Quick Key Facts

- Global species populations have declined by an average of 69% since 1970.

- The Endangered Species Act was enacted by the U.S. Congress in 1973 and has saved 99% of the species it protects from extinction.

- At least one-third of plants and animals in the U.S. are threatened with extinction.

- Habitat loss, low genetic variation and other human impacts like pollution, wildlife trafficking, agriculture and development, and climate change are major drivers of endangerment and extinction.

- The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) maintains the international “Red List” of endangered and threatened species.

- Scientists warn that the loss of plant and animal species due to climate change could cause an “extinction domino effect.”

The Endangered Species Act

To understand what “endangered species” means, it’s important to unpack the Endangered Species Act (ESA), which followed the Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966, the first piece of federal endangered species legislation. Enacted by the U.S. Congress in 1973, the ESA states that the federal government has a responsibility to protect endangered and threatened species. They must also protect the areas or regions necessary for the survival of the threatened species, called “critical habitats.”

The ESA set forth definitions of both “endangered” and “threatened” species. As stated in the Act, endangered species are “any species which is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range,” and threatened species are “any species which is likely to become an endangered species within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range.” Species in both categories are called “listed species,” and can become “delisted” if they are no longer endangered or threatened.

It’s important to note that species can be listed as endangered at the state, federal and international level. They are managed under the ESA if they are listed at the federal level, but many states have their own versions of endangered species laws too.

How Are Species Protected Under the Act?

Species listed as threatened or endangered species then get protections by the federal government. They are protected from trade, sale and “take,” which prohibits anyone to “harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill trap, capture, or collect, or to attempt to engage in any such conduct” with these species, as well as interfering with breeding and behavioral activities in their critical habitat.

Three major provisions included in the Endangered Species Act lend it strength:

- Citizen suit provision. Members of the public — whether individuals or public interest groups — can petition to have a species listed as threatened or endangered, ensuring that federal agencies are taking action.

- Critical habitat provision. Agencies must protect the lands and waters that a species needs to survive and recover. When a species is listed, a critical habitat is also designated so a recovery plant can be drawn up.

- Consultation provision. Federal agencies have to avoid doing anything that jeopardizes protected species, including “adversely modifying” their critical habitats.

Ultimately, the ESA has been very successful. By some estimates, it has saved 99% of the species it protects from extinction.

How Do Species Get ‘Listed’ Under the Act?

A status review is conducted by the USFWS and NOAA to determine whether a species warrants protection under the ESA by giving it one of these designations. It’s a lengthy process for a species to get listed. It’s supposed to take only two years, but on average it takes about twelve. “Candidate” species — that is, those petitioning to become listed species — have to qualify for protected status under the ESA based on several factors.

If any of the following five factors are met, a species must be listed as endangered or threatened, according to NOAA:

- Present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of its habitat or range.

- Over-utilization of the species for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes.

- Disease or predation.

- Inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms.

- Other natural or manmade factors affect its continued existence.

Every five years, a review must be conducted of listed species to determine whether the criteria for the recovery plan set forward have been met. Now, more than 1,300 species are protected (or “listed”) as either endangered or threatened under the ESA in the United States.

The ‘Red List’

While the Endangered Species Act focuses on protection at the national level, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) maintains the international “Red List” of endangered and threatened species. The IUCN compiles information on animals, plants and fungi from more than 100 countries and regions, and evaluates their risk of extinction. By their latest count, more than 44,000 species are threatened with extinction worldwide. This includes 41% of all amphibians, 37% of sharks and rays, 36% of reef-building corals, 34% of conifers, 27% of mammals and 13% of birds.

Red List Categories

The Threatened Species list identifies those listed as Critically Endangered (CR), Endangered (EN) or Vulnerable (VU). Evaluations are based on five criteria: population reduction rate, geographic range, population size, population restrictions and probability of extinction. Population reduction is measured over 10 years, or three generations.

Geographic range considers the “area of occupancy” or a species, and the “extent of occurrence” — or the smallest area that could encompass all the sites that the species lives in. Smaller numbers are usually indicative of a threatened population. Lastly, “population restrictions” is a combination of population number and area of occupancy.

Species are categorized by threat level based on the five evaluated criteria, ranging from “least concern” to “extinct”:

- Least concern. There is no concern about population numbers. Human beings, pigeons, houseflies and domesticated cats and dogs would all fall under this category.

- Near threatened. The species might not be currently threatened, but will likely fall under that category in the future.

- Vulnerable species. High risk of becoming extinct in the wild.

- Population reduction rate: 30-50%

- Geographic range: Extent of occurrence is under 20,000 square kilometers, and area of occupancy is under 2,000 square kilometers.

- Population size: Fewer than 10,000 mature animals.

- Population restrictions: Restricted to under 1,000 mature individuals, or area of occupancy is under 20 square kilometers.

- Probability of extinction: 10% within 100 years

- Endangered species. Very high risk of becoming extinct in the wild.

- Population reduction rate: 50-70%

- Geographic range: Extent of occurrence is under 5,000 square kilometers, and area of occupancy is under 500 square kilometers.

- Population size: Fewer than 2,500 mature animals, or if the population has declined by 20% or more within five years or two generations.

- Population restrictions: 150 mature animals

- Probability of extinction: 20% within 20 years or 5 generations

- Critically endangered species. Extremely high risk of becoming extinct in the wild.

- Population reduction rate: 80-90%

- Geographic range: Extent of occurrence is under 100 square kilometers, area of occupancy is under 10 square kilometers.

- Population size: Fewer than 250 mature animals, or if population has declined by 25% or more within three years or one generation.

- Population restrictions: 50 mature animals

- Probability of extinction: 50% within 10 years or 3 generations

- Extinct in the wild. Includes plants that only survive in cultivation, or animals only in captivity. The term also encompasses species that are only surviving outside of their historic range.

- Extinct. There are no known individuals of the species remaining.

How Do Species Become Endangered?

Take the passenger pigeon, for example. These birds used to fly by the thousands overhead in North America but not a single passenger pigeon remains. The cause of their extinction is twofold: many were shot by humans for sport and food, and their forest habitat was cut down to build cities and plant farmland in a rapidly expanding America. They are a prime example of how human intervention can damage a species to the point of extinction — even one that once comprised 25-40% of the total bird population in the United States.

A passenger pigeon stamp on a National Wildlife Federation stamp sheet in 1966. Kevin Dooley / Flickr / CC BY 2.0

Loss of Habitat

Extinction and endangerment can also happen, however, outside of human intervention. Glaciers melt after an ice age, pushing out plants and animals that can’t adapt to new conditions. A volcano can erupt and kill off an entire species. Think of the dinosaurs, who lost their habitat during the Cretaceous period when an asteroid struck the Earth. The debris sent into the atmosphere prevented light and heat from reaching the ground, and the dinosaurs were unable to adapt to this different climate. Their populations became endangered, and eventually extinct.

Increasingly, however, human activity is the reason for habitat loss. We clear enormous amounts of space for housing, agriculture and industry, leaving it inhospitable to the creatures who once lived there. When huge swaths of rainforest in South America are razed (or “deforested”) to create grazing space for cattle, the entire habitat that a species depended on is destroyed, contributing to decreases in their population. Such destruction has indirect impacts as well — while a species might not have been directly impacted by this loss, they might have depended on another impacted species as a food source, now leaving them without the necessary resources to survive.

Loss of Genetic Variation

Genetic variations allow species to adapt to changes in their environment. Without variation, species don’t develop resistance to disease or other threats, putting them at greater risk of extinction. Inbreeding prevents new genetic information from entering the gene pool, so disease is much more common and deadly within the group. Cheetahs, for instance, went through a period of inbreeding during the last ice age, so they don’t have as much genetic variation. As a result, fewer cheetahs survive to maturity than other species. Human causes like overfishing/overhunting can reduce the number of mature individuals that can breed, contributing to inbreeding.

A cheetah at Maasai Mara National Reserve in Kenya. Ray in Manila / Flickr / CC BY 2.0

Other Human Impacts

Extinctions have historically occurred during the five mass extinction events throughout the planet’s history, which were largely the result of natural causes. However, extinction is now occurring at a rate 1,000-10,000 times faster due to humans. Through travel and trade, humans introduce new diseases to species by spreading pathogens to new locations, and also introduce non-native species to areas where they are not meant to live, therefore altering food chains and possibly pushing out other native species. As we encroach upon the habitat of wild animals, species are at greater risk of death by car collisions and hunting too.

Pollution and Toxicity

Toxins released into the environment by humans, including pesticides, can contribute to the threatened status of species. Bald eagles were heavily impacted by DDT, which was used on farms as an insecticide and then washed into waterways where it poisoned fish. After eagles ate the poisoned fish, they began laying eggs with thin, fragile shells that cracked before the babies could hatch. Since DDT was banned in 1972, bald eagle populations have bounced back.

The introduction of trash and plastic into ecosystems by humans — especially in our oceans — can also harm species. It’s estimated that 100 million ocean animals are killed as a direct result of plastic each year.

Wildlife Trafficking and Removal From Habitats

Wildlife trafficking involves the illegal trade, smuggling, poaching, capture or collection of wildlife that’s protected, endangered or managed. It’s the second biggest direct threat to species, following only habitat destruction. The IUCN found that 958 species are at risk of extinction due to international trade. African elephants, for one, are heavily trafficked for their ivory tusks to make products like jewelry and chess sets. Consequently, fewer than 420,000 of these elephants remain of the 1.2 million that once lived in 1980.

Climate Change

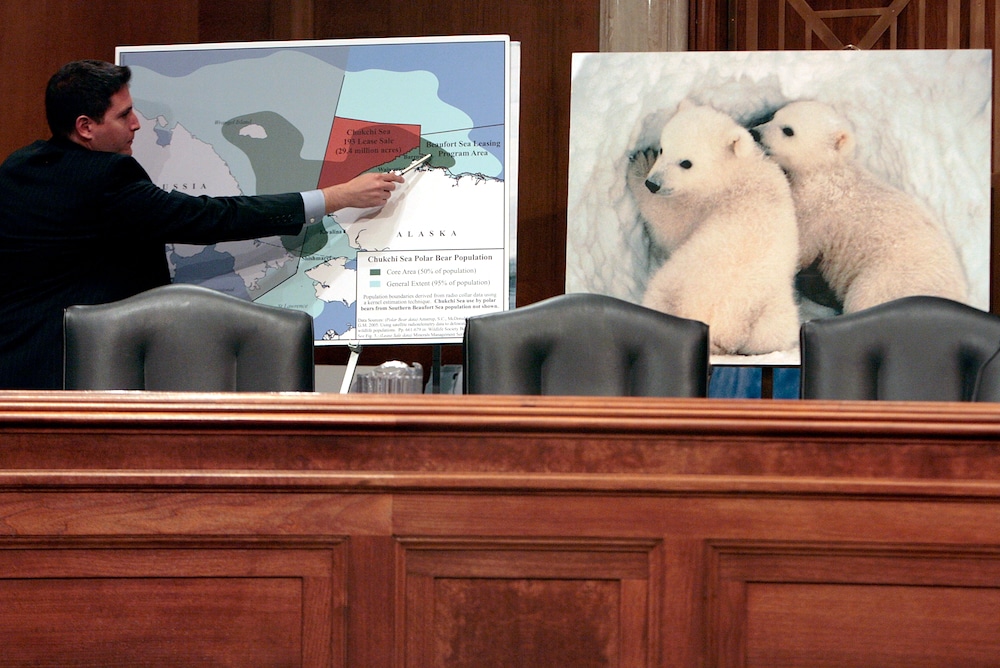

Given the expansiveness of climate change and its impact, it’s no surprise that it’s a major threat to biodiversity. By 2050, some biologists estimate that 25% of plants and animals will be extinct in the wild as a result of climate change. Warmer temperatures are altering habitats and leaving species without places to breed and find food, disrupting seasonal cues for migratory animals, and causing sea level rise to damage coastal ecosystems, among many other impacts. In 2010, phytoplankton populations had dropped 40% since their 1950 levels, and rising sea surface temperatures were identified as the cause. Losing this key species that consumes carbon dioxide and produces oxygen during photosynthesis would be devastating to ocean health.

What Are the Most Endangered Species on Earth?

Animals

Amur Leopard

Only about 100 amur leopards are left in the wild, surviving only in the far east of Russia and northeastern China. Although their populations have stabilized — rising from 30 individuals in the 1970s to roughly 100 now — they have been considered “critically endangered” since 1996. They are primarily threatened by poaching for their spotted fur, habitat loss and lack of prey. Their prey base isn’t sufficient to sustain big populations, and so to help the leopards, local deer and hare species need to be protected from hunting as well.

African Forest Elephant

Once listed together with African savanna elephants, African forest elephants are now considered separately. These critically endangered elephants are found in thirty-seven countries in sub-Saharan Africa, and are mainly threatened by poaching and habitat loss to agricultural development. Their ivory tusks are highly valuable, and are a main reason why these elephants are poached. However, even if poaching stopped now, it would take a long time for populations to recover, since elephants reproduce slowly. Between 1928 and 2021, their populations declined more than 80%. Now, only 415,000 individuals exist in the wild in about 25% of their historic range. African forest elephants are important agents of seed dispersal. Many seeds they eat — some too large for other animals to ingest — remain intact after digestion, and thus spread to other areas while the elephants roam.

Black Rhino

Black rhinos were heavily poached between 1960 and 1995 — largely for their two horns. Their population consequently dropped by an astounding 98%, but they’ve made a large comeback since then due to conservation efforts. They are still critically endangered, and around 6,000 exist in the wild today in Kenya, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe.

Cross River Gorilla

A Cross River gorilla at the Limbe Wildlife Centre in Cameroon. Julie Langford / CC BY-SA 3.0

While they are very difficult to study given their habitat and wariness of humans, it’s estimated that between 200 and 300 Cross River gorillas are left in the wild. They live in the montane forests and rainforests of Cameroon and Nigeria in an area about twice the size of Rhode Island. This region has been increasingly encroached upon by humans, clearing their forest habitat for agriculture or raising livestock.

Javan Rhinos

Once found across southeast Asia, only one wild Javan rhino population of seventy-five individuals exists in Java, Indonesia inside the Ujung Kulon National Park. Their population has risen from about thirty in the 1960s, but they are still critically endangered and the most threatened of the five species of rhinos. Given their tiny population, their lack of genetic diversity through inbreeding is a cause for concern about their long-term survival. The invasive Arenga palm is a big reason for their downfall — it continues to threaten the rhinos as it overtakes the park and alters their historic habitat. Rising sea levels from climate change also threaten their geographic region, as does the threat of tsunamis and volcanos from Anak Krakatau nearby. Poaching for the rhino’s horns has historically been an issue as well and remains so.

Tigers

All subspecies of tigers — the Malayan, Sumatran, South China, Indochinese, Bengal, and Amur tigers — are either endangered or critically endangered. Three subspecies of tigers are already extinct. The South China Tiger is the most critically endangered of all. With no sightings in the last thirty years, it’s considered extinct in the wild, although 150 remain in captivity. Malayan tigers have an even smaller population, with only 80-120 mature individuals remaining in the wild in the forests of Malaysia. Sumatran tiger populations are of great concern as well — there are only about 400 left in the wild on the island of Sumatra: the only place left where elephants, orangutans, rhinos and tigers live together in the wild in a delicately balanced ecosystem. As apex predators, tigers play a crucial role in maintaining the balance of ecosystems. Currently, only 4,500 total individuals remain in the wild.

Hawksbill Turtle

One of only seven species of marine turtles, the hawksbill turtle is critically endangered. Since the 1990s, 80% of its population has been lost, leaving only between 20,000 and 23,000 in all of the world’s major oceans. Hawksbills are often bycatch in large-scale fishing operations, and are poached for their beautiful shells (known as “tortoise shells”) to make jewelry and other valuables — the IUCN estimates that millions have been killed within the last hundred years for their shells. Habitat destruction is another key factor. Their nesting grounds are heavily influenced by coastal development, and climate change is impacting the coral reefs that they feed on. These turtles are very important to the functioning of marine ecosystems, especially maintaining the health of seagrass beds and coral reefs.

Vaquita

This small porpoise only lives in the Gulf of California off of Mexico. The vaquita is critically endangered — but more than that, it’s the world’s rarest marine mammal and most endangered cetacean. Currently, only ten individuals remain. These creatures are highly susceptible to entanglement in the gillnets used to fish shrimp and finfish, and it’s still a victim of bycatch fishing for totoaba, although it’s illegal.

Kākāpō

The kākāpō is a fascinating nocturnal, flightless parrot native to New Zealand, and it almost went extinct. Habitat loss and the introduction of invasive species by European settlers like rats, stoats and cats — which were especially detrimental, given that the bird doesn’t fly and hadn’t adapted to mammalian predators — were major drivers of its population decline. Only about 250 are alive today, according to New Zealand’s Department of Conservation, but the species has seen some growth in recent years thanks to the efforts of Kākāpō Recovery.

Plants

When we think of endangered species, we might think only of animals, but plants are also in danger of extinction. Similarly to captive animals, some plants exist only in cultivation now, like the Middlemist Red (the rarest flower on Earth), the Franklin Tree and the Wood’s Cycad. Among the many listed by the IUCN Red List, these are three of the most highly threatened plant species.

Western Underground Orchid (Rhizanthella johnstonii)

The species Rhizanthella johnstonii occurs in Western Australia. Fred Hort / Flickr / CC BY 2.0

This orchid is considered crucially endangered in its native Australia with only fifty remaining individual plants. It lives its whole life underground and relies on a specific kind of mycorrhizal fungus to survive. Habitat loss is a big reason for its decline, particularly for agriculture. Drought has impacted species that it depends upon for nutrients, as has the invasion of weeds and compaction of soil by humans, particularly when hunting for it.

Texas Prairie Dawn Flower

Texas prairie dawn flowers. Carolyn Fannon / Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center

Formerly known as Texas bitterweed, this plant was renamed by school children in an attempt to improve negative attitudes towards it during conservation efforts. Now dubbed the Texas prairie dawn flower, this extremely rare annual wildflower is only found in the Texas Gulf Coastal Plain in the Fort Bend, Gregg, Harris and Trinity counties of Texas. Harris County — the home of Houston — is rapidly developing and contributing to the destruction of the flower’s habitat.

Ceroxylon quindiuense (Quindio Wax Palm)

Colombia’s national tree, the Quindio Wax Palm, is native to the montane forests of the Andes in both Colombia and Ecuador. Its endangered status arose after deforestation and agriculture began encroaching upon its territory. The palms’ seedlings die in the hot sun or are eaten by other creatures, so they aren’t able to reproduce outside of a forest. Wax palm forests are important to the survival of the yellow-eared parrot, among other species.

Fungi

Even though we often can’t see them, fungi are a crucial component of our lives. They are in everything, from the water we drink, the ground under our feet and the air we breathe. According to National Geographic, about 168 mushrooms have been assessed as threatened worldwide.

White Ferula Mushroom

White ferula mushrooms. tripsis / Flickr / CC BY-SA 3.0

This extremely rare mushroom is only found north of the island of Sicily in an area of less than 100 square kilometers. Their critically endangered status is due largely to overharvesting — as a gourmet food item, two pounds of white ferula sells for fifty euros.

Why Should We Protect Endangered Species?

Once a species is gone from the Earth, there is no way of getting it back. Protecting natural biodiversity has benefits we can predict, and some that we can’t. No one creature exists in a vacuum, but is connected to a large, delicate web of all species. Losing one species has a great impact on the balance of that web, especially when we lose a “keystone” species that helps hold the whole system together.

Protection of Food Chains

Species depend upon one another to survive. Since one species is a source of food for another, losing one can be disastrous to countless others, sending a ripple of disturbance down the food chain. We can see examples of such “trophic cascades” — that cascading effect of species loss down the food chain — throughout history. From the late 1800s to the 1920s, wolves in Yellowstone National Park were hunted nearly to extinction. In response, the populations of elk and deer they once preyed upon exploded, and decimated aspens and other trees that held stream banks together and supported birds. Insect populations burgeoned without their avian predators. Wolves were listed as endangered in 1974 and their recovery was thus mandated under the ESA. After wolves were reintroduced in the park in the 1990s, these decimated food chains recovered. The loss of apex species — the largest predators at the top of the food chain — like Yellowstone’s wolves is especially harmful. Because they tend to live longer and reproduce at slower rates, it also takes longer to recover their populations.

Scientists warn that the loss of plant and animal species due to climate change could cause an “extinction domino effect” of “co-extinctions,” which occur when one species dies out because it depended on another, causing subsequent extinctions down the food chain. In the worst-case scenario, this could kill off all life on Earth, according to a recent study from Flinders University in 2018.

Maintaining Ecosystems and Ecosystem Services

Balanced ecosystems are important. They provide us with crucial ecosystem services like flood regulation, water purification and nutrient cycling, which won’t function as well without all native species. California sea otter populations, for example, dropped in the 19th century from unrestricted hunting. The otters used to eat purple sea urchins, which eat kelp. Now, urchin populations have grown in the absence of otter predators, meaning they consume more kelp. Kelp forests provide important ecosystem services — like protecting the coast from storm surges and absorbing climate-warming carbon dioxide — but are less successful as their population diminishes.

Pollinators also provide vital ecological benefits. Over the past several decades, pollinator populations have been declining in North America. As of 2020, seventy species of pollinators including bats, birds and insects are listed as threatened or endangered. An estimated 75% of leading food crops depend on pollinators to grow — our entire food system depends on them. About 300 species of fruit depend on bats to get pollinated, including mangos and bananas. All pollinators face different threats, like imported diseases, invasive species and shrinking habitats, especially if patches along their migration routes are too fragmented. Pesticides pose another significant danger to pollinators. These toxins impact reproduction or harm the health of bees during direct contact. Additionally, insects and other animals could be beneficial to farmers as biological controls to keep pests in check. If we lose these species, we will rely even more heavily on synthetic chemicals to replace this service.

Preservation of Knowledge

Plants and animals also provide us with resources, like materials and new types of medicine. They’ve helped us create anti-cancer agents, blood thinners, pain killers and antibiotics, including penicillin, which was derived from a fungus. In all, 50% of the 150 top prescribed medicines were originally derived from plants and animals. Biodiversity presents us with the opportunity for new ways of feeding and sustaining our growing population, but by losing species to extinction, we lose that opportunity to innovate.

Loss of Livelihood

Whale-watching tourists in the Pacific Ocean off Puerto Vallarta, Mexico on March 8, 2022. Troy Mai / Flickr

Biodiverse communities are a source of income for many communities. Taking fishing communities, for example; if the fish they depend on are overfished to extinction, these people won’t be able to make any money. Biodiversity also has recreational value, providing us with opportunities for watching species like whales and birds, hiking on trails full of natural beauty, and more. The wildlife tourism industry is a multi-billion dollar sector, and the loss of species means the loss of major aesthetic value in these places, meaning tourism-centric economies will suffer.

Takeaway

Endangered species protection is a complex and intersectional issue. Species become threatened or extinct in a lot of different ways, some more indirect than habitat loss or poaching. Thus, to meaningfully address extinction risks, we must also consider climate change, our food systems and agricultural practices, and pollution.

Legislation is one of our strongest tools in fighting extinction, with the Endangered Species Act being a highly successful example. The whooping crane is a famous success story: the tallest bird in North America suffered from loss of habitat and hunting. In 1941 when it was listed as endangered, there were only twenty-one individuals left in its population — but after being listed as endangered in 1970, it now has more than 500. Other influential pieces of legislation throughout history include the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act of 1940 and the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972.

The Endangered Species Act turns 50 years old in 2023, but it and other legislation that protects endangered species are constantly under threat. Under the Trump administration, the ESA was stripped of vital provisions, ultimately paving the way for development, oil and gas drilling, and mining in critical habitats of endangered species. Although the Biden administration has begun restoring protections under the Act, these actions remind us that legislation is a powerful tool in preventing harm to threatened species: one that can be taken away under leadership that neglects environmental conservation. To protect endangered species and their habitats, it’s crucial that we vote for individuals who prioritize legislation related to environmental protection and large-scale action against climate change.

The post Endangered Species 101: Everything You Need to Know appeared first on EcoWatch.