Quick Key Facts

- The largest wildlife corridor in the world — the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing over the Highway 101 freeway at Liberty Canyon, California — is currently being constructed, and is expected to be completed in 2025.

- It is estimated that one to two million motor vehicles get into collisions with large animals like deer in the U.S. each year.

- Wildlife-vehicle collisions make up nearly 20 percent of reported crashes in rural states like Wyoming.

- A 2018 Center for American Progress study found that just 12 percent of land in America had been conserved as protected areas like national parks and wildlife refuges.

- One of the largest collections of wildlife crossings in the U.S. stretches across 56 miles of Montana’s U.S. Highway 93 North, where there are 41 wildlife and fish crossings, including overpasses and underpasses with fencing to direct animals like deer, grizzly bears, elk and cougars to the safe passageways.

- The top 10 U.S. States most at risk for wildlife-vehicle collisions are West Virginia; Montana; Pennsylvania; South Dakota; Michigan; Wisconsin; Iowa; Mississippi; Minnesota and Wyoming.

- More than 24 million acres of natural lands were lost to human developments like cities, roads and farms in the contiguous 48 U.S. states from 2001 to 2017.

- The Florida Wildlife Corridor is composed of almost 17.7 million acres.

- Eighty percent or more of the habitat of about half of all endangered and threatened species is located on private lands.

- A collaboration between Canada and the U.S., the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative has a goal of protecting connected habitat along a 2,000-mile stretch of North America’s Rocky Mountains for wild species like black bears and pronghorns.

What Are ‘Wildlife Corridors’?

A wildlife corridor is a strip of native habitat — either natural or human-made — connecting two or more natural habitats that have been disrupted by highways, cities or dams.

Habitats of wild animals can span smaller areas like a riverbank or stretch thousands of miles across an entire continent. The routes they take to find food, water and mates are called natural wildlife corridors. Wildlife refuges are essential for maintaining these expanses that mammals, birds and fish need to complete their life cycles. This is especially true as humans increasingly encroach on their domains, bisecting and cutting off their natural corridors with roads and development.

When roads have already cut through habitats, disrupting natural ranges and creating barriers to migration, human-made corridors may be constructed to provide the opportunity for safe passage for wildlife. Large mammals like elk can travel hundreds of miles between their summer and winter ranges, and fence breaks called “elk jumps” allow them to enter the western boundary of Wyoming’s National Elk Refuge, but limit their ability to leap out of the protected area near highways.

Landowners living next to wildlife preserves can work with the preserves to help provide safe passage for migrating animals on the many stretches of private land that lie between the patchwork of public lands and wildlife refuges across the country.

Why Are Wildlife Corridors Important?

The wildlife who share our planet with us have had their habitats systematically destroyed and overtaken by human development. Their natural ranges often span much larger areas than national parks, state parks or wildlife preserves can provide. Some mammals like caribou, wolves, birds, salmon and pumas travel hundreds or even thousands of miles throughout their lives, and maintaining safe, consistent pathways for them to migrate has become increasingly rare and difficult.

Wildlife corridors provide the space animals need to migrate to find food and water and reproduce so that they can thrive in their natural environments.

Types of Wildlife Corridors

Natural Wildlife Corridors

Natural wildlife corridors are strips of land that act as pathways for animals to travel between areas of fragmented habitat. These natural avenues offer refuge for traveling species and can increase their survival rates by providing access to food sources, as well as important escape cover or shelter.

The corridors can be established and developed through the cultivation of natural vegetation such as trees, shrubs or other herbaceous cover next to a stream or as a roadside buffer. No matter what the corridor is made of, its purpose is to provide safe passage so that wildlife may be able to access larger surrounding areas of habitat.

The types of habitat the corridor may be connecting can include wetlands, grasslands, fields, woods or other types of open terrain. The corridor should be at least 50 feet to 200 feet wide in order to provide a spacious enough lane for animals to travel, nest, find food or take cover.

Some of the species that will use wildlife corridors to move between larger areas of habitat include fox, deer, turtles, reptiles and raccoon. Species that use field buffers and corridors to nest and forage include turkeys, pheasant, quail, songbirds, cottontail rabbits and insects. The insects that use field borders are an essential food source for many of these animals.

Human-Made Wildlife Corridors

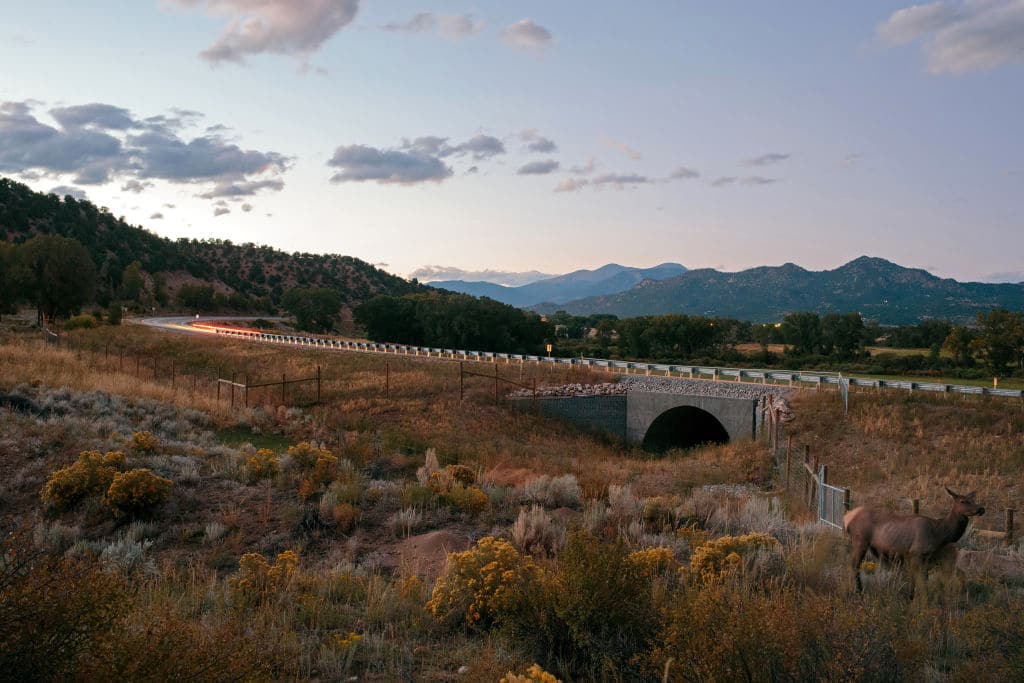

Human-made wildlife corridors are most commonly those that are built as overpasses or underpasses to provide a passageway for animals who need to cross busy roads in order to access their natural habitat or to migrate within their range. Typically, animals using human-made crossings have had their habitat diminished or destroyed by agricultural, housing or commercial developments.

The Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing over Highway 101 in California is an example of the complexity of natural habitats and the human-made wildlife corridors that try to emulate them. The crossing will be covered with soil and an acre of native plants that will allow it to blend in with the natural habitat on either side. The impressive corridor will be equipped with sound walls covered in vegetation to create a buffer for nocturnal animals against urban light and noise pollution. The green bridge will provide safe passage for animals like mountain lions, coyotes, reptiles and amphibians.

Which Species of Animals Use Wildlife Corridors?

Mammals

Large mammals can have extensive ranges, some spanning hundreds of miles and crossing many different types of terrain, including the human urban landscape.

Animals like elk, pronghorn and mule deer travel long distances between their wintering lowlands and the higher elevations where they spend their summers. As time has passed, new roads and developments have begun to crisscross and, in some cases, destroy the habitats of these majestic creatures.

Wildlife corridors help to soften the clash between wildlife habitat and human development by providing animals with a way to maneuver through urban landscapes and cross roads without encountering humans or their dangerous vehicles.

There are only two populations of endangered ocelots left in the U.S., most of their habitat having been destroyed by farming and residential development. This is why the 14 underpasses built by the Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge are essential to their survival in this country. Other animals caught on camera using them have been bobcats, possums, raccoons and coyotes. Two more wildlife bridges are slated for completion this year.

Amphibians & Reptiles

Roads have a high impact on amphibian and reptile species — including frogs, toads, turtles, salamanders, snakes and lizards — as they must cross them in order to get to essential foraging and breeding grounds. This can be especially true if roads bisect annual migration routes between habitats where the animals mate and hibernate.

These creatures move slowly and are often too small for drivers to spot and avoid in time. Lizards and snakes can also be drawn to paved roads, which usually absorb heat and retain it.

Types of aids for crossing roads and highways for reptiles and amphibians include underpasses, wildlife pipes, culverts or barrier fencing that guides amphibians in the direction of tunnels.

Some species like the California red-legged frog, the desert tortoise, the red diamond rattlesnake, the sierra newt and others have been highly ranked for being negatively impacted by roadways.

Birds

The long annual migrations of birds — sometimes thousands of miles — is well known. Many of them sleep during flight, resting half of their brains at a time, but they also land at known stopover sites to eat and sleep in a safe location, free of predators.

Wildlife refuges support all types of birds on their migration journeys — from waterfowl to songbirds — by being strategically spaced to provide havens for those migrating along the four main flyways that run north to south in the U.S. The refuges are a combination of state conservation areas and privately owned land. The four routes on the American Flyways cross the entire U.S. and include the Atlantic, Mississippi, Central and Pacific Flyways.

These havens for traveling birds are increasingly important as more and more wild bird habitats are swallowed up by agricultural land and urban and energy development.

Insects

Pollinators and other insects migrate, too, and they need a network of connected stopovers to rest and feed as they make their journeys.

Monarch butterflies travel as far as 3,000 miles between their northern breeding grounds and their overwintering sites in California and Mexico each fall and spring. On the southern route, they rest to feed on milkweed and other nectar-producing plants. In the northern parts of their territory, their larvae eat only milkweed, which is becoming harder to find due to increased use of pesticides, development and mowing. The planting of milkweed by private individuals and national wildlife refuges is essential to monarchs as they make their way along their ancient migration routes.

The “bee highway” in Oslo, Norway, was created in 2015 and includes meadows, rooftop gardens and potted flowering plants across the city to help the essential pollinators be able to breed, feed and migrate. Individuals and businesses worked along with the government to save the city’s bees and help them thrive through this unique wildlife corridor.

Fish

Wildlife corridors aren’t just for mammals and birds. Fish need to be able to swim freely through the rivers and streams that are part of their habitat.

There are approximately six million human-made fish barriers in the U.S., like dams and culverts, blocking the ability of fish to have clear passage through waterways to complete their natural life cycles.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has been replacing or removing some of these barriers, and nearly 4,500 miles of streams and more than 15,000 acres of wetlands have been reopened to fish passage, including many on wildlife refuges.

Benefits of Wildlife Corridors

Safe Passage

For millennia, North America was the undisturbed habitat of many majestic creatures who lived in harmony with the land and Indigenous Peoples. Wildlife corridors allow these animals to cross highways and roads safely as they migrate along ancient routes. This is especially important for species that travel long distances like elk, wolves, caribou and other species.

Prevent Habitat Fragmentation

Habitat fragmentation due primarily to agricultural, residential and commercial expansion has destroyed or cut off the habitats of many species, isolating them and leading some of them to become endangered. One important function of wildlife corridors is to connect these patchworks of wild domains so that species are able to access enough food, rest, find mates and reproduce. These passageways can also offer animals refuge if their habitat is shared with predators.

Help Plants Thrive

The protected environment of wildlife corridors can benefit a variety of native plant species, allowing them to flourish and provide nourishment and cover for wildlife passing through, nesting, giving birth or making long-term homes in corridors.

Prevent Vehicle-Wildlife Collisions

As many as two million large mammals are killed in wildlife-vehicle collisions each year, as well as many smaller animals. Wildlife crossings are essential for animals to be able to cross the increasing number of roadways blocking their movements. Crossings can be underpasses or bridges built especially for animals ranging from elephants to land crabs.

Minimize Wildlife-Human Interactions

By helping animals have access to adequate habitat, wildlife corridors can help keep them from feeling the need to venture into areas where humans live in search of food or to escape predators, thus minimizing wildlife-human interactions. This is important for both, as it keeps them safe from possible harms they could cause each other, and helps keep wildlife from becoming too familiar with humans and their food.

One study showed that the gut microbiome of wild black bears in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula became less diverse when they consumed human junk food.

Help Animals Have Access to Adequate Food and Water

The quest to find fresh water and food often leads animals on migrations of hundreds of miles. Different seasons bring different challenges for animals in meeting their basic needs, including drought, seasonal changes, flooding and human encroachment on their habitats.

Zebras, for instance, migrate hundreds of miles each year in order to find vegetation and water. The natural range for wolves can lead them to move as much as 30 miles each day in search of prey. In the U.S., elk have been migrating along the same routes for thousands of years.

Without wildlife corridors and adaptations to fencing on private land, many of these animals would not be able to find adequate food and water, greatly impairing their chance of survival in the wild.

Help Wildlife Species Find Mates and Promote Genetic Diversity

In order to maintain the genetic diversity that keeps populations healthy, animals need to be able to travel freely to find suitable mates. Metropolitan areas, roads, fencing and other barriers can block their movements. When animals are stuck in a particular habitat without freedom to roam, they are prone to inbreeding and unhealthy genetic isolation. This can leave them more susceptible to diseases and birth defects, lower their reproductive success and ultimately lead to population decline.

The expanded freedom of movement wildlife corridors give species promotes their genetic diversity, helping them to avoid the genetic disorders that can result from inbreeding.

Alleviate Wildlife Encroachment During Natural Disasters

If a natural disaster like a flood or a wildfire occurs, wildlife corridors can provide the escape route animals need to find safety rather than fleeing into a nearby town or city. This can help prevent human-animal conflicts, protecting both species.

Help Animals Adapt to Changes in Their Environment Due to Climate Change

As the planet warms, the vegetation or lack thereof that defines terrain either perishes or adjusts by adapting to the warmer temperatures or slowly shifting to higher elevations. Small animals may also shift their habitats with the changing climate.

As vegetation and prey species change or move, animals may need to explore new territory to find the sustenance they need.

During a drought, animals may need to go farther afield in search of fresh water. As snow lines move farther north, Canada lynx and other alpine species that rely on snowpack for making dens and to hunt may be forced to move northward or seek higher elevations.

Wildlife corridors can offer animals refuge and help them move safely from one pocket of habitat to another as they try and find ways to adapt to our rapidly warming world.

Promote Biodiversity

A 2019 study found that the linking together of habitats through wildlife corridors enhances biodiversity. The researchers discovered that, after 18 years, the habitats of South Carolina pine savanna that were connected with corridors had 14 percent higher levels of biodiversity, as well as an average of 24 more plant species, than the habitats that were not connected.

The support corridors offer pollinators means more pollen and seeds are spread, which strengthens the resilience of the ecosystem and boosts biodiversity. It also means more crops are pollinated, which in turn prevents soil erosion, sequesters carbon and helps keep flooding at bay.

Challenges Facing Wildlife Corridors

Funding

Wildlife corridors are desperately needed to mitigate the impacts of human development on wildlife populations, but one of the biggest obstacles to expanding the network of wildlife corridors is a lack of financial support.

For example, an Oregon State report from 2020 indicated that $22 to $35 billion was needed in “immediate” funding for statewide wildlife crossing projects. Funding is necessary not just for construction of wildlife corridors, but also for maintenance of existing structures.

Funding for conservation, including wildlife corridors, can come from local, state and federal agencies through legislation and appropriation, such as allocated funds from the sale of hunting and fishing licenses. Through the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, $350 million became available to Native American Tribes and state and local governments throughout the country to build wildlife corridors.

Research

Wildlife crossings and corridors must be tailored to the specific needs — such as types of vegetation and migration patterns — of the animals who inhabit the land they are being built upon. This requires studies to be conducted to make sure they are meeting the needs of particular species.

What Can We Do to Support Wildlife Corridors?

As a Society?

As a society, we can become more educated about ecosystems, biodiversity, conservation and the wildlife corridors that connect our protected areas. We can vote to elect officials who support the construction of wildlife bridges, underpasses and corridors, the restoration of wild spaces, rewilding and economic incentives for wildlife projects on private lands.

Rural landowners can turn parts of their property into wildlife corridors by partnering with public agencies that are working on corridor projects. They can modify their property with fencing that is conducive to wildlife migration and add buffer zones for animals. Areas that are not being used for agriculture can be planted with trees to create more habitat for a variety of species.

We can support nonprofit land trusts and work with them to make sure they are including wildlife corridors in their land management plans.

Urban planners can design wildlife crossings and make integrating them into municipal planning standard practice. One wildlife crossing can save as much as $443,000 each year by reducing animal-vehicle collisions.

Researchers can benefit society by studying the many climate benefits wildlife corridors provide, including providing shade to combat the effect of urban heat islands, carbon sequestration and minimizing the risk of flooding.

Another thing we can do as a society is to recognize Indigenous land rights and support the creation of wildlife corridors on Tribal lands. We can work with local and Indigenous communities, recognizing the cultural and spiritual connections they may have with the animals that migrate across their lands. By doing so we can gain valuable knowledge of the animals and their migratory patterns.

Animals have no political boundaries, so we can protect wildlife corridors that cross borders between countries by implementing international agreements to safeguard them, as well as work with global organizations that help coordinate corridor protections.

In Our Own Lives?

Depending on where you live, it may seem like wildlife corridors are far removed, but we can actually help them from our own backyards. Each green space is an opportunity to help create refuge, habitat and stepping stones for the wildlife who share our environment. You never know who will be passing through on their epic migrations to stop and rest, find food, make a new home and even bear young.

The more diversity of plant life we nurture in our gardens, the more animals will feel welcome to stop there — trees and nesting boxes for birds, grass for rabbits, flowering plants for pollinators, all free of pesticides and prohibitive fencing.

Think of your garden as a network, rather than an enclosed space. What animals are native to your area, and is there anything you could plant or modify that would help nurture and build the ecosystem you share? What are the wild spaces surrounding where you live like? Are they forest, orchard, grassland? These wild spaces are often where the animals that pass through your garden are headed to or coming from, so they can give you some clues as to what might help those animals on their journeys.

Other ways to help include learning more about wildlife corridors, volunteering with a local rewilding project or starting a pollinator garden or corridor in your neighborhood. Collaborate with neighbors on what native grass, flower and tree species would be most beneficial for animals in your region, stop or reduce mowing and either remove fencing or cut holes to allow animals like hedgehogs and rabbits to travel safely from garden to garden without having to veer onto sidewalks or roads.

Individuals can also speak up through public comments, sign petitions, attend community meetings and encourage government officials to support wildlife corridor projects.

By creating havens for biodiversity within areas where humans live, we can make transitions between landscapes more seamless, safe and nurturing for wildlife.

Takeaway

Human development, whether it be agricultural, residential or commercial, has replaced natural, balanced environments with concrete, steel and glass. Roads and highways have bisected ancient migration routes and cut off species from their known habitats, leaving them with no choice but to attempt to cross human-modified landscapes to find food, shelter and suitable mates.

Wildlife corridors are essential to provide safe passage to wildlife as they make the journeys that are part of their natural life cycle. Corridors have been shown to be effective, in some cases dramatically increasing the survival rates of species and the biodiversity of landscapes.

Humans must keep adding to the network of wildlife crossings, passageways and corridors, but also always be on the lookout for novel ways to restructure and rewild our environments. By doing so we can create environments that are more seamless with the natural landscape, as well as more inviting, secure and supportive of the animals with whom we share our planet.

The post Wildlife Corridors 101: Everything You Need to Know appeared first on EcoWatch.