisis, including an infamous declaration by former President Barack Obama in 2016, some residents in Flint have felt confused about the true safety of their water.

When approached by Capital B in April, James Johnson explained how a state-conducted test for lead in his drinking water in 2023 returned a clean bill of health. However, public records show Johnson’s property’s lead results were actually 19 parts per billion. The federal limit is 15.

“I don’t know what to think [about the water,]” Johnson said after Capital B explained the results. “We just use filters. We have been since ’14, but they said it’s all clean.”

Flint officials did not respond to Capital B’s request for data related to the status of its water line identification and replacement work. This month, a federal judge found the city in contempt of court for missing deadlines for lead water line replacement and related work in the aftermath of the water crisis.

In addition, as the nation focuses on drinking water, lead lines have created another crisis that rarely gets attention: how lead contamination has torn through kitchens and bathrooms. Flint residents told Capital B that since the crisis began, they’ve had corroded toilets fall through floors, and their shower heads turn black from buildup every few months.

“Dirty water doesn’t just impact service lives,” explained Claire McClinton, a Flint resident and former autoworker. “It’s very naive to think that was the only thing that was impacted, and people do not have the money or support to fix these things.”

All the while, Flint has had amongst the most expensive water bills in the country. A 2016 analysis revealed that the average household was paying more than $850 annually for water services, making it the most expensive average bill in the country. Today, the average bill is $1,200 annually.

McClinton is afraid that as the country chugs on with its focus on drinking water, Black communities will be harmed by efforts to cut costs, or worse, boxed out of their access to publicly run water systems. More than 20 percent of Americans now rely on private companies for drinking water, a substantial increase compared to 2019, according to the National Association of Water Companies. On average, private water utilities charge families 59 percent more on their water bills than public utilities.

“We don’t want corporations to benefit from all this spending — we should want to keep our water public,” McClinton said.

Still, public water systems have their challenges supporting Black communities as well. Failing public water systems are 40 percent more likely to serve people of color, and they take longer than systems in white communities to come back into compliance. Funding to reach these communities remains faulty despite the Biden administration’s goal of spending 40 percent of funds on “disadvantaged communities.”

A Capital B analysis found that 27 percent of drinking water funds from the bipartisan infrastructure law went to “disadvantaged communities” in 2022, and the two states that received the most funds characterized for “disadvantaged communities” were Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, where less than 10 percent of residents are Black.

McClinton said it’s bittersweet to watch Flint purportedly influence the nation for the better while things remain “broken” for Black communities.

“The system has failed us. We did all the things you’re supposed to do; we participated in water studies, and our water is still dirty, and our health is still bad,” she said. “There’s this thing where they say every generation lives better than the next generation, but all of that is turned upside down right now, and the water crisis is just a manifestation of it.”

‘The start of the second civil war’

In a stream of whiteness, Confederate flags, and Make America Great Again signs, the 60 miles between Detroit and Flint tell the story of Black life in Michigan, Welch said. “Because we are a majority here and have conquered [Flint and Detroit], they want to get back at us,” she said.

Over the past decade, as Detroit’s financial crisis peaked and Flint’s water crisis began, far-right white-led groups have surged and a white-led militia plotted to abduct the state’s governor.

“It feels like the start of the second civil war,” Welch said, all while Flint is “left behind.”

It’s seeing this shift intensify that has led some residents to see deeper racial undertones in not only Flint’s battle over water affordability and rights, but also the nation’s.

“The power structure is coalescing over water,” McClinton said.

Flint’s issues began primarily because of a plan that was concocted to save the city money during its water-delivery process. Similar situations are happening outside of Chicago in a majority Black and Latino town, and in Baltimore.

Not to mention the glaring similarities between Jackson and Flint, both majority-Black cities where local Black leadership was overridden by white leaders at the federal and state levels. In Jackson, after an EPA lawsuit against the city allowed the federal government to take control of the water, residents are still fighting to be included in the process.

The attack on Black life has also widened the racial gap within the city, Shariff said.

In a commemorative event headlined by a public health researcher from Michigan State University and attended by roughly 50 people the week before the 10-year-anniversary, just five attendees were Black.

It’s events like these, Shariff says, that highlight the disconnect between local leaders, academic researchers, and those directly impacted by the crisis. “All this money these places are spending feels like for nothing,” she said. “People marching in the streets weren’t asking for book talks or community health assessments. We asked for reparations and resources for Black self-determination.”

The crisis is a chronic illness

For some residents, like Taylor, there is still hope that the settlement checks will hit their bank accounts and improve their lives. Children affected by the water crisis are expected to receive 80 percent of the record settlement.

Adam Mahoney / Capital B

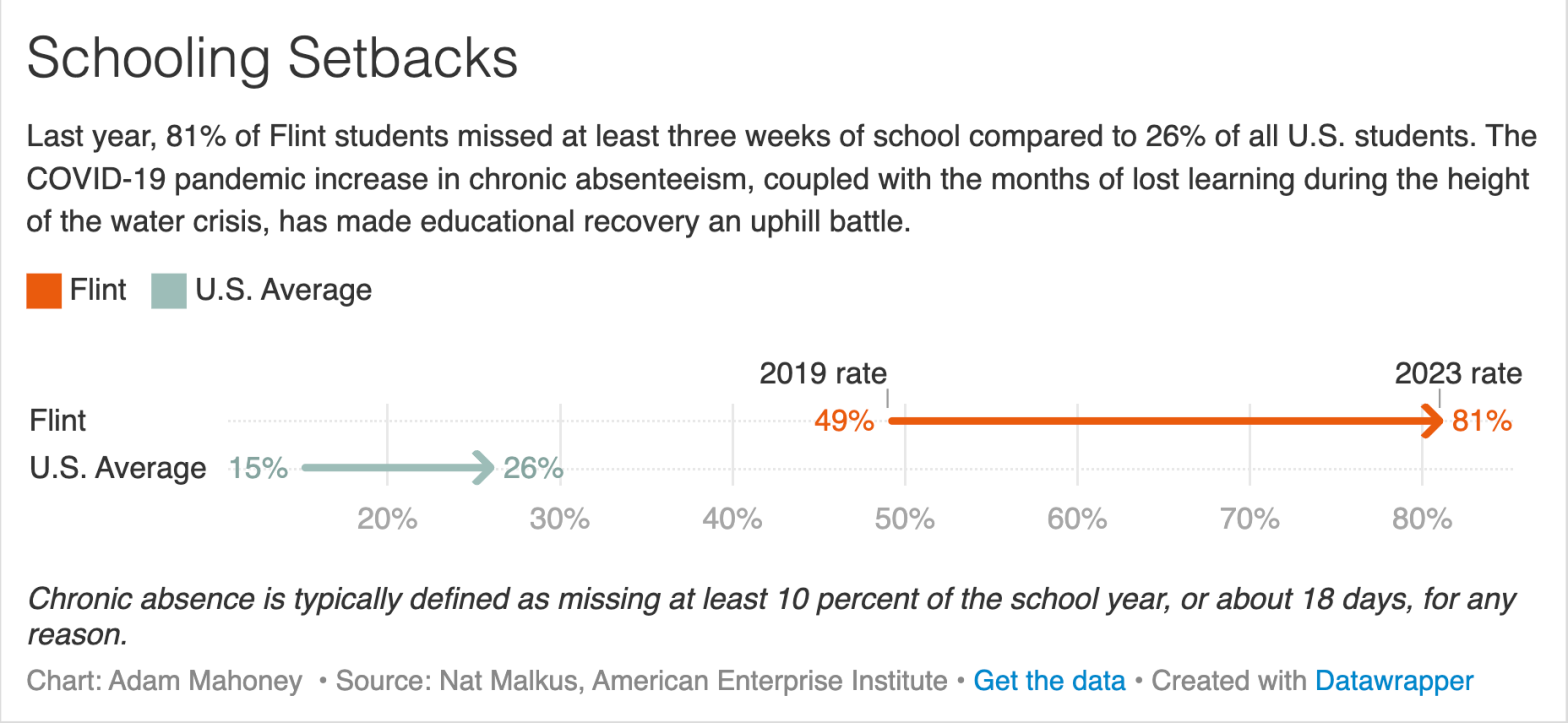

As Flint schools have crumbled in the aftermath of the crises, in addition to experiencing an 8 percent increase in the number of students with special needs, especially among school-age boys, Taylor hopes to use the money to better their educational opportunities and put them through college.

However, for others, including Welch and Shariff, the expected payout of $2,000 to $3,000 for adults feels like a slap in the face. There is also a lot of confusion around the settlement process, with two residents telling Capital B they thought the money was already gone, which stopped them from attempting to be a part of the process.

In a lot of ways, although harder to find, opportunities have reached the city in recent years, including through a guaranteed income program for every pregnant person and infant in the city. The new program “prescribes” a one-time $1,500 payment after 20 weeks of pregnancy, and $500 a month during the infant’s first year.

Yet, it still remains challenging to remain confident in change.

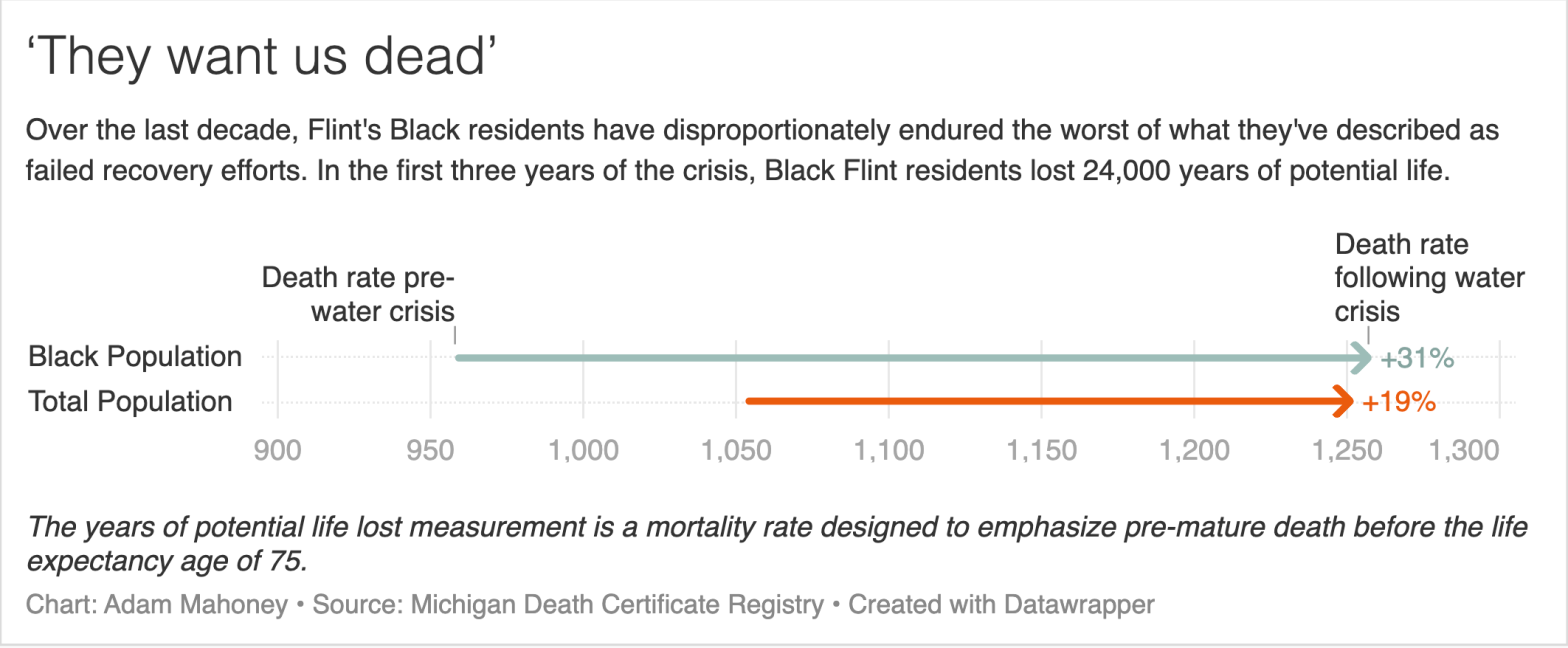

“With all the experiences we’ve had over the 10 years, our hopes have been dashed,” explained McClinton, who every April 25 helps to organize a day of commemoration for Flint residents. As Capital B has reported, the water issues afflicting Black communities are violent in many ways, and it trickles down into increasing situations of despair around housing, mental and physical health, and communal violence. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic widened the racial death gap in Flint, Black residents’ death rate climbed at a rate that was more than twice the city’s death rate between 2014 and 2019, according to Capital B’s analysis of state data.

Several Flint residents explained how the mental health strain caused by the water crisis created a cycle of “disunity” and the inability to trust not just the government or the water flowing out of their pipes, but also the people around them.

“Everyone is just on edge,” Taylor said, “and that has everything to do with the water.”

In the city’s Black areas, it’s hard to find a block without an abandoned home or grassy field full of trash and plastic water bottles. Taylor said it’s depressing to drive through your neighborhood to see your former schools empty, graffitied, and boarded up, or parks closed and desolate.

As job opportunities have become harder to find, so has housing. Nearly all of the dozen residents Capital B spoke to for this story said they experienced housing insecurity at times over the past decade.

Due to a lack of affordable housing options, the average stay at the city’s housing shelter has increased from less than two months to over five. The public housing waitlist has ballooned to two years, even as some public housing buildings still have high levels of lead in the water, including the Richert Manor homes where Welch lived for many years at the height of the water situation.

In the meantime, as race, namely being Black in America, stands as the biggest risk factor for lead poisoning, more so than even poverty or poor housing, Flint residents say their home serves as a warning to other Black communities.

Nationwide, Black children have the highest blood lead levels. As such, even as billions are pumped into fixing the issues, the next generation of Black Americans will remain altered by the impacts of lead poisoning.

As Shariff said: “The water crisis is like having a chronic illness — I mean, it gave me a chronic illness — but it is basically like you’re dealing with it, and it never goes away.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline A decade later, Flint’s water crisis continues on Apr 28, 2024.