Elephants are highly intelligent and social, forming close family groups and showing understanding, cooperation and empathy in their relationships.

Now, an international team of animal behaviorists have confirmed that elephants greet each other with a complex array of gestures and vocal cues, depending on the individuals and circumstances.

“Elephants live in multi-level societies where individuals regularly separate and reunite. Upon reunion, elephants often engage in elaborate greeting rituals, where they use vocalisations and body acts produced with different body parts and of various sensory modalities (e.g., audible, tactile),” the study said.

The researchers — from the Universities of Vienna, Portsmouth and St. Andrews — observed greetings between nine semi-captive African elephants on Zimbabwe’s Jafuta Reserve for a month in 2021, reported Phys.org.

“Greeting is a tricky context because it’s difficult to understand what the gestures mean. They’re more akin to hugs, kisses on the cheek, or hand shakes that we use when we greet each other. But our next steps are to explore gestures in wild elephants in more explicit contexts that can help us understand what they mean,” Vesta Eleuteri, lead author of the study and a PhD student at University of Vienna’s Department of Behavioral and Cognitive Biology, told EcoWatch in an email.

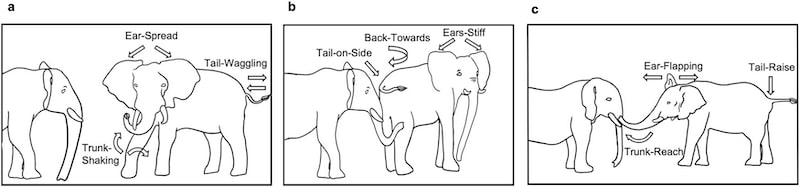

Illustrations of frequent body act types used by semi-captive African savannah elephants during greeting. Drawn by Megan Pacifici

Previous research revealed that elephants’ extreme intelligence is comparable to that of dolphins and chimpanzees. Their matriarchal social structures are also complex.

“Elephants show advanced intelligence to the extent of non-human apes. They are well known for their long-term memory, remembering paths to resources located km away for years. They have sophisticated discrimination skills — for example, they can distinguish humans of different ethnicities based on how they speak or smell. And elephants are known for their empathetic behaviour towards each other, often helping individuals in need. Elephants live in a multi-level society where individuals form different types and degrees of relationship with one another,” Eleuteri told EcoWatch.

Elephants pay attention to details of perception, such as whether others are looking their way. Most were more apt to make gestures if another elephant was watching, and they used loud ear-flapping to get their attention if they weren’t.

“Elephants were more likely to use visual gestures (such as ear-spreading, trunk-reaching, or trunk-swinging) when their partner was watching,” Eleuteri said, according to a press release from University of St. Andrews, “but used acoustic gestures (such as ear-flapping) or touched their partner when not being watched. This suggests they are able to take into account the other elephant’s visual attention when gesturing.”

Eleuteri said these targeted behaviors indicated they were tailored to their specific audience.

“In terms of their cognition, finding that elephants target gestures to their audience depending on whether the audience is looking at them, our study suggests that they might be able to take into account the visual perspective of others,” Eleuteri told EcoWatch.

The researchers found that it was not just female elephants who displayed evidence of close social bonds.

“In terms of their sociality, what was interesting to find is that our male elephants used the same excited and elaborate greeting behaviour used by closely bonded female elephants in the wild. This may be because our semi-captive elephants live in a tight social group, where individuals [are] likely more socially bonded compared to male elephants in the wild, who tend to be more solitary or form loose associations. This means that, like in humans, social relationships change the way elephants greet,” Eleuteri said.

The researchers discovered that elephants find greeting each other important. When two elephants meet who haven’t seen one another in a while, they both engage in behavior that is evidently meaningful. They may swing their trunks or use them to touch each other or flap and spread their ears. Vocalizations tended to be different types of rumbles.

“When we meet a long-term friend we may hug them strongly or kiss them, while when we meet a stranger we usually shake hands. Elephants do the same. In general, as previous research has observed chimpanzees and other apes altering their visual and tactile gestures according to whether they are being looked at and combining vocalisations and gestures in specific ways, these findings are important because they suggest that these communicative abilities have evolved independently in distantly related (and very physically different!) species sharing complex societies and advanced intelligence,” Eleuteri told EcoWatch.

In the new study, the researchers focused on greetings to find out whether elephants have additional ways to communicate that had not been previously observed.

“Elephants are known to have a rich repertoire of acoustic, visual, tactile, and chemical signals in their communication, so I was already pretty convinced about the complexity of elephant communication. However, the majority of studies on elephant communication concern their acoustic or chemical/olfactory communication. This may be because elephants are known to extensively heavily rely on hearing, while there is the common belief that elephants don’t rely much on vision,” Eleuteri said.

Eleuteri said earlier studies had shown that elephants do indeed use all of their senses when communicating, including sight and touch.

“Previous researchers like Dr. Joyce Poole had reported elephants using many conspicuous visual or tactile body actions in a variety of different social contexts, strongly suggesting that they do indeed rely a lot on vision or touch for social purposes. So it was nice to find that visual and tactile gestures are an important part of their greetings, that they use them by taking into account their greeting partner’s visual attention, and combine these gestures with calls in specific ways and orders. Elephants were also previously known to combine calls together in specific ways. The ability to combine signals in specific ways and orders is a necessary pre-requisite of syntax, so it might well be that elephants have some form of syntactic abilities in their communication, a realm for future studies!” Eleuteri added.

In the field, the research team observed and recorded 1,014 physical actions of elephants greeting each other, along with 268 vocalizations.

“There were thorough descriptions of wild elephants greeting with many different calls and body actions in an apparently chaotic manner, thus finding that they actually combine calls and body actions in specific ways and with some ordered structure was novel,” Eleuteri told EcoWatch. “We also found that elephants greet by appropriately targeting visual, acoustic, and tactile gestures at their audience depending on the audience´s state of visual attention (for example, if we’re in a noisy bar and I want to tell you ‘let’s leave’ and you are looking at me, I might use a visual gesture, but if you are not I might touch you). The ability to target visual gestures was previously shown from captive elephants towards a human. So finding this capacity between elephants, although quite expected for people who know elephants, was also novel.”

Elephants provide many ecosystem services and are essential to the habitats in which they live.

“Elephants are not just clever giants — they are a keynote species playing a crucial role in the environment they live in. They are known as the gardeners and architects of their habitats due to their massive ecological impact,” Eleuteri said.

Elephants face many threats that have caused their numbers to dwindle in the past century.

“It is estimated that, at the turn of the 20th century, 10 million African elephants roamed the African continent. Today, around 400 thousand elephants are left in Africa,” Eleuteri told EcoWatch. “Two of the major threats for wild elephants are poaching for ivory and habitat loss, the reduction of available space for elephants due to human expansion, which leads elephants to live in fragmented landscapes and engage in negative interactions with local communities.”

Despite their threatened status, Eleuteri remains hopeful for the future of these highly intelligent, empathetic and social guardians of the forest.

“Despite the dire situation, I still have hope that elephants will manage to survive and there are amazing people working hard for elephants and their future. There are a few places, like Botswana or Zimbabwe, where today their number is stable and, if left in peace, elephants have a nice growth rate,” Eleuteri said. “I think what people can do is avoid buying ivory to help decrease the interest in it and donate to elephant conservation organisations. More adventurous people can maybe join some volunteering programs to help them first-hand about (and experience how amazing they are!). In general, I think it’s important to raise awareness on how special, ecologically important, and how threatened elephants are to reach a wider group of people who can help them directly or indirectly.”

The study, “Multimodal communication and audience directedness in the greeting behaviour of semi-captive African savannah elephants,” was published in the journal Communications Biology.

The post Elephants Greet Each Other With ‘Elaborate’ Combinations of Vocal Cues and Gestures, Study Finds appeared first on EcoWatch.